eBook - ePub

Money, Prices and Wages

Essays in Honour of Professor Nicholas Mayhew

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Money, Prices and Wages

Essays in Honour of Professor Nicholas Mayhew

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Nick Mayhew has made key contributions to fields as diverse as medieval European monetary history, numismatics, financial history, price and wage history, and macroeconomic history. These essays, in his honour, demonstrate the analytical power and chronological reach of the novel interdisciplinary approach he has nurtured in himself and others.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Money, Prices and Wages by M. Allen, D. Coffman, M. Allen,D. Coffman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Economic History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Coin Finds and the English Money Supply, c. 973–1544

Martin Allen

Introduction

One of Nicholas Mayhew’s greatest achievements has been his use of the various formulations of the Fisher Equation to investigate the connections between money supply, prices, wages and national income in England between the Domesday Book survey in 1086 and 1750 (Mayhew, 1995a; 1995b; 2004; 2013b, pp. 12–14, 35–8). In an important paper published in 1995 he analysed single finds of coins (as distinct from coin hoards), comparing them with estimates of the size of currency and GDP (Mayhew, 1995a, pp. 62–5). Mayhew brought together figures from Stuart Rigold’s pioneering study of finds from a hundred sites in England and Wales (Rigold, 1977), Michael Metcalf’s data for coins of c. 973–c. 1090 from various sources (Metcalf, 1980, pp. 22–31, 36–47), finds of c. 973–1180 published in the British Numismatic Journal in the 1980s, and coins of 1180–1544 Mayhew had himself recorded at the Ashmolean Museum. In 1997 Christopher Dyer analysed new data for finds of 1180–1544 from excavations of rural settlement sites and from the Warwickshire Sites and Monuments Record (Dyer, 1997, pp. 31–40), and Mayhew has revisited the subject in the light of finds recorded at the Ashmolean between 1992 and 2000 (Mayhew, 2002, pp. 18–21).

It is the purpose of this chapter to provide a fresh analysis of the evidence of finds for changes in the English monetary economy, based upon data for c. 973–1100 recently published by Rory Naismith (Naismith, 2013a) and the major new survey of finds of 1066–1544 from the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) and Corpus of Early Medieval Coins Finds (EMC) provided by the PhD dissertation of Richard Kelleher (Kelleher, 2012). Kelleher’s data include finds from Wales as well as from England, but the finds are predominantly English, with only 313 (1.9%) out of an impressive total of 16,802 being found in Wales (Kelleher, 2012, pp. 288, 315, 340). These new data have transformed our knowledge of the subject.

Mayhew’s analyses of finds of 1180–1544 broadly confirmed the chronological trends in Rigold’s data, supporting Rigold’s conclusion that finds were about 11 times more numerous c. 1300 than in the early Norman period (Rigold, 1977, p. 79; Mayhew, 1995a, pp. 62–5; 2002, pp. 18–21). Mayhew (1995a, p. 65) noted, however, the discrepancy between the coin find data and a 24-fold increase in estimates of the size of the English currency between 1086 and 1300, suggesting that coin loss might more closely reflect GDP (and the amount of work the currency had to perform) than the size of the currency, and hoping that further work might clarify this problem. Another issue addressed by Mayhew is that smaller coins may have been more likely to be lost and less likely to be found before modern times, so that any change in the denominational structure of the currency would have an effect upon the overall numbers of coins found. Mayhew (2002, pp. 6–7; 2004, pp. 82–3) noted that the finds of 1279–1351 in the Ashmolean data of 1992–2000 included fewer pence and more halfpence and farthings than might be expected from mint output data of this period. Consequently, the interpretation of Mayhew’s figures for the monetary values of the Ashmolean finds recorded in 1992–2000, which showed a fairly constant rate of 1.2d.–1.4d. per annum before and after 1279–1351, rising to 2.4d. in that period only (Mayhew, 2002, pp. 20–1), was far from straightforward. One final complication, which Mayhew was unable to address, is that hoards reveal that many coins of 1279–1351 survived in circulation after 1351, to be lost in subsequent periods, and this also applies to coins of later periods in Mayhew’s analysis (Rigold, 1977, pp. 62, 67; Archibald, 1988, pp. 286–93; Allen, 2005b, pp. 50–5, 62). The analysis of finds presented in this chapter will include an assessment of the survival of coins of the various denominations in circulation.

Numbers of finds

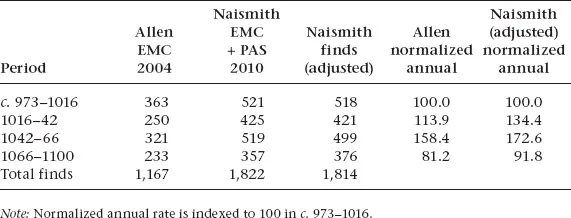

Rigold’s study began with Edgar’s reform of the English currency in about 973. Metcalf (1980, pp. 22–31, 36–47; 1998) has analysed finds of c. 973–c. 1090 in much greater detail than Rigold was able to do. In 1998 Metcalf published data from 588 single finds of English coins issued between c. 973 and c. 1090, and since that time the number of finds recorded has increased enormously, largely owing to the establishment of EMC and PAS in the late 1990s. I have analysed 2,039 single finds of c. 973–1180 from EMC (Allen, 2006b, pp. 499–500, 502), and Naismith’s recent analysis of data for c. 973–1100 from EMC and PAS has 1,852 finds (Naismith, 2013a). Naismith (2013b, pp. 56–8) has also used 1,329 finds of c. 973–1066 recorded by EMC and PAS in a study of the activity of the London mint. Table 1.1 compares my data with Naismith’s for c. 973–1100, including his adjustments of numbers of finds to take account of the survival of coins from one type into the periods of issue of later types. For the purposes of comparison the numbers of finds per year of issue are normalized to 100 in 1042–66.

Table 1.1 Single coin finds of c. 973–1100 in Allen and Naismith data

The two sets of data in Table 1.1 have broadly similar chronological trends, rising until 1042–66, and then falling by nearly a half in 1066–1100. Naismith (2013a, pp. 207–8, 220) has noted that the growth in the numbers of finds begins before Edgar’s reform of c. 973, and has suggested that it might be connected with an increase in supplies of imported silver from mines in the Harz mountains in the last third of the tenth century. Although Mayhew (1995a, p. 65) has cautioned that numbers of finds are probably related to monetary activity, which can be subject to change, Naismith (2013a, pp. 200–1) argues that prices and the intensity of coin use were probably relatively stable around 1000, with little effect upon numbers of coins found. The peaking of the finds in 1042–66 may be connected with the decline of large-scale movements of English coinage to Scandinavia in tribute and payments to mercenaries, starting in the 1030s and particularly evident from c. 1050, with a consequent increase in the numbers of coins remaining in circulation in England (Allen, 2006b, p. 500; Naismith, 2013a, pp. 210–11, 220; 2013b, pp. 57–8). The decline in the number of finds in 1066–1100 is consistent with Peter Spufford’s suggestion that European currency stocks contracted in the later eleventh century, because of a fall in the productivity of the silver mines in the Harz (Spufford, 1988, pp. 95–9; Naismith, 2013a, pp. 208, 220).

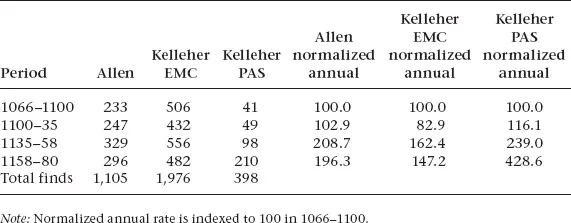

Kelleher’s data for 1066–1158, from EMC and PAS, are compared with mine in Table 1.2, indexing the numbers of finds at 100 in 1066–1100. The three sets of figures show an increase of about 100 per cent between 1100–35 and 1135–58, suggesting a revival in monetary activity, but they diverge after 1158, declining slightly in the EMC data while showing a nearly two-fold increase in PAS. The PAS data may provide a truer reflection of the numbers of coins found, because PAS records all finds of coins and artefacts in principle, whereas some finders reporting coins to EMC may not be aware that its period of coverage ends in 1180 rather than in 1158, resulting in under-reporting of coins of 1158–80. If it is accepted that the PAS data provide evidence of an increase in the currency and monetary activity in 1158–80, this would be consistent with the suggestion that increasing supplies of mined silver from Germany supported a substantial growth in the English currency from about 1180 or slightly earlier, in the 1170s (Harvey, 1973, pp. 25–8; 1976, 370–2, 375; Mayhew, 1984, pp. 166–8; Dawson and Mayhew, 1987, p. 115; Spufford, 1988, pp. 109–31; Allen, 2012, pp. 254–5).

Table 1.2 Single coin finds of 1066–1180 in Allen and Kelleher data

EMC ends with the termination of Henry II’s Cross-and-Crosslets (Tealby) coinage in 1180, and after that date the numbers of finds in Kelleher’s data from PAS greatly exceed the numbers recorded by Rigold in 1977 and Mayhew in 2002. Table 1.3 compares the three sets of data, indexing the number of finds per year of issue to 100 in 1279–1351, to aid the comparison. The periods in the table are those first used by Rigold, taking the reforms of the English coinage in 1247, 1279, 1351, 1412 and 1464 as the dividing points. All three sets of data peak in 1279–1351, but there are significant differences between the figures. It will be seen that Mayhew and Kelleher have considerably more finds per annum than Rigold in the two periods before 1279, in comparison with 1279–1351, and that the Kelleher data for 1247–79 greatly exceed Mayhew’s in 1247–79, almost equalling the annual rate of 1279–1351. All three sets of data show a substantial decline in annual rates after 1351, but this takes no account of the monetary values of the coins found or of the possibility that coins were lost after their periods of issue. These two factors will now be assessed using Kelleher’s data.

Coin denominations and the monetary values of finds

Mayhew’s suggestion that smaller coins are more likely to be lost and less likely to be retrieved at the time of loss than larger and more valuable coins (Mayhew, 2002, pp. 6–7; 2004, pp. 82–3) has been confirmed by an analysis of 1,000 modern coins found during walks in Melbourne, Australia in 2005–8, and by comparative data from England, the USA and Japan (Frazer and van der Touw, 2010, pp. 395–400; Newton, 2006, pp. 215–20). Consequently, the proportions of the denominations in the find data cannot be regarded as a direct measure of the proportions in the circulating currency, but they do provide evidence of changes in the denominational structure of the currency.

Table 1.3 Single coin finds of 1180–1544 in Rigold, Mayhew and Kelleher data

The denominations and values of the finds in Kelleher’s PAS data are summarized in Tables 1.4 and 1.5, using information from spreadsheets of the finds very generously provided by Dr Kelleher. The figures in Table 1.4 show very marked overall increases in the percentages of cut halfpence and farthings from 1100–35 to 1247–79. Kelleher (2012, pp. 71–6) connects this with the increasing commercialization of England and Wales in this period, and he notes higher percentages of cut fractions on urban sites than from rural areas before 1158, indicating a higher level of commercialization in urban areas. By 1247–79 the difference between urban and rural finds disappears, apparently indicating a more integrated monetary economy.

The trend towards larger percentages of fractional denominations comes to an abrupt halt in 1279, when Edward I’s reform of the English coinage replaced the cut fractions with an inadequate supply of round halfpence and farthings. Between 1281 and 1327 only 0.4 per cent of the output of the London and Canterbury mints was in halfpence and 5.3 per cent in farthings (Allen, 2004, pp. 43–4; 2012, pp. 353–4). From 1351 the recorded mint outputs in silver tend to be dominated by the groat (4d.) and halfgroat (2d.), although the indentures of the masters of the royal mints often attempted to specify that substantial stated proportions of the output should be devoted to the smaller denominations. The mint officials had no financial incentives to produce the smaller coins, and from the 1360s to the 1440s parliamentary petitions complain about shortages of small change (Allen, 2007). Kelleher’s data show the overall percentage of halfpence and farthings falling sharply from 61.3 per cent in 1247–79 to only 14.8 per cent in 1279–1351, and he notes that nearly half of the value of the finds of silver coins of 1351–1412 is provided by groats, increasing to over 50 per cent in 1412–64, while gold coins become a significant element in the data for the first time after 1351 (Kelleher, 2012, pp. 131–6).

Table 1.4 Percentages of denominations in Kelleher data from PAS

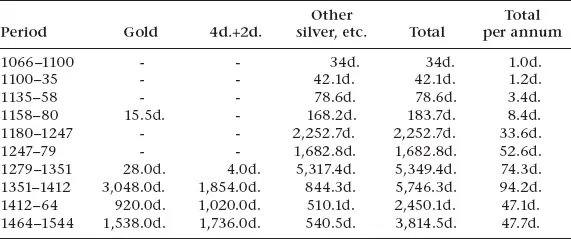

Table 1.5 Values of coin finds in Kelleher data from PAS

Table 1.5 summarizes the values of the gold and silver finds in Kelleher’s PAS data, dividing them into the three categories of gold, the larger silver denominations (groat and halfgroat), and other coins. English, Irish and Scottish coins have been assigned their nominal (face) values at t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- 1 Coin Finds and the English Money Supply, c. 973–1544

- 2 National Income in Domesday England

- 3 Modelling the Medieval Economy: Money, Prices and Income in England, 1263–1520

- 4 Prices from the Durham Obedientiary Account Rolls, 1278–1367

- 5 Credit, Crisis and the Money Supply, c. 1280–1330

- 6 Finance on the Frontier: Money and Credit in Northumberland, Westmorland, and Cumberland, in the Later Middle Ages

- 7 Money and Rural Credit in the Later Middle Ages Revisited

- 8 The Morality of Money in Late Medieval England

- 9 Labour Turnover and Wage Rates on the Demesnes of Durham Priory, 1370–1410

- 10 A Golden Age Rediscovered: Labourers’ Wages in the Fifteenth Century

- 11 Corn Prices, Corn Models and Corn Rents: What Can We Learn from the English Corn Returns?

- 12 London’s Market for Bullion and Specie in the Eighteenth Century: The Roles of the London Mint and the Bank of England in the Stabilization of Prices

- 13 Monetary Trends in the UK since 1870

- Publications of Nicholas Mayhew

- Bibliography

- Index