eBook - ePub

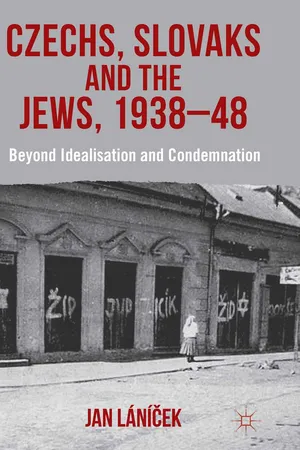

Czechs, Slovaks and the Jews, 1938-48

Beyond Idealisation and Condemnation

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Czechs, Slovaks and the Jews, 1938-48

Beyond Idealisation and Condemnation

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Covering the period between the Munich Agreement and the Communist Coup in February 1948, this groundbreaking work offers a novel, provocative analysis of the political activities and plans of the Czechoslovak exiles during and after the war years, and of the implementation of the plans in liberated Czechoslovakia after 1945.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Czechs, Slovaks and the Jews, 1938-48 by J. Lánicek,Kenneth A. Loparo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Exiles and the Situation in Nazi Europe

On 13 December 1938, the newly appointed Prime Minister of the Second Czechoslovak Republic, Rudolf Beran, presented the programme of his government to the National Assembly. The document reflected the changed nature of life in post-Munich Czechoslovakia, with the perceived need to find a modus vivendi with the neighbouring German Reich, now the indisputable ruler in Central Europe. In his address, Beran declared that the new government would ‘solve the Jewish question’ in Czechoslovakia. He added that the state’s attitude towards Jews, who had been settled in Czechoslovakia for a long time and had a positive attitude to the needs of the state and of its nation, would ‘not be hostile’.1 The programme was vague about what solving the Jewish question might mean and Beran’s words are unlikely to have been perceived as a threat to those Jews who had been living in Czechoslovakia for decades. Yet it clearly reflected the changed environment of post-Masaryk Czechoslovakia, with its growing right-wing and authoritarian sentiments of exclusion towards any entity perceived as foreign to the interests of the nation, as identified by the ruling right-wing establishment.2 The Second Republic lasted less than six months. Nevertheless its existence witnessed gradual exclusion of the Jews from Czech and Slovak societies. Additionally, following Nazi precepts, racial anti-Semitism was partly introduced, with limits set on Jewish employment in certain professions, like doctors or lawyers. Furthermore, revision of the citizenship of recently settled Jews was planned and the Slovak autonomous government even conducted deportations of several thousand Jews across the new border to Hungary. (In November 1938, Hungary annexed Southern Slovakia.)3 However, the efforts of the Beran government in the Czech lands, increasingly under the influence of the Third Reich, were short-lived. On 15 March 1939 Nazi Germany occupied Bohemia and Moravia, with Slovakia declaring its independence one day earlier. Czechoslovakia, as a state, ceased to exist, and the Czech lands were transformed into the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia.

Historiography of the Holocaust is in agreement that ordinary Czechs treated the Jews in the Protectorate decently.4 People expressed their solidarity with the suffering Jews and also extended basic assistance to their plight. Despite this, relatively few Jews survived in hiding in the Protectorate,5 but the explanation for this can largely be put down to geographical, demographic and political factors. It cannot be ascribed to any extensive Czech collaboration with the Nazis. Supporting this theory, Protectorate Sicherheitsdienst (SD) situational reports suggest that at some point during 1941, the Czech attitude towards the Jews became a serious problem for the occupation authorities.6 This assessment by the Nazi security apparatus appears especially to fit with events in the autumn of 1941 at the time of the branding of Jews with the Star of David (Illustration 1), the arrival in Prague of Reinhard Heydrich, as the Deputy Reichsprotektor, and preparations for deportations to the east.7 These accounts notwithstanding, there was a long history of anti-Semitism in the historical lands of Bohemia and Moravia. Besides the traditional Catholic sources of anti-Semitism, or anti-Judaism, economic and social tensions can be documented throughout the centuries. Furthermore, a special variety of anti-Semitism, developed in the nineteenth-century historical lands, perceived Jewish cultural and linguistic identification with Germans.8 These prejudices survived the fall of the Habsburg Empire, but they were not strongly articulated in the interwar period when Czechs dominated the newly founded Republic. Although the collapse of the Republic in 1938 caused their revival, the occupation of Bohemia and Moravia appears to have changed this trend, by revealing to the Czechs the real culprit of the national catastrophe.9 Indeed the crude Czech anti-Semitic circles who actively collaborated with the Nazi authorities did not receive significant overt support among ordinary Czechs.10 Although the Czech fascist groups, for example, The Banner (Vlajka), tried to stir anti-Jewish violence in the streets of Czech towns during 1939, Czech society at large never took part.11 The German authorities understood the limited support Czech fascists had in the society and used them only as a threat to the Protectorate government, as proof that they had other forces in case the ministers did not cooperate.12 Notwithstanding this limited support for Czech fascists, Benjamin Frommer suggests, documenting the complexity of the situation in occupied countries, that the Czech fascist press provided ordinary Czechs with an opportunity to denounce each other anonymously for their contacts with Jews. In this manner the fascists enabled Czechs to denounce their neighbours without having to contact the terrifying Nazi authorities and thus contribute to the ‘Final Solution’ in Bohemia and Moravia. As Frommer argues, the impact of the collaborators’ activities should not be marginalised.13

The second Protectorate government of General Alois Eliáš (April 1939–September 1941) is frequently praised for its alleged opposition to the implementation of strict Nuremberg Laws in the Protectorate in 1939.14 The definition of a Jew, as proposed by the government, was more lenient than the final law adopted by Konstantin von Neurath, the Reichsprotektor. Yet, the attitude of the Protectorate government was driven, at least partially, by their concerns that a wider definition of a Jew would transfer too much property from Czech hands to the Germans. Any company with a Jew (as defined by the law) in its management was designated for Aryanisation. The struggle over the definition of a Jew was decided unilaterally by von Neurath himself on 21 June 1939, and the German version of the Nuremberg Laws was introduced in the Protectorate.15

During the following months and years the Protectorate administration developed further initiatives to limit the position of Jews in society.16 The National Solidarity (Národní souručenství), involving almost the whole adult population, was the only quasi-political organisation allowed in the Protectorate.17 In 1940, anti-Semitic activists gained the upper hand in its leadership and introduced ‘Jewish decrees’ regulating contact between its members and the Jews. The decrees caused indignation in Czech society, however, and most of them had to be repealed.18 This Czech involvement in Nazi anti-Jewish policies documents the complexity of the situation in the Protectorate in the first years of the occupation. Only Heydrich’s arrival in Prague on 27 September 1941 as Deputy Reichsprotektor and the beginning of deportations to the east in October 1941 finally moved all initiatives into the hands of the German administration.

During the war, information about unwavering Czech decency towards the Jews filled columns in the western press.19 However, in investigating the reasons for such behaviour among Czechs, Nazi officials in the Protectorate concluded that it was more a case of ‘our enemy is [Czechs’] friend’, than of any altruistic character.20 Indeed, an SD report from August 1942 stated that public support for the Jews, expressed for example during deportations, was perceived by the Czechs as a way to convey anti-German sentiments.21 Additionally, the Czechs were afraid that after the Jews it would be their turn. As a consequence, Miroslav Kárný argues, the ‘ever more evident link’ to ‘the “solution of the Czech question” had a [strong] impact’ on Czech sympathy with the Jews.22 Later in the war, SD and Gestapo reports presented a complex picture of Czech attitudes towards the Jews. The Gestapo frequently reported significant assistance offered by ordinary Czechs to Jews trying to avoid deportation.23 In contrast, the SD in late 1943 concluded that an increasing number of Czechs both appreciated the Germans cleansing the Protectorate of its Jewry and did not wish the Jews to return.24 The majority of Czechs were allegedly against the Jewish presence in Bohemia and Moravia and hoped that the Jews would not want to come back after the war.25 This report cannot be dismissed purely as German propaganda, especially when taking into account previous SD reports condemning Czechs for their sympathy towards persecuted Jews. Likewise, the SD later stated that it was only because of the changing military and political situation in Europe that some Czechs behaved in a friendlier manner towards the remaining Jews, and the German agency concluded that even those Czechs who resented Jews sought political advantage in anticipation of Allied victory and the Jewish return to Bohemia and Moravia.26 The Czech attitude towards the Jews was allegedly cold-hearted and only the German military defeats contributed to friendlier contacts between the two groups. In particular the change in Czechs’ behaviour, as documented by the SD between approximately 1942 and 1943, deserves our attention. The reports suggest the Czechs’ concerns about the eventual return of the Jews in the case of Allied victory in the war. People who opposed the Nazi deportations of the Jews could have resented the eventual restitution of the Jews after the war at the same time. The SD reports were prepared by criminal agencies following their own policies and the information cannot be taken at face-value. Yet these surveys were intended only for internal use and we can accept that they might portray the situation as it was perceived in order that adequate measures might be taken.

Illustration 1 Jews in the Protectorate were from 1 September 1941 branded with the Star of David (Prague, Old Jewish Cemetery), Jewish Museum in Prague Photo Archive (2268)

There is a lack of any comprehensive study that would analyse Czech attitudes towards Jews in the Protectorate, but available documents, whose provenance lies within Czechoslovak resistance circles, tend to confirm Nazi observations. Anti-Semitic prejudices can be traced among some of the resistance leaders and Czech intellectuals.27 For example, an article from the underground Přítomnost, published in March 1943, reveals strong anti-Jewish sentiments among Czech underground groups.28 A similar analysis was presented by Emil Sobota, a pre-war official in Beneš’s presidential office who was executed by the Nazis in April 1945. Although Sobota did not condemn Jews on racial grounds, he labelled groups of Jews as anti-social and anti-Czech.29 Brutal Nazi policies aroused Czech sympathy for the persecuted minority, but Aryanisation allegedly confirmed to the Czechs the disproportionate wealth owned by the Jews. Sobota emphasised that subsequent development would be dependent on a solution to the ‘Jewish question’ by the post-war administration and that only ‘social justice’ in terms of restitution by the Jews would eradicate anti-Semitism in Czechoslovakia. If handled differently, Sobota concluded, even stronger anti-Semitism would emerge.30 Overall, Sobota confirmed the previous observations, when he concluded that the majority of Czechs avoided direct involvement in Nazi anti-Jewish policy. Hence historians and contemporary observers predominantly assert that a majority of Czechs did not take part in the persecution of the Jews. Yet despite the positive appraisal in the historiography and the self-assuring notes by contemporary observers, there was a part of Czech society that joined the Nazi racial crusade and their impact on the policies of the Czechoslovak resistance needs to be acknowledged now.

In thrall to the Jews

In the September 1941 issue of Harper’s Magazine, Benjamin Akzin, a revisionist Zionist, published an article called ‘The Jewish Question after the War’.31 Akzin concluded that as there was no place for the Jews in post-war Europe, the only solution was their emigration to Palestine. Even more revealing were the arguments he used. He opened with remarks made by Jan Masaryk (the son of T. G. Masaryk) in early 1940. Masaryk, who later became the Czechoslovak exile Foreign Minister, had assured a public gathering in London that all Jewish émigrés would eventually come back with him to liberated Czechoslovakia (Illustration 2). This statement received wide publicity and was taken up by the German authorities who used it to win public support in the Protectorate by warning Czechs that thanks to the exiles, the Jews would come back and reclaim all their property. As a consequence, according to Akzin, ‘these liberal Czechs’, concerned about the response at home, began to search for a place that would accommodate most of the Jews living in t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Map: The partition of wartime Czechoslovakia

- Introduction

- 1 The Exiles and the Situation in Nazi Europe

- 2 The Meaning of Loyalty: The Exiles and the Jews, 1939–41

- 3 The Holocaust

- 4 The Jewish Minority and Post-War Czechoslovakia

- 5 Defending the Democratic ‘Myth’

- Conclusion: Beyond Idealisation and Condemnation

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index