This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The author contests older concepts of autonomy as either revolutionary or ineffective vis-à-vis the state. Looking at four prominent Latin American movements, she defines autonomy as 'the art of organising hope': a tool for indigenous and non-indigenous movements to prefigure alternative realities at a time when utopia can be no longer objected.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Politics of Autonomy in Latin America by A. Dinerstein in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Economic Policy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Theorising Autonomy

2

Meanings of Autonomy: Trajectories, Modes, Differences

Introduction: autonomy in Latin America

What is ‘autonomy’? The concept of autonomy has been historically the subject of enquiry by both scholar and activists alike but it has recently come under acute examination, generating worldwide debates about new social movements, power, politics, the state, policy and radical change. The reason is that for the past two decades the claim and practice of collective autonomy – in pursuit of self-determination, self-management, self-representation and self-government – independently from the state and institutionalised form of labour and party politics, have served new rural and urban movements to revitalised and push forward those legacies of other radical moments of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The principle of autonomy has also become a new ‘paradigm of resistance’ for indigenous movements (Burguete Cal y Mayor, 2010) relatively recently, and has been applied to the defence of self-government, indigenous legality and territoriality against new paradigms domination such as ‘multiculturalism’ (Burguete Cal y Mayor, 2010: 67). Multiculturalism emerged as a counter-paradigm to control indigenous resistance since the demand from the indigenous for the right to self-affirmation and self-determination together with the right to communal property of the land became part of the international agenda of the UN and other organisations, and new policy frameworks informed by the idea of diversity emerged to integrate this demand into the nation-state policies.

The term autonomy conjures up a multiplicity of resistances. Contemporary (struggles for) ‘autonomies’ (González, Burguete Cal y Mayor and Ortiz, 2010) bear diverse meanings throughout communities in different contexts (Mattiace, 2003: 187), as they encompass diverse histories, ‘trajectories’ and ‘self-defined collectivities’ (Cleaver, 2009: 25). Indigenous and non-indigenous, rural and urban movements, in the North and South have different conceptions and traditions of autonomy.

The indigenous movements’ demand for self-determination draws on ancestral practices and experiences against hundreds of years of appropriation and oppression. The claim for autonomy is associated with the indigenous cosmology of buen vivir, particularly from those in the Amazon and Andean regions. This covers specific meanings attributed to time, progress, human realisation, and the relationship between sociability, sustainability and nature, embraced by communal practices based on traditions, customs and cosmologies. Here, autonomy is both continuity and innovation (i.e., about the defence of tradition and customs against colonisation, appropriation and oppression) which in no way means the romantic return to the past but a reinterpretation of the past with ‘political imagination’ (Khasnabish, 2008). For non-indigenous movements, the roots of autonomy originated in the formation of anarchist resistance and mutual societies, cooperatives, Marxism consejista during the first decades of the twentieth century, and the work of the French group Socialism ou Barbarie (SoB), the Situacionist International at the end of 1950s, and Autonomia Operaia and the Quaderni Rossi in the 1960s (Albertani, 2009a). The autonomist movement became a political current within the left that embraces anti-authoritarian, libertarian and anti-bureaucratic struggles, particularly in the late 1960s, and during the 1970s mainly in Europe, with resonance in the South.

Leaving aside the disparities between indigenous and non-indigenous understandings of autonomy there are also significant contrasts between autonomous organising in the north and in the south (Ouviña, 2004). While in the North and with urban movements autonomy is associated with the struggle against the state and the abandonment of the idea of the state at the main locus for social emancipation, in the indigenous context, autonomy must be seen as the defence of territorial spaces of indigenous peoples and the recognition of their right to self-government by the state.

While autonomy in the north has been discussed as the anti-politics (Katsiaficas, 2006), as the subaltern vis-à-vis dominant classes and as a model of society (Modonesi, 2009, 2010; Thwaites Rey, 2004), as a temporal spatial strategy and interstitial strategy, and as a process of creation and everyday life revolution (Pickerill and Chatterton, 2006), indigenous struggles are seen as a tool for an insightful critique of modernity/capitalism, coloniality and the development paradigm (Escobar, 2010; Santos et al., 2008).

Refusal, non-conformity, civil disobedience and the reclaiming of spaces of freedom, democracy and self-determination against global capitalist social injustice in the north do not completely inform autonomous movements in the south, whose collective actions are directly connected to everyday concerns and vital needs usually under conditions of state repression, misery and poverty. Latin American movements have tended to led a ‘rebellion from the margins’ rather than be part of the mainstream network of social movements. They reject ‘politics as usual’ (Lazar, 2006: 185) and since they seriously suspect the state, they reject state power in principle, rather than seek to consolidate spaces for negotiation within it like in central democracies. Latin American social movements delivered what it can be seen as community policy (agrarian, labour, social, economic, heath, education) or policy from below which is source of resistance and tool for ameliorating poverty and unemployment. Many of their legitimate activities (like land or factory occupations) are considered illegal by the state. This might be partly explained by the bigger sense of ‘distance’ of the majority of the Latin American population from the state (Davis, 1999; Lazar and McNeish, 2006).

In Latin America, autonomous practices have been imagined, framed and organised in remarkably creative ways, coping with poverty, tackling the ‘absence’ of the state policy. This historical extrication was exacerbated by the crisis of the state that has been deeper in Latin America than in Europe –at least until recently (Slater, 1985: 9). Latin American social movements have contested excessive centralisation of decision-making power complemented with administrative inefficiency and the strong influence of informal political actors in the distribution of policy benefits and focus policies (Auyero, 2000), the state’s failure to provide adequate services, social security and welfare provision in the context of increasing scepticism about traditional political parties and leaders (Slater, 1985: 8). In addition to this, while it is generally accepted that the (relatively new) indigenous demand for self-affirmation and self-determination (autonomy) must be seen in the light of five hundred years of resistance in defence of indigenous cosmologies, traditions, habits and customs and, against colonial power, the implications of this for a conceptualisation of current forms of indigenous autonomies have not been entirely understood in the non-indigenous world.

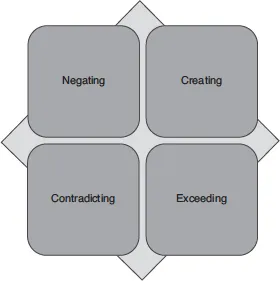

The four modes of autonomy

In the following sections, I review different treatments and trajectories of the concept of autonomy. My review is not exhaustive but it is organised around the above-mentioned four modes of the autonomous organising that are usually treated separately in the existing literature on autonomy (see Figure 2.1). I also expose the differences between indigenous and non-indigenous understanding of autonomy and the problems of universalising conceptualisations of autonomy produced in the North to explaining autonomy in Latin America

Negating: refusal to work, negative dialectics and disagreement

Negativity constitutes a key moment in social antagonism, that is, the ‘negative, denunciatory moment’ (Moylan, 1997: 111) of utopia as the instant of rejection of what it is. Since the 1960s, negativity is regarded as a chief component of autonomous struggles. Refusal to work, one of its forms of expression, materialized as an explicit workers’ motto in some sectors of the Italian working class in the 1960s and 1970s. This, according to Cleaver, intended to remind the left that ‘the working class has always struggled against work, from the time of primitive accumulation right on through to the present’ (in Cleaver and De Angelis, 1993). In Negri’s theory of communism refusal to work is an act directed to destroy surplus labour (Negri, 1991: 149). ‘Refusal to work’ was a form of resistance by autonomia operaia within the context of precarious work in Italy in the 1960s. In the late 1990s, the German group Krisis restored the idea of refusal to work in their ‘Manifesto against Work’ (Gruppe Krisis, 1999). There, they portray capitalist work as a coercive social principle through which exploitation and patriarchal society exists and call for the abolishment of work altogether. Refusal to work presents itself as an alternative option against both ‘socialism imagined either as state-planned economy to alleviate exploitation or as small scale production to remedy alienation’ (Weeks, 2011: 101).

Figure 2.1 The four modes of autonomy

But can refusal to work inform autonomy in the present? Lilley and Papadopoulos (2014) argue that in present forms of capitalism (bio-financial) refusal to work has become impossible because that the production of value impregnates every aspect of social life. In this sense, any political ‘autonomous’ alternative must deal with the contradiction entailed in the embeddedness of autonomous politics.

Holloway points to the contradictions brought about by refusal and negativity, for they inhabit working-class identity. He argues that ‘we do not struggle as working class, we struggle against being working class, and against being classified … there is nothing positive about being members of the working class, about being ordered, commanded, separated from our product and our process of production’ (Holloway, 2002c: 36–37, italics in the original). To him, the ‘working class’ is not constituted but permanently being constituted in a process that is based on the constant and violent separation of object from the subject. It is by engaging with the resistance that inhabits the concept and reality of the working class that we can anticipate not being the working class (Holloway, 2002c: 36–37).

This contradiction of being and not being the working class informs what Holloway and others regard as a current move from identity politics to anti-identitarian politics. It is argued that new forms of mobilisation and resistance reject identity politics on behalf of the formation of non-identities of resistance beyond state classifications. Flesher Fominaya (2010: 399) highlights that alter globalisation movements, for example, ‘reject ideological purity and fixed identities on principle’. To Seel and Plows, this ‘anti-identitarian orientation [constitutes the] “hallmark” of alter globalisation movements’ (cited in Fleyer Fominaya, 2010: 399). What this shows is the fluidity in identity formation and the falsehood of positive identities, which classify and pigeonhole people as well as close reality and possibilities.

The decision to explain this ‘anti-identitarian’ mode of autonomous organising has brought Theodor Adorno’s negative dialectics into the picture. Despite Adorno’s political pessimism, his negative dialectics is argued to engage with the open character of autonomous struggles; that is, an appreciation of the reality as open (Schwartzböck, 2008). How? To Adorno, there is no possibility of closure: ‘the negation of the negation would be another identity, a new delusion, a projection of consequential logic – and ultimately of the principle of subjectivity – upon the absolute’ (Adorno, 1995: 160). ‘Dialectics’ in Adorno’s words mean ‘to break the compulsion to achieve identity, and to break it by means of the energy stored up in that compulsion and congealed in its objectifications’ (Adorno, 1995: 157).

Negative dialectics is ‘the consistent sense of non-identity, of that which does not fit’ (Holloway, 2009a: 13). Matamoros Ponce contends that ‘Adorno ... places himself beyond the existing path, in the figure of negativity as a constellation of hope, that which is hidden in abnormality and resistance against the hierarchies of value and structuring homogeneity’ (Matamoros Ponce, 2009: 201). Negative dialectics means that movements’ praxis must be seen as ‘practical negativity’. Rather than embrace power or counter-power, negativity – according to Holloway – articulates ‘anti-power’. Our ‘doing’ – which in his critique of capital replaces the category of ‘work’ and designates what we do, as humans, as people – is anti-identitarian; it is fundamentally negative: ‘[t]he doing of the doers is deprived of social validation: we and our doing become invisible ... The flow of doing becomes an antagonistic process in which the doing of most is denied, in which the doing of most is appropriated by the few’ (Holloway, 2002a: 29–30). Doing (autonomy) is the negative movement that resists identity, that defies the forces that permanently transform our creativity and power to do into abstract labour and power over: ‘doing changes, negates an existing state of affairs’ (Holloway, 2002a: 23). The idea of resistance as practical negativity permits Holloway to make the distinction between negative and positive autonomism. While positive autonomism is classificatory and ‘flirts with progressive governments’, negative autonomism ‘pushes against and beyond all identities, part of the budding and flowering of useful creative-doing. The distinction matters politically’ (Holloway, 2009b: 99). Present autonomous resistance struggles are argued to be necessarily anti-identitarian.

The other significant form of conceiving autonomy and negativity is delineated by Rancière’s critique of neoliberal democracy. From a radical democracy tradition, Rancière defines politics not as a form of deliberation and consensus but as the possibility of disagreement: politics is an ‘exception to the principles according to which the gathering of people operates’ (Rancière, 2001: Thesis 6). Why is this important for an understanding of the negative mode of autonomy? Rancière defines politics (which is synonymous with democracy and autonomy) as disagreement. Politics breaks the logic of ‘consensus’ or the logic of what Rancière calls la police (what we normally call politics), which encompass, ‘the allocation of ways of doing, ways of being, and ways of saying’ (Rancière, 1999: 29) in politics or how things are. Politics entail dissensus beyond the conflict between opposed interests or different opinions on an issue. With disagreement, those who do not have a voice within la police – disrupt the established order. Events such as the Caracazo (1989), the Chiapas uprising (1994) or the popular uprising in Argentina (2001) called into question the foundations of la police. Through disagreement, movements opened a discussion about the meaning of politics altogether and the possibility of embracing alternative horizons.

Creating: self-instituting of society, self-valorisation and the common

While ‘negating’ is a key feature of autonomous organising, there is a second equally important and almost inseparable component of autonomous organising: creating. Castoriadis’ notion of autonomy -developed throughout the 1950s and 1960s in Socialisme ou Barbarie (SoB, 1947) is an example of the emphasis on this dimension of autonomy. Castoriadis articulated a virulent critique of both capitalism and the bureaucracy of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). SoB regarded autonomy and the self-organisation of the proletariat not only as a source of emancipation, but also as a tool to fight against communist parties’ and trade unions’ bureaucratic power (Blanchard, 2009). SoB’s treatment of autonomy was a weapon against state socialism. The group conceptualised socialism as the autonomy of the social, thus innovating the terms of the Marxist debate at the time. SoB described socialism as ‘nothing else than the conscious and perpetual activity of the masses’ (Chaulieu/Castoriadis, 1955). In this version of Socialism, the experience of self-determination was crucially important. By referring to the Greek’s invention of politics, Castoriadis argues that ‘the creation of democracy and philosophy is truly the creation of a historical movement in the strong sense’ (Castoriadis, 1991: 160–161, italics in the original). The self-interrogation that inhabits autonomy ‘has bearing not on “facts” but on the social imaginary significations and their possible grounding. This is a moment of creation, and it ushers in a new type of society and a new type of individuals ... autonomy is a project’ (Castoriadis, 1991: 165, italics in the original). Autonomy in the wide sense, is a project that illuminates the ‘instituting power of society [and] in the narrow sense’ is ‘the lucid and deliberate activity whose object is the explicit institution of society ... and its working as ... legislation, jurisdiction, governm...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1Embracing the Other Side: An Introduction

- Part I Theorising Autonomy

- Part II Navigating Autonomy

- Part III Rethinking Autonomy

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index