eBook - ePub

The Political Economy of Climate Change Adaptation

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Political Economy of Climate Change Adaptation

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Drawing on concepts in political economy, political ecology, justice theory, and critical development studies, the authors offer the first comprehensive, systematic exploration of the ways in which adaptation projects can produce unintended, undesirable results.

This work is on the Global Policy: Next Generation list of six key books for understanding the politics of global climate change.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Political Economy of Climate Change Adaptation by Benjamin K. Sovacool,Björn-Ola Linnér in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & International Relations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction to the Political Economy of Climate Change Adaptation

1 Introduction

In 2007, Percy Schmeiser, an elderly farmer from Saskatchewan, Canada, unknowingly harvested a crop of canola that contained a herbicide- resistant gene patented by one of the world’s largest agricultural biotechnology companies, Monsanto.1 Schmeiser claimed that the canola had sprouted from seeds that had blown off passing trucks or spread from adjacent fields and mistakenly taken root on his farm – meaning he was not liable for patent infringement. Monsanto disagreed, and the case went all the way to the Canadian Supreme court, which reached a “bizarre” 5–4 decision that Schmeiser had infringed upon Monsanto’s patents, but was not liable for any damages.2

The implications of this anecdote are manifold and prophetic, extending well beyond an instance of a small-scale farmer, a “David,” losing to a large transnational corporation, a “Goliath.” It is an instance where Monsanto was in the process of actively modifying the genetic makeup of plants so that they were better adapted to the environment. It is an example of the commodification and corporatization of nature, where a company has patented and engineered a type of biodiversity. It is, lastly, a case where the profit motives of Monsanto pushed them to sue a farmer who likely only used their seeds by accident. In short, it is a case that raises a difficult question: is it appropriate to adapt or change a piece of nature, and to exclude others from its use, in order to make money or serve a particular interest and if so under what circumstances?

This book argues that in some cases of climate change adaptation – altering infrastructure, institutions, or ecosystems to respond to the impacts of climate change – profiteering, exclusion, or serving particular entrenched interests is neither appropriate nor effective. Notwithstanding the great promise that climate change adaptation efforts offer society, something might be going softly, silently awry with them. A survey of hundreds of studies of climate change adaptations implemented over the past decade reached a worrying conclusion: many projects were not helping the most vulnerable, and were instead strengthening established sectors that had already received large shares of adaptation funding.3 Another article warned that within adaptation projects, “deeply entrenched social institutions and norms may influence which group members will be able to have a voice and ultimately exercise rights.”4 Similarly, Biermann, Pattberg, and Zelli demonstrated how adaptation interventions are geared to serve particular interests, be it donor agencies or the agendas of particular companies.5 Adger hypothesized that “vulnerability to environmental change does not exist in isolation from the wider political economy of resource use” and that “vulnerability is driven by inadvertent or deliberate human action that reinforces self-interest and the distribution of power in addition to interacting with physical and ecological systems.”6

Notwithstanding these statements, little research has explored the systematic or structural aspects of the politics of adaptation head on, or the historical failures associated with adaptation projects. Instead, researchers have attempted to untangle separate threads of the topic sporadically. We group this prior research into seven strands of focus on the political economy aspects of adaptation:

1.Corruption in climate change adaptation and the politics of lobbying;7,8,9

2.Maladaptation, where adaptation projects unintentionally lower resilience or increase Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions;10,11

3.The winners and losers of climate change (e.g., who gets longer growing seasons compared to who suffers drought);12

4.The “double inequity” between responsibility for climate change (large industrialized emitters) and vulnerability to it (small developing economies);13

5.Sustainable adaptation, homing in on the consequences of adaptation policies and measures for other sustainable development goals;14

6.Tradeoffs between mitigation (reducing emissions) and adaptation (coping with consequences);15,16,17,18

7.Climate change and adaptation as a discourse19,20 – what Taylor calls an “array of discursive coordinates and institutional practices”21 – that serves to homogenize perspectives and diminish the autonomy of outsiders.

No research, as of yet, has systematically explored the tradeoffs within or between adaptation projects, or provided explanations for how the political economy of adaptation might operate. And so, two research questions emerge: Who are the winners and losers of adaptation projects? What underlying processes might affect the inequitable distribution of adaptation costs and benefits?

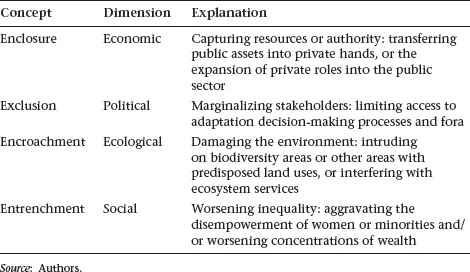

To provide an answer, this book documents the presence of four attributes to adaptation projects – processes we have termed enclosure, exclusion, encroachment, and entrenchment – cutting across the economic, political, ecological, and social dimensions summarized by Table 1.1. In a contribution to Nature Climate Change we pointed at eight other examples of these four processes.22 In this book, we find the four processes at work simultaneously in at least four case studies, two of them focusing on developing countries, two on developed countries. These cases involve the displacement of char communities in Bangladesh, the Dutch Delta Works in the Netherlands, Hurricane Katrina reconstruction efforts in the United States, and the politics of technology transfer and knowledge inequality within the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Our book concludes with a discussion of the broader implications of the political economy of adaptation for analysts, program managers, and climate researchers at large. In sum, the politics of adaptation must be taken into account so that projects can maximize their efficacy and avoid marginalizing those most vulnerable to the impacts of climate change.

Table 1.1 Conceptual typology of enclosure, exclusion, encroachment, and entrenchment

This introductory chapter begins by briefly familiarizing readers with the basics of climate change adaptation, defining its core elements, and offering a series of compelling reasons why it matters to society. It then summarizes four separate fields of inquiry – political economy, political ecology, justice theory, and critical development studies – that suggest we view adaptation not so much as a technical and economic process of coping with climate change, but as a deeply political and ethical process. The chapter then introduces the key theoretical framework of the book, namely the processes of enclosure, exclusion, encroachment, and entrenchment, and discusses the book’s primary research methods, before previewing the chapters to come.

Now, one quick, central caveat before we embark upon our textual odyssey. Before we give readers the wrong impression, neither of us is actually against human investments in climate change adaptation. We support adaptation projects and processes in both principle and practice. Many, if not most, projects probably have positive results. The four case studies examined here are a bit more complex, and may not produce net social benefits, but our main thesis is not that adaptation ought to be rejected. On the contrary. Instead, we argue that adaptation analysts and advocates need to become more cognizant of some of the potential downsides to adaptation, and take political economy into account to ensure that projects are freely decided upon, benefits fairly distributed and thus ultimately more effective in creating resilience for those vulnerable to a changing climate.

2 The basics of adaptation

It is best to start with a few definitions.

2.1 Adaptation

The concept of adaptation was defined in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) Fourth Assessment Report as “adjustment in natural or human systems in response to actual or expected climatic stimuli or their effects, which moderates harm or exploits beneficial opportunities.”23 Adaptation is often contrasted with mitigation, which the report defines as “an anthropogenic intervention to reduce the anthropogenic forcing of the climate system; it includes strategies to reduce greenhouse gas sources and emissions and enhance greenhouse gas sinks.”24 Put in very simple terms, mitigation is avoiding climate change, whereas adaptation is coping with climate change, or as Brown and Sovacool put it, mitigation is “avoiding the unmanageable” whereas adaptation is “managing the unavoidable.”25 That is the simple version. In practice, adaptation can be understood in a variety of ways. Table 1.2 introduces a number of related, though differing, prominent definitions of adaptation.

Though these definitions tell us that adaptation involves how humans deal with climate change, they do not tell us how adaptation usually occurs. One way of categorizing adaptation projects or interventions is by sector. As Table 1.3 indicates, climate-proofing buildings is one critical infrastructural option, along with hardening seawalls and other seacoast structures against rises in sea level. Institutional options tend to focus on improving the governance or public management of climate-related risks, such as the creation of early warning systems for severe weather events. Community options focus on the vitality and well-being of people, and can include risk transfer or insurance measures addressing low-frequency, high-severity weather events such as once-in-100-year floods.26 Lastly, ecosystems and natural capital – forests, wetlands, crops – can be made more adaptive.

Adaptation can be either reactive, seeking to blunt impacts that have happened, or proactive in the sense that it strategically anticipates and strives to avoid the effects of future undesired changes. Adaptation interventions can also be classified by their underlying logic or type. Ahmed, Alam, and Rahman categorized adaptation measures into at least seven strategies.27 The first is to “bear losses,” which amounts to basically doing nothing. John Holden in the U...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 Introduction to the Political Economy of Climate Change Adaptation

- 2 Bamboo Thumping Bandits: The Political Economy of Climate Adaptation in Bangladesh

- 3 Degraded Seascapes: The Political Economy of the Dutch Delta Works

- 4 Bloated Bodies: The Political Economy of Hurricane Katrina Recovery

- 5 The Perils of Climate Diplomacy: The Political Economy of the UNFCCC

- 6 Principles and Best Practices for Climate Change Adaptation

- 7 Insights from Political Economy for Adaptation Policy and Practice

- Notes

- Index