This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This critical study of the literary magazines, underground newspapers, and small press publications that had an impact on Charles Bukowski's early career, draws on archives, privately held unpublished Bukowski work, and interviews to shed new light on the ways in which Bukowski became an icon in the alternative literary scene in the 1960s.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Charles Bukowski, King of the Underground by A. Debritto in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

C H A P T E R 1

“Who’s Big in the Littles”

AN OUTSIDER DOING HIS WORK

It is beyond question that small press editors and publishers were caught up in Bukowski’s writing disease. Their littles are a testament to that. But what exactly is meant by “littles”? Most definitions emphasize that the littles, also known as “literary magazines,” “littlemags,” “small press magazines,” “journals,” “big littles,” “little littles,” and other variations, are the breeding ground for new authors. The great majority of well-established writers started out in the littles: Faulkner, Frost, Sandburg, Eliot, Steinbeck, Caldwell, and many others were first published in them. Hemingway’s first story ever appeared in The Double Dealer in 1922. Bukowski was no exception and Story: The Magazine of the Short Story printed his first short story in 1944. Many of these authors would eventually become famous, but their work first appeared in the littles regularly. By definition, the littles seek unknown talents and give voice to the voiceless.

There are conflicting views as to the value of the literature published in the littles. Tom Montag, one of the most important authorities on the littles and the small press, believes that they print “the best new literature available” (282). Corrington, who reviewed several Bukowski books in the 1960s, argues that they foster significant talent, but editor Jay Robert Nash begs to differ: “The little magazines . . . [publish] totally unknown writers; as a result, much of the poetry . . . is ego-oriented” (30). By promoting unfamiliar, obscure authors, the littles tend to be more daring than the highbrow quarterlies. Since they are not subsidized, experimentation by new writers is welcome, whereas academic journals tend to print staid material by established authors, seldom, if ever, venturing into compromising territory. Editor-author Karl Shapiro told a revealing anecdote about his editorial stint in Poetry: “Paul Goodman once sent me a group of obscene poems . . . I couldn’t print these. You know, you couldn’t use ‘shit’ and ‘fuck’ in Poetry . . . back in the fifties it would have meant the suppression of the magazine” (Anania 207). Clearly, the fear of censorship or suspension prevented most quarterlies from publishing experimental or offending material.

Some critics assert that academic journals not only avoided unknown authors and new literary values, but they were also unenthusiastic about literature. Emerging authors, then, submitted to the littles since they were their only outlet for publication. Poet Curtis Zahn was not mistaken when he claimed that “the Littles are perhaps the last vestige of freedom of the press . . . The Littles—where nobody gets paid, and advertising is not needed—have a clear field” (32). Some of the littles were fortunate enough to print completely unknown authors who were ultimately successful, but a large number of the names published in the littles have been long forgotten.

Another defining feature of the littles is their limited circulation. Since most of them were financed by young editors, budgets were tight and the total number of copies printed per issue could be derisory. However, the exact number of copies printed to qualify a magazine as little is not clear: Pollak maintains that “any circulation figure that falls in-between 200 and 2000 copies per issue” indicates the little status of a magazine (“What” 71), while Dorbin claims that fewer than 500 copies sufficed for a magazine to be considered little. Nonetheless, there are exceptions to these figures. Poetry: A Magazine of Verse, with 5,500 copies per issue, was termed the “largest little magazine in the country” (Parishi 230). Similarly, some issues of Evergreen Review, one of the key little magazines of the late 1950s and the 1960s, exceeded the 100,000 figure. In the case of most littles with a small print run, it was a standard practice to send free copies to other magazines, which, in turn, mailed their free copies out to other periodicals. This common pattern of exchanging issues with one another helped increase circulation figures into the hundreds.

Given the restricted distribution of the littles, it is not surprising to learn that their readership was also limited. In 1970, Dorbin estimated that the poetry audience in the United States “consists of no more than four thousand people . . . It is likely half of these are poets” (“Little Mag” 17). Dorbin’s suspicions were accurate; most littles were basically read by other editors and writers, with the occasional teacher, librarian, and student completing the list. James Boyer May, publisher of Trace, argued that the small circulation of the littles confined them to “‘In’ groups and to liberal universities and libraries” (24). The lack of circulation and readership is definitely one of the intrinsic features of the littles. If they had larger press run figures and were widely distributed, then they could not be qualified as littles. Save very few cases, such as Poetry, littles remained little or they simply disappeared after a few issues.

Littles were indeed ephemeral by nature. T. S. Eliot believed that little magazines should have “short lives” (qtd. in Anania 199), probably meaning a year or two, a view shared by most experts in the field. Long-lived littles are often qualified—pejoratively so—as “institutions.” Their vitality and experimental nature tends to dwindle in time, becoming middle-of-the-road and unoriginal in their approach to literature—Poetry or Prairie Schooner are two illustrious, oft-cited cases. An analysis of any little magazine checklist shows that the vast majority of those periodicals disappear after the publication of the first or the second issue. There are notable exceptions, as shown in the appendix. The Wormwood Review was an excellent example of a little magazine that did not become big despite having published almost 150 issues over a 30-year span. Bukowski was in most Wormwood Review issues, but he also appeared in Spectroscope, Understatement, Outcry, Mummy, and other littles that came out once or twice only.

Lack of funds explains the ephemerality of the littles. Most of them were in constant financial trouble, and editors had to bring them out with their own money if they wanted to keep them afloat. It is usually said that putting together a little is a work of labor and love. Publishers were supposed to act as editors, typesetters, collators, proofreaders, distributors, and even printers, and they had to do so keeping in mind that their ventures would never be profitable. As a matter of fact, most studies about the littles show that they seldom broke even. Long-established small presses, such as December Press, would suffer huge financial losses after decades of operation printing both books and magazines. Literary magazines could not last without financial subvention from institutions or private hands.

The Committee of Small Magazine Editors and Publishers (COSMEP) was launched in 1968 with the aim of helping those literary magazines with no financial resources. Other institutions, such as the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) and the Coordinating Council of Literary Magazines (CCLM), included the littles in their programs as well. However, many editors and publishers believed it was wiser to stay away from government money. They felt that accepting grants could seriously undermine the rebellious spirit of the littles. Their main purpose, that of promoting unknown authors and new literature, would be engulfed by the Establishment they despised so much. Bukowski himself distrusted these institutions because he felt that they were not really helping those editors in need: “As per COSMEP I really have some doubts as to the validity of the whole thing. There is a tendency to backslap and honeycomb, which is weakening,” he said to editors Darlene Fife and Robert Head (Paley, August 13, 1973). By refusing to be subsidized, editors exalted the independent nature of the littles and their perpetual cycle of life and death. If some little magazines had to disappear due to lack of funds, many others would soon be born, brimming with vitality and literary energy.

Indeed, the littles published during the 1940–1969 period experienced a dramatic change in the mid-1960s—the so-called mimeo revolution—preceded by an important surge of independent publications in 1956–1959. This change was instrumental to Bukowski’s career as it literally multiplied his exposure in the small press and little magazine circles, apart from constituting his first major stepping stone to popularity (see appendix, graph A1). However, Bukowski had already appeared in the littles in the 1940s and 1950s. Discussing the literary context where he edged his way into success is essential to fully grasp his evolution in the alternative press.

During the 1940s and the 1950s, the American literary scene was the realm of the highbrow quarterlies. The most prestigious journals— Kenyon Review, Sewanee Review, or Southern Review, all of them subsidized by universities—were strongly influenced by The New Critics. During the late 1940s, the medieval and Renaissance cultures had a powerful impact on the “Berkeley Renaissance” group. It is not known whether Bukowski submitted to those journals, but his unpublished correspondence and some late poems show that he was particularly attracted to the critical articles featured in those periodicals, especially in the case of the Kenyon Review.

In the early 1950s, many editors of little magazines still believed in Modernism as a role model to be followed, and they constantly quoted T. S. Eliot or Ezra Pound to express their views concerning publishing. The Partisan Review, the Hudson Review, or Poetry were obvious examples of magazines still entrenched in the tradition, while emerging littles such as Circle, The Ark, Goad, Inferno, Origin, and Golden Goose were trying to break loose from those Modernist reins. Although Bukowski submitted to both Cid Corman’s Origin and The Ark, his work was not accepted, whereas Kenneth Patchen, Kenneth Rexroth, Paul Goodman, William Everson, e. e. cummings, William Carlos Williams, and Robert Duncan were all published in The Ark in 1947.

By the mid-1950s, it was evident that a huge change was imminent. Years later, Bukowski reminisced about this period thus: “It is difficult to say exactly when the Revolution began, but roughly I’d judge about 1955 . . . and the effect of it has reached into and over the sacred ivy walls and even out into the streets of Man” (“Introduction” 1). Quite possibly, Bukowski was thinking of the San Francisco Renaissance, which, although originally conceived by Kenneth Rexroth in the 1940s, became noticeably popular in October 1955 with the Six Gallery Reading, where Allen Ginsberg’s Howl was first read in public. Several Beat-related events took place in the following years, preceded by Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s City Lights bookstore opening in 1953: Howl and the first issue of the cult magazine Semina were published in 1956; Jack Kerouac’s On the Road and Evergreen Review were premiered in 1957; William Burroughs’s Naked Lunch, Beatitude, and Big Table came out in 1959.

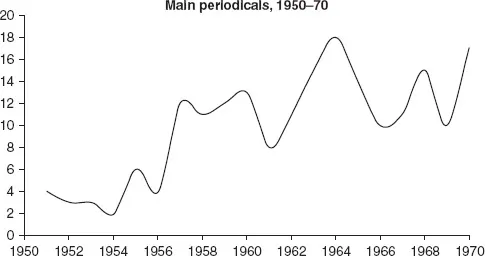

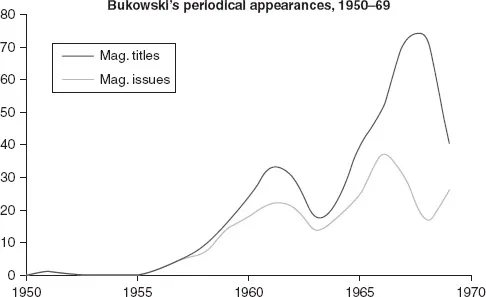

It was a fruitful period that heralded the literary explosion of the mid-1960s. Kostelanetz explained that “the years 1958–9 represented the beginning of a revival in American culture . . . Some of the potentially important new eclectic quarterlies made their debuts in that season” (26). The first major littles from this period were Tuli Kupferberg’s Birth (1957), John Wieners’s Measure (1957), Robert Bly’s The Fifties (1958), Leroi Jones’s Yugen (1958), Jack Spicer’s J (1959), John Bryan’s Renaissance (1961), and Leroi Jones and Diane di Prima’s Floating Bear (1961). Coincidentally enough, the outcrop of these key alternative publications took place when an increasing number of littles began to accept and publish Bukowski’s work, as illustrated in graphs 1.1 and 1.2.

Graph 1.1 This graph, based on the chronological timeline designed by Steven Clay and Rodney Phillips in A Secret Location on the Lower East Side, displays the total number of the main periodicals published from 1950 to 1970, clearly showing an upward pattern beginning ca. 1957, which would reach its peak in 1964–1965.

Graph 1.2 This graph, based on all the Bukowski bibliographies published to date and on several hundred periodicals located in American libraries, displays the chronological total number of magazine titles as well as the total number of magazine issues featuring Bukowski’s work from 1950 to 1969. As in graph 1.1, the increase in publications becomes evident in the late 1950s.

While the Modernism-influenced journals were being displaced by the emerging Beat publications, other literary movements were taking shape all across the United States or they unequivocally consolidated their relevance on the literary scene. Such was the case, on the one hand, of the Black Mountaineers, with Charles Olson and Robert Creeley as their main figures, and the Objectivists—also called second-generation Modernists—on the other, led by Louis Zukofsky and George Oppen. Their main literary publications were the already mentioned Origin (1951) and The Fifties (1958), as well as the Black Mountain Review (1954), Trobar (1960), El Corno Emplumado [The Plumed Horn] (1962), or Wild Dog (1963), among many others. The last two periodicals featured Bukowski’s contributions several times in the 1960s.

The creation of new schools was definitely encouraged during this period: The Deep Image school, including authors such as Jerome Rothenberg, David Antin, Clayton Eshleman, and Diane Wakoski, published Some/thing, Caterpillar, or Matter and other little magazines, where Bukowski’s poetry was printed. In New York, there were several waves of the commonly called New York Schools. The main figures of the different New York School generations were John Ashbery, Frank O’Hara, Ron Padgett, Dick Gallup, Joe Brainard, or Ted Berrigan, and the magazines that represented these schools were Folder (1953), White Dove Review (1959), Fuck You (1962), “C” (1963), or Angel Hair (1966). The late 1950s could be seen as a volcano about to erupt. All those new schools, groups, and periodicals were paving the way for a change that would release the literary scene from the overbearing control of the academic quarterlies and the last vestiges of Modernism.

Many critics believe that the literary revolution of...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- 1 “Who’s Big in the Littles”

- 2 The Insider Within

- 3 A Towering Giant with Small Feet

- 4 Stealing the Limelight

- 5 Curtain Calls

- Appendix

- Timeline

- Works Cited

- Index