![]()

Part I

The Stars

![]()

Introduction

The Stars

When the Los Angeles Mirror-News, an afternoon tabloid spun off by the more respectable Los Angeles Times, headlined “Debbie Divorce Won’t Name Liz” on September 15, 1958, fans could read between the lines.1 Elizabeth Taylor, the world’s most beautiful femme fatale, had seduced pop singer Eddie Fisher while he was still married to wholesome girl-next-door Debbie Reynolds. As Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) stars who personified contrasting social types and cultural values, Liz was extravagant and Debbie parsimonious in their personal and, by implication, sexual lives. Such typecast femininity represented changing behavioral norms in a consumer society that was increasingly affluent yet remained nostalgic about its small-town past. While the growing middle class splurged on houses, cars, and appliances to realize the American Dream, a pleasurable lifestyle was becoming normative. But Americans did not wholeheartedly espouse materialistic values. As Cindy S. Aron argues, they valued work and discipline to secure their own well-being as well as that of society and, until the transformation of the postwar years, viewed idleness and leisure with suspicion; even then they had to repress a puritanical legacy of self-restraint in planning their summer vacations.2

Women have historically embodied ideological values, especially during periods of unsettling change and dislocation, and the social types in the postwar era were no exception. What is revealing is the enormous likability of girls next door like Esther Williams, Doris Day, and Debbie Reynolds. As wholesome, good-natured, and energetic pals who were prudent in their spending, they were approachable but not sexy. Such congenial girls evoked images of suburban ranch houses, manicured lawns, and backyard barbecues in homogeneous neighborhoods. A sign of upright small-town values transplanted in middle-class suburbia, they symbolized white flight from the blighted urban and industrial landscape. Suburbs did in fact rely on mortgage practices and zoning laws to confine racialized and lower-income peoples to housing in decaying cities. Wondrous sights like the White City at the Chicago Columbian Exposition in 1893 represented an enchanting vision, but the urban scene was usually suspect. A US Senate committee formed by Senator Estes Kefauver of Tennessee held hearings in 14 cities in 1950–1951 to disclose rampant municipal corruption and sordid organized crime. Sensational New York testimony was telecast to riveted audiences, and the film industry responded by producing several Kefauver policiers. Shocking revelations contrasted urban pollution with safe and secure suburbs as the site of the American Dream. The girl next door symbolized ethical Protestant values while sipping a soft drink in a drug store miles away from the crime scenes in Weegee’s lurid news photos. But she also embodied healthy fun under sunny California skies pierced by tropical palms and legitimized poolside leisure. As the million-dollar mermaid, Esther Williams was savvy enough to endorse stylish Cole of California swimsuits. Well before the end of the decade, however, the vivacious girl next door, whose ordinary qualities persuaded readers that they could indeed be friends, began to lose some of her charm. Publicity about curvy blonde bombshells and dark-haired sirens who had more exciting personalities was intriguing. Unlike the girl next door, these rival social types defined their feminine appeal with sexually overt behavior and embraced the pleasures of consumption. While bidding for artwork and shopping for haute couture in Paris, Elizabeth Taylor discovered hats and bought 50 or 60 of them.3 Such excess was essential to consumer capitalism and signified the abundance underlying a redefinition of personal identity, marital eroticism, and social relations.

Assessing the significance of the wholesome girl next door and her sexy rivals calls to mind Richard Dyer’s argument that the stars embodied ideological values in crisis. But even as these social types registered contradictions about the role of women in suburban America, they signified conventional white middle-class heterosexual norms.4 The very typicality of the stars enabled them to define how aspiring fans themselves should act. Consequently, the feminine social types including the girl next door, the fiery redhead, the refined lady, the fashionable gamine, the blonde bombshell, and the dark femme fatale represented a spectrum of more or less acceptable female behavior. But the behavioral norms set forth by typecasting in publicity stories that were usually less subject to resistant readings than films could still be ambiguous. Marilyn Monroe, for example, was both a waiflike orphan and a seductive centerfold at a time when an outmoded Production Code was being rewritten. As the decade progressed, Debbie Reynolds lost some of her fizzle as the effervescent girl next door, while sultry Liz Taylor anticipated a controversial sexual revolution. Analyzing the popularity of stars as social types thus reveals a great deal about the postwar construction of femininity that was idealized yet changing. Stars were all subject to wartime pinup reveries about their sexuality and to postwar sentiment about their maternity, but typecasting remained an industry practice until the end of the decade.

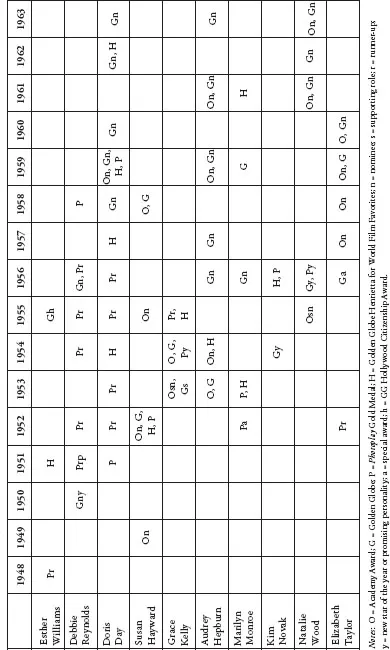

Since fan magazines were as important as films, if not more so, in constructing stardom, the first part of this book focuses on typecast stars publicized in Photoplay and extant issues of Motion Picture (1948–1963). Although personal taste influenced my selection, I chose stars who were interesting variations of the most popular feminine social types during these years. So I did not choose Janet Leigh, despite her being photographed with daughter Jamie Lee and married to heartthrob Tony Curtis, because she was not a distinct type. (Jamie Lee Curtis would herself become a star.) Since it marketed stars according to a formulaic publicity, Photoplay did portray Leigh as a “Cinderella in Pigtails” early in her career. With respect to a more objective baseline, I relied on trade paper reports about the earnings of popular box-office movies and on notable film industry awards. All the stars in this study, depending upon the metric, were listed among the top ten box-office attractions at some point in the decade. Using Variety’s annual top-grossing charts of the most profitable film releases, I computed box-office receipts for each star in successive years and for the decade as a whole (Table IS.1).5 Elizabeth Taylor was the biggest moneymaker, but Doris Day was more consistent in producing revenue across a span of a decade and a half. Unlike Taylor, Day was not constantly in the headlines trumpeting sex, shopping, and divorce. She exerted a wholesome appeal that was updated in sexy farces like Pillow Talk (1959). She was also a popular singer and rated as highly on Billboard charts as she was in movie exhibitor polls. Stars like Esther Williams, Grace Kelly, and Kim Novak were marquee names for a limited period of time. As the studio system declined, a star’s professional life could be cut even shorter, as was the case with Esther Williams in costly underwater spectacles. The rest of the stars on the chart including Marilyn Monroe reaped large receipts on a sporadic basis. Audrey Hepburn earned the least revenue during this period, but My Fair Lady, a profitable musical, was released in 1964. All the stars worked with studio contract directors and at least once with noted auteurs like John Huston, Elia Kazan, and Billy Wilder. Unsurprisingly, a star’s performance in an important production influenced her legacy. Kim Novak is today mostly remembered for her mysterious role in Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958), which recently displaced Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane (1941) at the top of Sight and Sound’s list of the greatest films ever made. Who besides cinéastes remembers her in The Eddy Duchin Story (1956), Jeanne Eagels (1957), or even Picnic (1955)? Star studies are to a significant extent influenced by auteurism so that matinee idols in top-grossing but forgotten films are today scarcely credited. After costarring with Gene Kelly in Singin’ in the Rain (1952)—later hailed as one of the best films ever made—Debbie Reynolds appeared in mediocre but moneymaking pictures that belied her importance as one of the biggest stars of the decade. A film like Tammy and the Bachelor (1957) was enormously popular among teens, reinforced sentimental gender relations, and spawned two sequels and a bestselling song. A focus on fan magazines as opposed to extant films thus provides an essential measure of the magnitude of stars who shone brilliantly in the past but then faded.

Table IS.1 Annual Variety Grosses

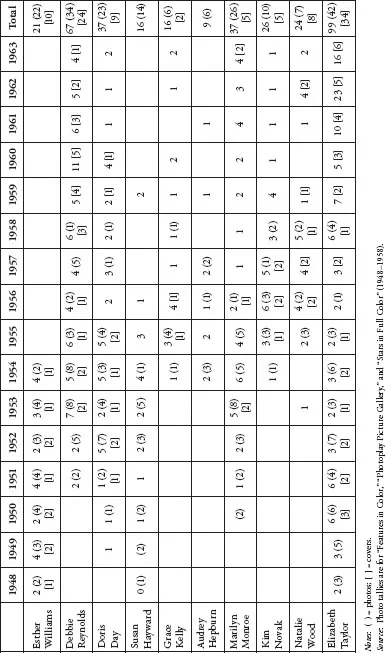

Awards that are still publicized today with great fanfare, especially to advertise and market films, provide additional data for assessing the brilliance of stars (Table IS.2). But what is being measured varies. The Hollywood Foreign Press Association, unlike the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, presents Golden Globes in two categories—dramatic films and musicals or comedies—so that it does not favor so-called prestige pictures. Stars like Esther Williams and Marilyn Monroe who performed in lighter genres were aware that critics did not take their work seriously. Scandal that dimmed a star’s aura influenced voting, especially in a decade when maintaining appearances was important and reinforced social convention. As a result of bad publicity about her brawling, Susan Hayward was nominated four times before she won as a murderer executed in California’s gas chamber in I Want to Live! (1958). Liz Taylor was nominated four years in a row at the end of the decade, but her scandalous role in Debbie Reynolds’s ugly marital breakup cost her votes. When she almost died of pneumonia in a London hospital, she gained enough sympathy to triumph in the part of a promiscuous woman in Butterfield 8 (1960). But she never won popularity contests like Photoplay’s Gold Medal Award or the Hollywood Foreign Press Association’s Henrietta Award for World Film Favorites. Such prizes were usually reserved for friendly and good-natured girls next door. Audrey Hepburn may have been the weakest box-office attraction during this period, but she won an Academy Award and a Golden Globe for her debut in Roman Holiday (1953). And she was nominated three more times by the Academy and four more times by the Hollywood Foreign Press Association. She also became the only actress, besides Shirley Booth, to win both an Oscar and a Tony in the same year. Winning the fewest awards were Esther Williams, a spectacle in Busby Berkeley productions with dialogue between numbers, and Kim Novak, an insecure actress groomed to succeed Rita Hayworth at Columbia.

The Photoplay Gold Medal Awards, which were presented in ceremonies photographed for newsreels and televised for viewers, were more accurate than the Academy Awards as a measure of fan reception. (Modern Screen also bestowed awards, but its issues are not all extant.) Susan Hayward, for example, won both the Gold Medal and the Golden Globe for portraying singer Jane Froman in With a Song in My Heart in 1952, but she lost the Oscar to Shirley Booth in Come Back, Little Sheba. Debbie Reynolds, a five-time runner-up for the Gold Medal, finally won in the midst of scandal as the wronged woman in 1959. During the decade, she was nominated once for a Golden Globe but never for an Academy Award. Attesting to consistent box-office power, Photoplay twice awarded the Gold Medal to Doris Day and named her as a runner-up four times. Day also won the Henrietta Award as a World Film Favorite four times. Additionally, Photoplay reported that Motion Picture Exhibitor acclaimed her as the most popular box-office actress of the decade.6 Day was an enduring favorite as the buoyant girl next door, but rival social types signifying serious drama won the prestigious acting awards. Susan Hayward received both the Gold Medal and Henrietta Award when she starred in a romantic musical like With a Song in My Heart, but her acclaimed performances as an alcoholic singer in I’ll Cry Tomorrow and a hard-luck floozy in I Want to Live! were less popular among fans. When Grace Kelly won an Oscar for The Country Girl in 1954, she played the drab role of an alcoholic’s wife and did not project her usual upper-class glamour. The Academy Award remained a coveted prize because it provided recognition that enhanced the exchange value of stars even in a decade that did not engage in nearly as much ballyhoo as the present.

Table IS.2 Annual Awards

What follows are biographical sketches of ten stars based on Photoplay and Motion Picture publicity about their private lives in an era of resurgent domestic ideology (Table IS.3). As stated above, the critical issue regarding these sources is not their authenticity and veracity but their value as gossip and rumor signifying social anxiety about the nature and role of women in postwar America. Photoplay was not even internally consistent with respect to spelling, accent marks, anecdotes, data, story titles, and authors. Uncovering the “truth” about the stars, moreover, can become an exercise in a Foucauldian will to knowledge about their identity and result in infinite regress. Despite a limited and inaccurate set of data derived from the fan magazines as a primary source, I cite only a few (more sensational) publications in constructing each profile. Anecdotal material that may be interesting or relevant was not included if it was not initially published in these sources. A focus on reconstructing fan magazines as an archival source also excludes a discussion of conventional star studies based on film performances. As Judith Mayne and Eric Smoodin argue, emphasis on “cinematic textuality in film studies” has been excessive.7 What this historical work provides are close readings of fan magazine stories about stars as feminine types in relation to mass consumption in postwar America. A vertical study, rather than a horizontal survey, is useful in illuminating the extent to which stardom conformed to the tenets of resurgent domestic ideology even as the stars themselves led private lives undermining such beliefs. When a concerned parent expressed dismay about her daughter being exposed to sensational tabloids, Photoplay’s editor Ann Higginbotham wrote a reassuring editorial. A later story about “sex and sin” in the film colony asserted that the “morals here are equal to or better than those in most places.”8 During an era of suburban togetherness, in sum, the fan magazines accented positive feminine role models in contented domestic scenes. Doris Day’s husband, Marty Melcher, costarred in her publicity because their stable married life together was essential to her cheerful girl-next-door image. Accumulating stories about the private lives of stars, which tend to be repetitious, invited my commentary. All ten profiles are the result of selecting and organizing data from innumerable pages to reconstruct a primary source, but the authorial voice that includes interpretive comments is mine.

Table IS.3 Annual Photoplay Stories Count

After ten profiles, a revealing conclusion based on parallel discourse that includes clip files, biographies, and autobiographies assesses Photoplay as a scree...