![]()

CHAPTER 1

HOW BIOFUEL POLICIES USHERED IN THE NEW ERA OF HIGH AND VOLATILE GRAIN AND OILSEED PRICES

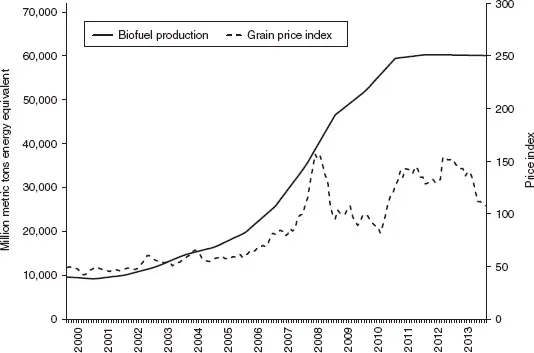

So far, we have emphasized the importance of the crop–biofuel–energy–crude oil price links, and the resulting two states of nature where corn prices can go no lower than when locked onto crude oil prices through ethanol and gasoline prices, and with tax credits.1 To illustrate the importance of price links and how quantity (sectoral supply/demand) shocks may not be the principal driving force in explaining food commodity price levels, consider Figure 1.1. Production of biofuels accelerated in mid-2000s and has now leveled off. Many commentators use that fact along with the pronounced volatility in grain prices in the meantime as a proof that biofuels are not the leading cause of high prices (e.g., Hamelinck 2013).

But ironically, in the time periods when grain prices decline in Figure 1.1, mandate premiums (ethanol price premiums above and beyond the tax credit) kick in so the relative impact of biofuel policies on corn prices is even higher. Another typical example is Baffes and Haniotis (2010, 12) who argue:

A small share of total output means a small impact on price; this is the conventional wisdom. Baffes and Haniotis (2010, 12) go on:

Figure 1.1 Grain prices versus biofuel production.

Source: British Petroleum (2013), World Bank (2014).

However, our interpretation of Figure 1.1 is quite different than that of the standard literature: so much of the impact of biofuel policies is summarized in price links; there is a lot less room for quantity shocks to matter in this new era. With these price linkages, in theory, the quantity of crops dedicated to biofuels can be irrelevant. Searchinger (2013) argues that the higher the price increase due to biofuels, the lower the supply response and, therefore, the lower the indirect land use change. However, such an analysis relies on traditional supply/demand analysis. Our analysis shows that it is very possible to have high price and land-use-change impacts simultaneously (or vice versa); again, this exemplifies the implications of our basic framework developed in this book that quantities may not matter as they did before the crop–biofuel price links were developed.

Before setting out to show how this crop–biofuel price link was formed, we first have to define biofuels and biofuel policies.

Defining Biofuels and Biofuel Policies

We first have to define what a biofuel is (see Box 1.1). For the purposes of this book, it is ethanol and biodiesel blended with gasoline and diesel, respectively, and used solely as transportation fuels.

Box 1.1 What is a biofuel?

Biofuels analyzed in this book are liquid fuels produced via various chemical processes from biological sources (plants or animals or “biomass”). Biofuels can be solid, liquid, or gaseous, but we focus on liquids that are substitutes to conventional fossil fuels (i.e., gasoline and diesel) and can be consumed either in their pure form or—most often—in blends with conventional fossil fuels. The biomass for the production of a biofuel is referred to as a biofuel feedstock. Currently, the bulk of ethanol (alcohol) is produced from agricultural crops such as corn, wheat, sugarcane, sugar beet, cassava, barley, and sorghum. Biodiesel (fatty acid ester) is made mostly from food crops such as soybean, rapeseed, and palm oil but also from recycled vegetable oils and animal fats.

Liquid biofuels are often classified into first-, second-, and third-generation biofuels. Biofuels from food crops and animal oil fats (those mentioned earlier) are first-generation whereas second-generation biofuels refer to ethanol from lignocellulose and organic wastes (e.g., miscanthus grass, corn-stover, tree material, waste wood, and paper); third-generation biofuels are from hydrogen produced either by gasification of lignocellulose or directly from microalgae. A fourth-generation biofuel would be one that is carbon negative (possible through genetic engineering of crops).

We focus on two main kinds of biofuels: ethanol and biodiesel. (As we discuss in Chapter 10, “renewable diesel” is made by a separate process than “biodiesel,” but for the purpose of this book, we lump them together). Ethanol is blended with gasoline and biodiesel is blended with diesel. Each feedstock typically produces only one type of biofuel, but some technologies have been developed to manufacture biodiesel from an ethanol feedstock—for example, corn oil extracted from the co-product of corn processed into ethanol is used for biodiesel production.

Common blends of ethanol include E10, E15, E85, and E100 (in Brazil) with 10, 15, 85, and 100 percent of ethanol in the final fuel mix, respectively. For biodiesel, these blends are B2, B5, and B20 (2, 5, and 20 percent of biodiesel).

One will come across a good number of papers describing how ethanol was first used at the turn of the last century in Henry Ford’s Model-T car but we argue throughout the book that this time is different (in terms of ethanol’s impact on agricultural markets) and, therefore, the historical use of ethanol is not relevant.

The US Energy Information Administration (EIA) (2013) projects biofuels will grow from 2 percent of transportation fuels to 4 percent (energy equivalent) in 2035 under current policies. Therefore, the current use of biofuels in total transportation fuels is very small and is to double in 20 years (but from a small base). Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)/Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) (2014) forecasts that biodiesel’s share of 25 percent in 2013 will stay the same in 2020. We will develop measures to assess the relative efficiency of biodiesel and ethanol in terms of price per mile achieved by consumers and their relative impacts on crop prices; we conclude that biodiesel is not nearly as inefficient as other economists claim, but the issue requires further research. International trade is a small share of production but is growing, and it is enough to link world biofuel prices; we will show in later chapters that this has important implications for crop price levels and volatility.

Although biofuel production and consumption are mostly concentrated in the United States, Europe, and Brazil, more than 60 countries have implemented biofuel policies. The other more important countries for biofuel production include Argentina, Canada, China, and India.

Next, we have to define what a biofuel policy is. Biofuel policies are a strange mix of rules, regulations, and market interventions that are sourced in environmental, energy, agricultural, and trade legislation. The policy toolkit is quite diverse, complex, and ever evolving and not always intended to impact biofuels and crop prices—the consequences were often unintended and neither understood nor anticipated. The main subsidy programs supporting the biofuels industry are twofold. First, market prices for biofuels are supported through blend mandates (a minimum percentage of total fuel requires biofuels; the subsidy conferred to biofuel producers from blend mandates that provide a guaranteed market for their product above free market levels). Second, biofuel consumption subsidies that by themselves raise the market price of a biofuel (tax credits in the United States and full or partial tax exemptions in all other countries that are fully applied to competing products—gasoline and diesel fuels).

The secondary yet important categories of biofuel policies include production subsidies, for both biofuels and feedstocks (e.g., for corn), including research and development (R&D) grants (promoting the development of biofuel projects or technologies), provided incentives for ethanol producers in the form of insured loans, tax write-offs, investment subsidies, price guarantees, and purchase agreements, and many federal and state “infrastructure” subsidies were created, such as subsidies for alternative vehicles and fueling stations. Export subsidies and import barriers—along with binary sustainability standards where biofuels from different feedstocks have different greenhouse gas (GHG) emission reductions relative to the fossil fuel they are assumed to replace—are also important ongoing policies. Relative excise fuel tax rates are also important (e.g., the European Union has diesel subsidies and both the European Union and the United States have higher tax exemptions for biodiesel). Perhaps the most important biofuel policies have been the environmental regulations that have impinged on requiring the increasing use of ethanol over other fuel additives (see Box 1.2).

Box 1.2 Do economists agree on what a biofuel policy is?

Although a thousand papers or more have been written on the economics of biofuel policies, surprisingly, economists cannot agree on what a biofuel policy is. Biofuel policies are different things to different people but, in reality, are a strange mix of rules, regulations, and market interventions that are sourced in environmental, energy, agricultural, and trade legislation. The policy toolkit is quite diverse and includes mandates, tax exemptions, subsidies for biofuels and their feedstocks, tax write-offs, investment subsidies, export subsidies, and import barriers. Moreover, there are binary sustainability standards where biofuels from different feedstocks have different GHG emission reductions relative to the fossil fuel they are assumed to replace. Policies are enacted at all levels of governments and have complex interaction effects, domestically and internationally (as it will be obvious as one reads through the book but see especially Chapter 12 for a more formal analysis of a few specific policy interaction effects).

As we have shown in this book so far, one has to recognize that the key influence of biofuel policies was to cause the link between crop and biofuel prices. The two key events for the corn–ethanol price link were the activation of the tax credit with high crude oil prices and the ban on methyl tertiary butyl ether (MTBE), a lower cost fuel additive that competes with ethanol. To understand the nuances of “biofuel policies,” just look at the US Clean Air Act regulations alone. These regulations can be construed as the key “environmental” policies leading to the crop–biofuel price links and the food commodity boom in 2007–2008 and thereafter.

The relevance of the Clean Air Act for food commodity prices began a long time ago with the ban on leaded gasoline that led to the adoption of MTBE. Then in the 1990s, reformulated gasoline (RFG) was mandated by Congress where more oxygenates like MTBE and ethanol were required to reduce local air pollution. Earlier, there was the 1984 federal legislation on leaking underground storage tanks (LUSTs) for gasoline that was not strictly enforced. LUSTs led to state bans on MTBE in the beginning of the 2000s. This was followed by the federal Renewable Fuel Standard in 2005 (to replace the RFG), the 2006 federal court decision not to grant immunity to lawsuits on using MTBE because of LUSTs (ethanol prices then reached their all-time peaks), the doubling of the original mandate legislated in 2005 in December 2007 (the current RFS), and, finally, the irreversible investments (due to the RFS) in gasoline production to use 10 percent ethanol as an octane enhancer (which has implications for the effects of removing a policy); see Chapter 12 for the effects of irreversible investments.

So what is the controversy? Some economists do not think any of these environmental regulations are public policies. According to Babcock (2013), only the 2005 and 2007 mandates are policies and all of the other regulations are “market forces.” The Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City (Kauffman 2012) correctly interprets Babcock’s views with a headline blaring “Markets, Not Mandates, Shape Ethanol Production”! But we argue that each of these Clean Air Act rules, regulations, and mandates is a biofuel “policy”; from one end (a ban on leaded gasoline) to the other end (where the RFS caused refiners to make irreversible investments). One should not pick and choose what a biofuel policy is and what it is not, just to conveniently make a point.

It is important to recognize that the first two categories of biofuel policies (in other words, tax credits/exemptions and mandates) do not, by themselves, discriminate against international trade. However, the other policies listed earlier do. For a good summary of all of these policies, see Chapter 1 in the High Level Panel of Experts ...