eBook - ePub

Language, Development Aid and Human Rights in Education

Curriculum Policies in Africa and Asia

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Language, Development Aid and Human Rights in Education

Curriculum Policies in Africa and Asia

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The debate about languages of instruction in Africa and Asia involves an analysis of both the historical thrust of national government and also development aid policies. Using case studies from Tanzania, Nigeria, South Africa, Rwanda, India, Bangladesh and Malaysia, Zehlia Babaci-Wilhite argues that the colonial legacy is perpetuated when global languages are promoted in education. The use of local languages in instruction not only offers an effective means to contextualize the curriculum and improve student comprehension, but also to achieve quality education and rights in education.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Language, Development Aid and Human Rights in Education by Zehlia Babaci-Wilhite in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Pedagogía & Currículos educativos. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

PedagogíaSubtopic

Currículos educativos1

Introduction: The Paradigm Shift in Language Choices in Education

In this book I explore the consequences of educational choices for quality education, self-determined development and children’s rights in education for democracy in some African and Asian countries. I review theory and educational practices involving the relationship between local knowledge and language of instruction (LoI), and especially their applications to teaching and implications for rights in education. I show that current educational reforms in some African and Asian countries are failing in their efforts to improve education and suggest how educational systems and education itself in these countries could respond to children’s learning from the ground up in a more authentic and relevant way. I also reflect on education policies designed to improve literacy and numeracy in the global context and the consequences of a failure of these policies for increased socio-economic inequality. Further, the book addresses how international, Asian and African educational reformers are attempting to deliver meaningful learning to their pupils through expanding access to schooling and confronting the challenges of simultaneously improving student learning. These analyses draw on my extensive work and research experiences on educational systems and reforms in developing countries, both in Africa (the United Republic of Tanzania (URT), South Africa, Rwanda and Nigeria) and in Asia (Malaysia, India and Bangladesh).1

The analysis emphasizes that in making English the LoI and ignoring local languages in curriculum change, African and Asian policy makers have been influenced by the still-powerful notion that learning in a Western language will promote development and modernization. This is reinforced by development aid programs directed at the educational sector, many of which encourage and support the use of a non-local LoI. This book will argue that indigenous languages and indigenous knowledge need to be valued in education in order to prepare children to learn and engage in a language they understand best, and as such should be regarded as a right in education.

The book has three main goals. The first is to underline the urgency of acknowledging local knowledge for achieving quality education as a human right. There are an increasing number of books and journal articles that draw attention to the importance of rights to education. These focus on providing universal access to education, but very few have addressed rights in terms of the quality of teaching and learning. My approach is unique in providing a framework for associating human rights with educational choices, emphasizing language choices and local knowledge in educational policies.

My second goal is to flesh out a theory of language policy in education based on a review of theoretical approaches and a comparative study of selected countries (named above) in Africa and Asia. The analysis of educational policy addressed in this book builds on a solid foundation of evidence from Africa and Asia that learning in a local language is critical to quality learning. My third goal is to reflect on the challenges of achieving broader democratization through social justice in education, which involves reforming the politics of globalizing languages and supporting local curricula that emphasize equality and inclusive quality education.

Colonial languages

In the 18th and 19th centuries, colonial linguists and missionaries recorded African languages and classified them as different dialects (Makalela, 2005). In sub-Saharan Africa, African languages were either related to, or were derivatives of, Bantu. The shared communicative base was much broader than that assumed by missionaries and language scientists who have written about African languages from the 1830s to the present, for example the missionaries Isaac Hughes (1789–1870), who transcribed seTswana, and Andrew Spaarman (1747–1820), who transcribed isiXhosa in South Africa. These transcriptions led to the linguistic separation of these closely related languages. Leketi Makalela (2005, p. 151) calls this process the “de-Africanisation through displacement of African languages”. Furthermore he argues that “African languages are not so different as to impede communication, as it is canonically assumed” (2005, p. 166) and that a harmonization, rather than a segmentation, of languages ought to be made. However, he notes that:

The notion of harmonisation is often misinterpreted to mean that some African languages will be killed and that people will lose their languages and identities … But as Webb and Kembo-Sure (2000) rightly put it, this process of harmonisation does not take anything away from the speakers, but rather adds … a core written Standard for literacy, which learners from different languages acquire at school while retaining their home or spoken varieties.

(2005, p. 168)

If local languages were harmonized, it would help to protect traditions through stories, myths and songs (Babaci-Wilhite et al., 2012a). Languages with a colonial legacy, such as English, French, Portuguese and Spanish, to a smaller extent, continue to be used as official languages in many developing countries today. Africans were forced to use European languages, and this constituted a form for colonization of the mind (Ngugi wa Thiong’o, 1994). This same mental colonization took place in several Asian countries. In British Colonial India, English was made the LoI by the English Education Act of 1835, but only with the purpose of generating a cohort of clerks, peons and petty functionaries to oil the machinery of empire (Viswanathan, 1989). Thus, ironically, both English and the mother tongue (MT) can play a divisive role in gatekeeping linguistic capital (Hornberger & Vaish 2009, p. 308).

Globalizing English

English is a particularly powerful globalizing language that is influencing debates on choice of LoI in many developing countries in Africa including India, Bangladesh and Malaysia, which will be elaborated in Chapters 2 and 6. Ayo Bamgbose (2003, p. 421) notes that “language has a pecking order and English has the sharpest beak”. It carries with it a cultural context foreign to the local contexts for education (ibid.).

The embedding of English in education is a method for creating dependency, accomplished through the institution of European languages, metaphors and curricula. In recent years, the use of English as a LoI in postcolonial countries has been a subject of debate and research. Many scholars argue that English intervention in learning promotes and prolongs neocolonialism and that its expansion should be halted (Phillipson, 1992; Mazrui, 2003; Alidou & Brock-Utne, 2011; Skutnabb-Kangas & Heugh, 2012).

Today, English is used as an official or semi-official language in over 60 countries in the world and has a prominent place in a further 20 (Majhanovich, 2014). Globally, it is the main language of books, newspapers, airports and air-traffic control, international business and academic conferences, science, technology, medicine, diplomacy, sports, international competitions, pop music and advertising (Mazrui, 1997).

Braj Kachru (1990) describes the spread of English as three concentric circles to explain how the language has been acquired and how it is used. The first inner circle represents its use as an MT or/and a first language. The second circle comprises countries colonized by Britain where non-native speakers learn English as a second language in a multilingual setting, as is the case in Tanzania. The outermost circle consists of countries that dedicate several years in primary and secondary education to the teaching of English as a foreign language, such as most European countries.

Some scholars, namely Michael Kadeghe (2003), regard English as a valuable asset for global business and cross-cultural communication. Many language policy makers have adopted this view particularly in wealthy nations like the United States of America (USA) and the United Kingdom (UK), where large amounts of “foreign aid” moneys are spent on promoting English, and in sub-Saharan Africa where English is now often the sole official LoI at all levels of education (Mazrui, 2003). These perspectives ignore the issues of quality learning and cultural identity. Robert Phillipson (2000) argues that this increasing global influence of English constitutes a linguistic imperialism and counterposes the preservation of native languages in line with Tove Skutnabb-Kangas’s (2000) work on language as a human right.

Virtually all African linguists and educationalists argue for the advantages of the use of an African language as the LoI (Fafunwa, 1990; Qorro, 2003; Prah, 2009; Okonkwo, 2014). Children taught in any of the language varieties similar to their MT will have better learning comprehension than those taught in an adopted foreign language such as English, and furthermore MT education leads to more effective teaching of sciences and mathematics. An effective language policy takes care that the languages taught in education reflect everyday communication patterns.

Carol Benson and Kimmo Kosonen (2013) conclude from their research that learning in one’s MT allows for better learning of all subjects, including the learning of a second language. The language that a child masters best is the language used at home and in the local surroundings; however, the choice of language for a local school is complicated by the fact that in many African contexts there are several languages used in the community. There is not always an obvious choice of local language and this has led to many local debates on whether one of the local languages should be used or, as in the case of East Africa, whether a pan-African language such as Kiswahili should be used as a LoI (Brock-Utne, 2007; Vuzo, 2009; Babaci-Wilhite, 2013a).2

The cost of using multiple MTs in different regions is high, and there are also debates on whether this separation into regional LoI is feasible. I acknowledge the importance of this debate and the difficulties involved in the choice of a local or pan-African language, but I derive from the literature that due to the fluency of some African languages, such as Kiswahili in Zanzibar and because Kiswahili is a locally constructed language that is related to the vast majority of East African languages, that it is an obvious choice for primary schooling in Zanzibar.

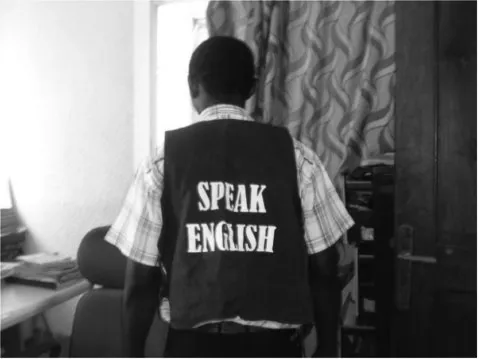

An important issue in choice of a local LoI such as Kiswahili is its reinforcement of local identity. Identity is strongly connected to parents’ beliefs, to the language spoken at home and to local culture. The overwhelming message from research in Africa is that using a language that learners use in their everyday lives will improve learning and help to maintain the connection to the local cultural context. The use of a local language in education will contribute to literacy and strengthen cultural identity. According to Moshi Kimizi (2012), the use of a local language as a teaching medium will also affect a child’s self-esteem. The learning process can be done effectively only if a child feels that her or his identity is acknowledged. The best learning environment will be created when a child feels that their language has value. Should the local language be rejected, this is equivalent to the rejection of local identity. Research shows that this sense of rejection is affecting children’s sense of identity in several African countries (Mazrui, 2003), which is a violation of human rights (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Children’s punishment when they speak their language in school3

Many schools around the world use English as the LoI in the expectation that it will bring greater academic success and mobility for their students. Several scholars in the study directed by Adama Ouane and Cristine Glanz (2006) leave no doubt that the use of MTs facilitates the learning processes in schools. Martha Qorro (2003) confirms that there is a belief in Tanzania that learning in English will improve the learning of the language; however, she points out that the LoI has another important function, in that concepts are communicated to children in the language they understand best. Bamgbose’s (1984) study in Nigeria and Grace Bunyi’s (1999) study in Kenya confirm this point, showing that when science instruction was conducted primarily in English as opposed to a native tongue, students were unable to apply concepts they had learned in class to practical situations at home. Sunil Loona (1996, p. 3) reinforces the point on the power of local language to communicate concepts when he writes, “Learning a second language does not imply the development of a totally new perspective, but rather the expansion of perspectives that children already possess.” It is important to make the points that learning in a language and learning a language have two different functions, and to combine these functions will slow and possibly stop the process of learning (Qorro, 2004). This difference has to be understood and acknowledged in the curriculum.

In Africa and several Asian countries, the policy of switching from a local language to English midway through the schooling process gives the impression that African and Asian languages are inferior to English and that the local language is somehow inadequate for engaging with complex concepts. This reinforces the sense of inferiority of local culture and at the same time is disadvantageous for those who have had little exposure to English at home. This choice in Africa and Asia has contributed to the formation of a national identity and cultural identity as exemplified in Tanzania, India and South Africa. Whichever context a child is in, s/he can hardly achieve quality learning when there are identity problems. Moreover Kosonen (2010) argues that the use of MTs produces better learning results in all school subjects and also reduces repetition and drop-out.

Local languages as cultural capital

The use of a local language in the educational system also contributes to self-respect and to pride in local culture. By reinforcing the importance of local languages, one reinforces the interest in local knowledge and culture. Ideally, one would choose a non-dominant local LoI, but in cases in which this is expensive and practically difficult to implement a local language, such as Kiswahili, that has local roots and is widely used in public spaces is a good second choice (Babaci-Wilhite, 2010).

I agree with Birgit Brock-Utne (2007) who is critical of the consequences for the development of self-respect and identity of not using the language one normally communicates in as a LoI in school. Language is part of one’s identity and part of one’s culture and a local language should be used to reinforce both through schooling. This is consistent with Rwantabagu’s (2011, p. 472) argument based on a study in Burundi where he argues that “The possession of one’s language and culture is at the same time a right and a privilege and members of the younger generation should not be denied their native rights and advantages, as provided for in article 27 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights” (UN, 1948). Furthermore, he points out that after a series of education reforms, there is still a debate in Burundi over the use of French or Kirundi as LoI. He argues for the importance of local LoI as a basis for better knowledge acquisition, and that policy makers should take evidence-based research on language and education into consideration. He also points out that African languages will enable African cultures to exist and will ensure the survival of African languages, referring to Senghor’s (1976, p. 10) point that culture evolves which entails that our school systems should aim both at cultural authenticity and openness to foreign influences, said to be “the humanism of the new millennium” (ibid.). Furthermore, he concluded that within the context of globalization, giving prominence to African languages and cultural values could be based on “interdependence and complementarity between cultures and nations”, addressing one of the most important challenges of the 21st century.

In sum, the implications of education in Africa and Asia for identity and development argue for the choice of a local LoI in education. Education must be centripetally oriented, and based on the principles of respect for human rights and cultural dignity. It must give consideration to local realities and direct its intellectual efforts and curriculum toward the achievement of freedoms that are consistent with education as a human right (Babaci-Wilhite & Geo-JaJa, 2011).

According to Skutnabb-Kangas (2000), the most important linguistic human right in education for indigenous peoples and minorities, if they want to reproduce themselves as peoples/minorities, is an unconditional right to MT-medium education in non-fee state schools, exemplified by a policy put into place by Imo State in Nigeria in 2014. Moreover, she argues that binding educational Linguistic Human Rights are more or less non-existent in African countries (ADEA, 2001) and states a pessimistic but realistic estimate that 90–95% of today’s spoken languages may be very seriously endangered or extinct by the year 2100. This means another round of colonization of the mind through cultural assimilation of non-local language and culture. Since much of the knowledge about how to maintain the world’s biodiversity is encoded in the small indigenous and local languages, with the disappearance of the languages crucial ecosystem knowledge will also disappear and be replaced with “Western” scientific knowledge if we do not acknowledge local LoI as important in education.

Local languages improve teaching and learning, as well as having significant subsidiary benefits for the society. The results from many studies around the globe demonstrate that English as a LoI hinders educational development and reinforces social inequality. A result of the transition to English LoI is a diminution of “cultural capital” in poor and socially excluded groups (Bourdieu, 1977). According to Pierre Bourdieu (ibid.), the ability to function well in school and in society will be dependent on certain surrounding factors such as parental education, the number of books in the home, the amount that a child is read to and the amount that a child is talked to. Loona (1996, p. 6) writes, “Children do not arrive at school with equal amounts of knowledge of the world … Differences in experiences in homes and in their daily lives can lead to some...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- List of Acronyms

- Maps

- 1. Introduction: The Paradigm Shift in Language Choices in Education

- 2. Educational Issues in Africa and Asia

- 3. Development Aid in Education

- 4. Educational Aid in a Human Rights Perspective

- 5. A Rights-Based Approach in North–South Academic Collaboration within the Context of Development Aid

- 6. Linguistic Rights for Appropriate Development in Education

- 7. Language-in-Education Policy

- 8. Experiences in Countries That Have Chosen English as the Language of Instruction

- 9. Science Literacy and Mathematics as a Human Right

- 10. Conclusions and Recommendations: Local Languages and Knowledge for Sustainable Development

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index