eBook - ePub

Understanding and Managing IT Outsourcing

A Partnership Approach

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Understanding and Managing IT Outsourcing explains and illustrates how uncertainty and trust interact with each other, and how an understanding of this interaction is critical to success in IT outsourcing. A partnership approach that is built on trust can be the determinant of success but this book explains in which particular outsourcing context this approach is likely to pay dividends.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Understanding and Managing IT Outsourcing by S. Datta,N. Oschlag-Michael in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business Strategy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

IT Outsourcing

Datta, Surja and Neil Oschlag-Michael. Understanding and Managing IT Outsourcing: A Partnership Approach. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015. DOI: 10.1057/9781137497321.0006.

The aim in this section is to provide an introduction to IT outsourcing and set the context for the issues of uncertainties, trust and partnerships, all of which are examined in detail in the subsequent chapters.

1.1 Introduction

Grover et al. (1996) provide a simple definition of IT outsourcing, namely the practice of turning over part or all of an organization’s information system functions to an external service provider. This definition addresses the issue of the terms IT outsourcing and information system outsourcing (ISO), being used interchangeably.

Given that outsourcing is often mistaken for offshoring, it is worth noting that offshoring, within the context of outsourcing, is when some or all of the service provided is delivered from a foreign location. In offshored outsourcing complexity of services increases, as does uncertainty and the need for management control and trust in the outsourcing relationship (Gottschalk and Solli-Saether, 2005).

IT outsourcing roots can be traced to the traditional time sharing and professional services of the 1960s and 1970s (Grover et al., 1996). The 1970s marked the beginning of the application package concept and the decline of processing services and the 1980s marked the arrival of low-cost minicomputers and PCs and focus shifted to IT-supported vertical integration during this decade (Kim et al., 2003). IT outsourcing has been widely publicized ever since Kodak’s landmark decision to outsource the bulk of their IT functions in the late 1980s (Willcocks and Lacity, 2009). In the early 1990s interest in outsourcing resurfaced with network and telecommunication management, distributed systems integration, application development and systems operations (Kim et al., 2003). At that stage the importance, nature and diversity of IT outsourcing was changing and companies begin to take a more strategic and proactive approach to it (Grover et al., 1996). IT outsourcing has grown rapidly since then and with the recent advent of the cloud, which refers to both the applications delivered as services over the Internet and the hardware and systems software in the data centres that provide those services (Armbrust et al., 2009) and Armbrust et al. (2009) are supported widely in their suggestion that the long-held dream of computing as a utility has the potential to transform IT outsourcing.

While business process outsourcing (BPO) is recognized as a separate domain, boundaries between BPO and IT outsourcing are difficult to define, especially when the underlying IT services are also outsourced to the same service provider. This issue is also complicated by the fact that some business processes have become IT services and certain definitions of IT outsourcing include ‘IT-enabled business processes’ (Gartner, 2013). BPO is also growing rapidly and some forecasts expect it to overshadow IT outsourcing (Oshri et al., 2009).

While Gartner (2013), an IT research and advisory consultancy, provides a simple classification of IT outsourcing functions, IT-enabled business processes, application services and infrastructure services, there are several views of what IT services and IT outsourcing functions comprise. Some suggestions for classification of IT outsourcing functional areas are simple and include project management, applications development, applications management, data centre operations, infrastructure acquisition, infrastructure maintenance, systems development and systems maintenance (Fish and Seydel, 2006). Classification is not made easier by the variance in service offerings between service providers. TCS, a large global service provider, for instance, lists over a dozen service offerings on its website (tcs.com, 2014) whereas IBM, another large global service provider, lists over two dozen service offerings on its website (ibm.com, 2014).

The same issue applies to IT outsourcing engagement options, some of which can be reconciled into two main types: total outsourcing and selective outsourcing (Willcocks and Lacity, 2009). In total outsourcing all or most (usually more than 80 per cent) of the IT budget for IT assets, leases, staff and management responsibility is transferred to an external IT provider (Dibbern et al., 2004; Willcocks and Lacity, 2009). A variation of this option is when a firm becomes more business oriented and outsources the entire business outcome, instead of focusing on the service process (Patel and Aran, 2005). In this scenario, partnerships become more relevant as sourcing options can include partnering, mergers and acquisitions (Patel and Aran, 2005). In selective outsourcing only selected IT functions are outsourced to single or multiple vendors and most IT functions are provided internally (Willcocks and Lacity, 2009).

Partnerships and collaborations are also relevant for selective outsourcing and certain models; for instance the Arana ‘Matrix of outsourcing models under different scenarios’ (cited in Patel and Aran, 2005) calls for it explicitly when there is reasonable probability of an activity becoming a competitive advantage and when a company’s internal capabilities are weaker or similar to those of its competitors (Patel and Aran, 2005). Interestingly, Patel and Aran (2005) argue that the degree of competitive advantage from the outsourcing initiative should determine the strength of the relationship needed.

Grover et al. (1996) are not alone in suggesting that the underlying motivation for IT outsourcing can be explained with two models: the resource-based view (RBV) and transaction cost economics (TCE). The RBV theory posits that a firm’s capabilities are critical for its achieving competitive advantage and that firms can fill gaps in their existing capabilities or develop them further by acquiring resources and capabilities from the market. TCE posits that firms can reduce costs by outsourcing activities to exploit market economies of scale and specialization. Research suggests that TCE is the most important motivator for IT outsourcing (Lacity et al., 2009).

TCE and RBV can be used to identify resources or services which are best suited for outsourcing due to the nature of their attributes. TCE advocates outsourcing when services are associated with low asset specificity, low uncertainty, high substitutability or low frequency of use. RBV advocates outsourcing when in-house services are not valuable, common, imitable or substitutable or when the market provides services which are valuable, rare, non-imitable or non-substitutable.

While outsourcing is well aligned with TCE, it does not necessarily help a firm achieve competitive advantage. The underlying strategic motivation for IT outsourcing can also be explained by RBV and dynamic capabilities, which are ‘the firm’s ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competences to address rapidly changing environments’ (Teece et al., 1997) in order to achieve new forms of competitive advantage. ‘Instead of capabilities, the organization has the alternative to go for the outsourcing of services or solutions’ (Patel and Aran, 2005), which ironically is the rationale for acquiring dynamic capabilities in the first place, demonstrating how well aligned RBV is with outsourcing to achieve competitive advantage.

There are also other strategic reasons in strategic partnerships, like those suggested by Ansoff (1987), and IT outsourcing can be a means to gain access to new markets and segments or to produce new or innovative products or services faster than its competitors, thereby providing a means of competitive advantage. Achieving cost leadership, a generic strategy suggested by Porter (1980), due to IT outsourcing is unlikely, given that IT outsourcing services are plentiful and easily available. Increasing IT system commoditization (Willcocks and Lacity, 2009) makes differentiation increasingly difficult; a better explanation from this school is that IT outsourcing enables a company to ‘focus on core’ competencies and that IT outsourcing’s only contribution is improving operational efficiency. Nevertheless, when TCE-based outsourcing contributes to an underlying cost-leadership business strategy, outsourcing relationships can be a means of achieving competitive advantage.

Despite its ubiquitous use in IT outsourcing ‘sourcing strategy’ rarely has anything in common with business strategy. Once a business strategy or initiative has been defined, i.e. ‘what is to be done’, sourcing strategy is the next step, i.e., ‘who will do it’ (Patel and Aran, 2005).

Willcocks and Lacity (2009) argue that IT outsourcing success should be assessed based on the extent to which organizations achieving their desired nominated outcomes during the period when those outcomes were being pursued. There are several studies on IT outsourcing outcomes and Willcocks and Lacity (2009) provide a detailed, compiled list of categorized IT outsourcing expectations. These include financial expectations (reduce costs, improve cost control and restructure IT budgets), business expectations (return to core, facilitate mergers and acquisitions and enable start-ups), technical expectations (improve technical service, access technical talent, and access to new technologies) and political expectations (prove efficiency, justify new resources, duplicate success, expose exaggerated claims and eliminate troublesome function).

Despite this framework, issues remain with assessing IT outsourcing outcomes and success: there is a lack of an accepted success construct, the definition and meaning of success differs and desired outcomes can change over time (Willcocks and Lacity, 2009). Grover et al. (1996) also provide a framework to evaluate success and introduce the notion that partnership elements are important variables for outsourcing. Their research shows that service quality and partnership elements such as trust, cooperation, and communication are important for outsourcing success.

Given the alignment of RBV with outsourcing it is not surprising that some scholars, Feeny et al. (2005), Oshri et al. (2009) and Willcocks and Lacity (2006) for instance, stress the importance of vendor capabilities. Feeny et al. (2005) identify 12 vendor capabilities (Planning & Contracting, Organisational Design, Governance, Customer Development, Leadership, Business Management, Programme Management, Process Re-engineering, Sourcing, Domain Expertise, Behaviour Management and Technology Exploitation), which they advise companies to assess. Willcocks and Lacity (2006) group these together in three key vendor competences. Interestingly, one of these is the ‘relationship competency’, which is based on a vendor’s willingness to consider a client’s values and goals while implementing their delivery model, confirming the importance and desirability of what appears to be a type of ‘partnership’ competency.

The cloud is transforming the IT sector and IT outsourcing may only become far more pervasive and extensive. By lowering transaction costs, IT allows big chunks of the economy to reshape and the IT sector looks like a pyramid where economies of scale rule the bottom and creativity and agility are desired at the top (Economist, 2014). Progress is rapid and some services that it took a company six months to get up and running in the 1990s take a few weeks today via the internet and command a lower fee (Economist, 2014).

Deloitte, a consultancy, is not alone in discussing the notion of a ‘virtual vendor’ and suggesting that the cloud may make business models such as ‘vendor as broker’ and ‘vendor as retailer’ economically feasible (Deloitte, 2013). This is very interesting from a partnership perspective as it suggests longer supplier chains and end-service providers with whom relationships may only weaken. However, nothing is certain and market dynamics will determine whether cloud sourcing will be the demise of traditional outsourcing or will result in next-generation outsourcing (Gartner, 2014).

1.2 Risks and uncertainties

There are several studies on IT outsourcing risks; Oshri et al. (2009) and Civilis (2013) provide compiled categorized lists of them. Oshri et al.’s (2009) risk list includes business risks (no overall cost savings, poor quality and late deliverables), social risks (cultural differences, holiday and religious calendar differences), logistical risks (time-zone challenges, managing remote teams and coordinating travel), workforce risks (supplier-employee turnover, supplier-employee burnout, inexperienced supplier employees, poor communication and skills of supplier employees), legal risks (inefficient or ineffective judicial system at offshore location, intellectual property rights infringement, export restrictions, inflexible labour laws, difficulty obtaining visas and changes in tax laws, inflexible contracts and breaches in security or privacy) and political risks (backlash from internal staff, perceived as unpatriotic, political instability with or within the offshore country).

Suggestions for risk lists can overlap and Civilis’s (2013) compilation of risks from outsourcing studies includes organizational risks (poor service quality, loss of knowledge, rigid collaboration, poor employee morale and loss of innovation), financial risks (hidden cost, overstated benefits, loss of revenue), contractual risks (poor contract management, wrong partner selection, power shift to supplier, lock-in with supplier) and environmental risks (legal obstacles, distance, negative press and creating a competitor).

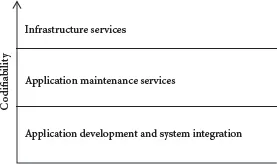

Risks can also be classified into structural and operational risks (Oshri et al., 2009). Operational risk is high when processes are opaque or when they cannot be codified and measured. Structural risk arises when the relationship between clients and suppliers may not work as expected (Oshri et al., 2009). Aron and Singh (2005, cited in Oshri et al., 2009) suggest that captive and internal functions are better suited than outsourcing when there is a high structural or operational risk. This is a common approach and explains why basic infrastructure services are so widespread in outsourcing. Refer to Figure 1.1 for examples of IT services associated with increasing levels of codifiability.

While this suggestion does mitigate risk, it has the downside that it may end up excluding outsourcing in areas which may provide the greatest benefits: innovation and competitive advantage, perhaps even at a lower cost and higher service level than being able to deliver these functions internally.

The ability for outsourcing to spur innovation is documented. Lacity and Willcocks (2014) argue that most successful companies concentrate less on cost savings and more on innovation. In a study they conducted on a successful and innovative BPO relationship, they identified gain sharing as an important element and the service provider partner is cited as saying that ‘the key message is a spirit of partnership that I don’t think exists in the other engagements that I’ve come across’ (Lacity and Willcocks, 2014).

FIGURE 1.1 Examples of common IT services with increasing levels of codifiability

Source: Authors’ own.

It is often assumed that risks and uncertainties refer to the same issue and it is necessary to make the distinction between these terms. Knight (1921) suggested that risks are situations where a particular outcome can be assigned probabilities. In other words, risk is uncertainty that can be insured against, as the quantification of risk through the assignment of probabilities to different possible outcomes lies at the heart of insurance. Uncertainty on the other hand refers to situations where it is impossible to assign any probabilities to possible outcomes: uncertainties are uninsurable and not quantifiable. There is little research on uncertainties through an IT-outsourcing lens. However, uncertainties are an important theme in this study and are examined in more detail in Chapter 2.

2

Uncertainties in Outsourcing

Datta, Surja and Neil Oschlag-Michael. Understanding and Managing IT Outsourcing: A Partnership Approach. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015. DOI: 10.1057/9781137497321.0007.

The aim of this chapter is to identify and understand the various forms of uncertainties that surround the outsourcing decision and the outsourcing process.

2.1 Introduction

Uncertainty can be generally thought of as the difficulty firms face when predicting the future. In the outsourcing context, this can thought of as the uncertainty about the outcome of the decis...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- 1 IT Outsourcing

- 2 Uncertainties in Outsourcing

- 3 Trust and Partnerships in Outsourcing

- 4 Developing Uncertainty and Trust Constructs

- 5 Findings and Discussion on Case Studies

- Conclusions

- References

- Index