This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The Transformation of Television Sport: New Methods, New Rules examines how developments in technology, broadcasting rights and regulation combine to determine what sport we see on television, where we can see it and what the final output looks and sounds like.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Transformation of Television Sport by M. Milne in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sozialwissenschaften & Landeskunde. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

SozialwissenschaftenSubtopic

Landeskunde1

Introduction

The rise of television sport

£5.14 billion: the value achieved in early 2015 by the Premier League as it sold domestic broadcasting rights in the UK for three years from 2016 to 2019. The Premier League is now the world’s second most lucrative sports league; the NFL, by accessing the larger US domestic market, leads the way as it generates £4.5 billion each season. Looking at the overall market in 2015, Pricewaterhouse Coopers estimates global sports business, including all revenue streams, was worth $145 billion (PwC, 2015). The value of Premier League broadcasting rights is particularly remarkable because, as recently as 1986, no one in the UK wanted to broadcast league football, not even highlights. Transformations of this scale and magnitude do not happen by accident.

Even with an increase in mobile and online viewing this is an era when, for most people, watching sport means turning on the television rather than visiting a stadium to see an event. In summer 2012 the sheer amount of television sport broadcast reached a new high mark including, in the UK, the EURO 2012 football tournament, tennis from Queens and Wimbledon, Bradley Wiggins’ success in the Tour de France, the London Olympics and the Paralympics. The ability of elite sport to attract very large audiences when broadcast on television, particularly on free-to-air television, underlines its continuing popularity. As a practical way for advertisers and sponsors to reach mass audiences, television sport has no equal. But scratch beneath the surface and a different picture emerges. Coverage of EURO 2012, the Tour de France, the London Olympics and Paralympics all came from federation-run broadcast operations aimed squarely at global audiences, leaving rights-holding broadcasters to concentrate on presentation for their local markets. In television sport things are not always as they first appear.

The transformation of television sport

Since the late 1980s the sector has been subject to unprecedented transformation as new methods and new rules have quietly been put in place. For all its prominence, television sport remains a surprisingly under-researched area. Like many, I have enjoyed watching television sport. But, as an executive producer, I have also worked on television sport in the UK, US and Japan, embracing sports as diverse as the NFL, NBA, MLB, Formula 1, World Rally Championships, Football Italia, Premier League, Bundesliga, Rugby Union and Sumo. Whilst my professional experience regularly placed me on the frontline, it was not enough for me to fully understand what has happened to television sport.

In terms of what we see, television sport consistently achieves remarkably high technical standards as it delivers captivating and sometimes spectacular engagement that can live long in our memory. But a nagging doubt remains: is this parade of slick technology and polished logistics a veneer that obscures our view of what is really happening? Thinking about what we see and where we see it, why has television sport in the UK changed beyond recognition in less than 25 years? Or, more generally, why does international sport coverage appear to have become more homogenised, even a bit bland? In an era that could have delivered unprecedented creativity, why are replication and inhibition recurrent themes? Even in a culture where hyperbole is the name of the game, is there really no place for any critical comment? This book is interested in who produces television sport, why it is produced the way it is and what the consequences might be.

Whilst there are several influential accounts – Holt (1989), Barnett (1990), Whannel (1992), Whitson (1998), Holt and Mason (2000), Boyle and Haynes (2000; 2004), Haynes (2005), Nauright and Schimmel (2005), Evens, Iosifidis and Smith (2013) – political economy interpretations of television sport remain at their best when painting the bigger picture. By focussing on major currents – for example, how the commodification of sport has accelerated (Mosco, 1996) as it is bound up in the processes of economic production and distribution (Mason, 1999) that deliver sport product on ever-increasing scales to international consumers (Nauright and Schimmel, 2005); the emergence of a sport-media-corporate axis (Falcous, 2005); or how sport is used as a battering ram to enter and take control of new markets (Herman and McChesney, 1997) – a demand side view has come to dominate discussion and has eclipsed a supply side interpretation. What is missing is an account of wider influences that trickle down and shape how television sports programmes are made, who makes them and what they finally look and sound like.

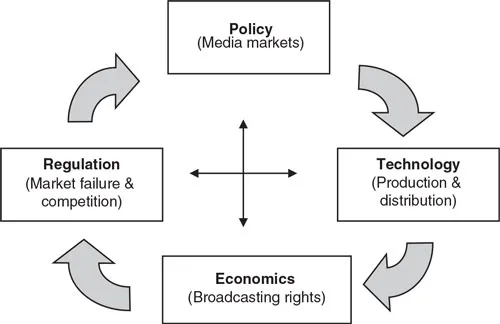

This book argues the transformation of television sport has been driven by a combination of interacting forces including broadcasting policy (media markets), technology, economics (broadcasting rights) and politics (media regulation). These forces mostly operate upstream and out of sight (i.e. before traditional production and distribution processes begin) and increasingly determine what sport we see, where we can see, and what the final output looks and sounds like.

In practice, developments in technology (encompassing transmission, production and distribution technology) are re-articulated via the broadcasting rights subsequently issued in the following cycle, typically every three years. The competition to acquire these broadcasting rights is mitigated (usually a further cycle behind) by industry regulators; these regulators and competition authorities echo the prevailing national or regional media policy.

A critical and often overlooked component is the interplay of technological development, broadcasting rights and regulation. As technological developments tend to move more quickly than rights or regulation, then regulators and competition authorities can be in a constant process of trying to catch up with developments. The book remains aware of (a) how economic markets work, (b) how market forces affect economic outcomes, and (c) how powerful actors attempt to manipulate market forces to advance their private interest (Gilpin, 2001:40).

Figure 1.1 Policy, technology, economics and regulation

Designed to complement the bigger picture usually provided by a political economy view, the objective here is to offer a convincing supply side perspective, one that tracks the impact of transformations downstream in the work of broadcasters, media providers, independent production companies as well as individual sports producers and directors. The book asks how television sport has changed, why it has changed so quickly and what these changes mean to practitioners and audiences.

The answers to three over-arching questions help to convey just how far the goalposts have been moved:

•Whilst sports and broadcasting systems in the US and UK started from diametrically opposed positions post-World War II, why have the similarities between them, including the adoption of a more overtly consumer-oriented approach in the UK, become the most noticeable features? How has the rise of global televised sports events and marketing-led television sport strategies accelerated this process?

•Transformations in television sports production since the mid-1990s have been driven by a combination of increasingly influential upstream forces including technology, sports broadcasting rights and regulation. How do these largely unseen pre-production processes influence what television sport looks and sounds like, where it can be seen and who can see it?

•What is the impact of pre-production processes on the downstream supply side, including (a) broadcasters (including who now provides sports media), (b) independent sports television production, and (c) the day-to-day work of sports producers and directors?

Specific consideration is also given to: 1) the remarkable growth in the volume and scope of television sport, 2) an unprecedented expansion in the number of channels and additional outlets, 3) fiercer competition between broadcasters and media providers to acquire elite sports broadcasting rights, including massive inflation in the cost of live broadcasting rights for the most popular sports, 4) the increasingly prescriptive demands on coverage required by federations, including the introduction of Production Manuals, 5) the introduction of federation-run host production operations and league-run channels that provide ‘approved’ coverage, 6) the increasing importance of presentation to local audiences by rights holding broadcasters and, 7) a growing emphasis on specialisation among sports producers and directors.

For Boyle and Haynes (2000:45), sport and television were ‘two great cultural forms which simply proved to be irresistible to each other’. As a result, sport has come to matter a great deal to big businesses and to the managers of increasingly commercial and global media industries. Of particular interest is how, in a short period, English football reformulated its structure, ethos and governance to become aligned with the interests of corporate investment and the managerial tenets of advertising, marketing and public relations (Falcous, 2005). In 1992 the Premier League was formed turning league football into a private good consumed for profit in a fully-fledged market economy. A new era of sports broadcasting had arrived in the UK.

As economics became the primary measure of value, the formation of the Premier League reflects the activities of other leagues and federations. Around the world leagues and federations have exercised their market power to extend control over their events and subsequent television output, so an increasingly prescriptive approach to television sports production becomes apparent. This includes additional conditions that are written into sports broadcasting rights as they are issued which creates a degree of conformity across output, despite the current phase being defined by an ever-increasing volume of content. From around 2005, leagues and federations began to produce their own ‘approved’ television coverage of their signature events, including the Olympics and World Cup Finals. Federation-controlled coverage is aimed at global audiences; this leaves rights-holding national broadcasters to provide more localised presentation for their own markets. The split between coverage and presentation is a significant development. Sharing the idea of a strictly controlled brand image, the Premier League now produces and distributes its own television channel for international distribution outside the UK. With international broadcasting rights for 2013–16 in the region of £2 billion, then revenues for the next rights, 2016–19, are expected to set new records. Today, leagues and federations have much more to say in determining what sport we see, where we can see it and what the final output looks and sounds like.

The political economy of television sport

Given the symbiotic relationship between media and sports organisations, Evens, Iosifidis and Smith (2013:4) describe a political economy approach that addresses how the behaviour of media organisations is shaped by the economic and political context in which they operate. The backdrop is neoliberalism and how this view is promoted via its policies of privatisation, liberalisation of markets, deregulation (and re-regulation that promotes free-market competition), corporatisation and the withdrawal of the state from many areas of social provision. Who gets what, when and how are questions that are seldom asked by economists but are central issues in a political economy interpretation.

With the increasing marketisation of broadcasting, and with sport (particularly in the UK) shedding many of its cultural and social connections in conditions where economic value has come to reign supreme, so a political economy interpretation can help reveal currents that are, on first inspection, more elusive. This approach is used to interpret upstream transformations and to track the shifting relationships (and behaviours) that increasingly define televised sport. In A Brief History of Neoliberalism, Harvey (2005) describes ‘accumulation through dispossession’ (2005:159) and how neoliberalisation has meant the ‘financialisation of everything’ (2005:33). Although directed at wider developments, these ideas are apposite when discussing the trajectory of television sport. However, this interpretation extends the vertical value chain for television sport upstream and downstream to include: (a) the pivotal role of sports leagues and federations in determining final television output, and (b) a micro-level analysis of downstream activities, or the day-to-day workplace methods that illustrate the ‘trickle down’ effect of wider transformations. This view is very closely connected to current industry practice.

A central issue in the book is the role of intellectual property rights and how control of sport broadcasting rights has become a vital activity of broadcasters and media providers, one that often defines their identity. Haynes (2005:5) points out that ‘to understand how copyright and other laws to protect intellectual property rights achieve their purpose, it is crucial to understand how different aspects of the media industry operate as technologies and businesses … ’ The book considers how sport has become so important to broadcasters and media providers. It updates understanding by examining the conditions that have transformed television sport and it offers new access to the relatively closed media world of television sport.

A thorough discussion of the transformation of television sport should address league and federation behaviour in more detail, including sports economics. This is a surprising omission from most political economy accounts. Sport is a sector where many economic rules appear to be inverted, particularly issues related to monopoly behaviour, including single entity co-operation (i.e. organising competitions) and joint venture co-operation (collective sale of broadcasting rights). The essence of sports economics is captured by Neale (1964:14): ‘It is clear that professional sports are a natural monopoly, marked by definite peculiarities both in the structure and in the functioning of their markets’. Considering several factors, including (a) elite athletic performance, (b) the shared experience that sport provides, (c) the uncertainty of outcome for live events, (d) lack of an adequate substitute in other programme forms, and (e) with demand from media providers to acquire rights for the most popular sports outstripping supply, then scarcity is said to exist. When scarcity exists ‘demand theory’ says that rationing devices must be chosen and the most prominent device is price, consequently the value of sports broadcasting rights rise as a result of competition from broadcasters and media providers. Scarcity, rationing and competition [for sports broadcasting rights] represent an ‘economic trinity’, Fort (2006:15).

Economically, the revenue side of professional sport changed forever with the willingness of advertisers to pay to access audiences that watch sports programming and the crucial importance of revenue from broadcasting rights was established, argues Fort (2006:53). How leagues and federations acquired significant market power, often via cartel control of broadcasting rights, is mapped.

A complementary interpretation would also benefit from extending discussion of media economics, including examination of the vertical value chain in television production. A fundamental issue for media providers is how to collect value from the audiences its programmes and schedules attract. For Picard (1989:17–19) media firms operate in a ‘dual product’ market. The two commodities generated are: 1) content (programmes produced or acquired and subsequently broadcast in recognisable schedules and; 2) the audiences that choose to watch. Commercial television networks can price and sell access to their audiences to advertisers and sponsors and the retention of audiences is critical to all broadcasters, including Public Service Broadcasters (PSBs). The ability of popular sports to consistently deliver audiences with more efficiency and demographic accuracy than many other genres is critical. Dominated by a small number of large firms television sports...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Foreword by Petros Iosifidis

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations and Acronyms

- 1. Introduction

- 2. History

- 3. Technology

- 4. Sports broadcasting rights

- 5. Regulation

- 6. Broadcasters and media providers

- 7. Independent sports television production

- 8. Conclusion

- References

- Index