eBook - ePub

The UK Challenge to Europeanization

The Persistence of British Euroscepticism

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The UK Challenge to Europeanization

The Persistence of British Euroscepticism

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This timely contribution pulls no punches and views the UK as institutionally Eurosceptic across politics and society, from the press to defence. It represents a rich and original contribution to the emerging field of Eurosceptic studies, and a key contribution to this important issue.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The UK Challenge to Europeanization by Karine Tournier-Sol, Chris Gifford in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Nation and National Identity

1

The Essential Englishman: The Cultural Nature and Origins of British Euroscepticism

Menno Spiering

In 1989 Duncan Steen and Nicolas Soames published a book entitled The Essential Englishman. It is a coffee table book, full of anecdotes and pretty pictures of bowler-hatted, cricket-playing, beef-eating gentlemen. The title, however, is interesting. First of all it is, of course, politically incorrect. Surely women live in England, too. Secondly, the book’s title suggests that the English share a fundamental substance, an essence, of Englishness. The essential Englishman is unlike the essential Frenchman, who is unlike the essential German, and so on.

Essentialist ideas about national identity go back at least to the Classical era. Often the climate or local food is seen as the source of the different national characters that people cannot avoid acquiring. Writing in the 1st century BC, Marcus Vitruvius Pollio declared that ‘Nature herself has provided throughout the world that all nations should differ according to the variation of the climate (…). It is climate which causes the variety in different countries’ (Zacharasiewicz 1977, p. 32). In the course of the 18th century, these ideas were re-embraced with a vengeance by a host of philosophers trying to support their explanations of national differences. Oliver Goldsmith, for instance, was convinced the English were a moderate people because of the moderate English climate (Goldsmith 1760). In the 19th century, different nations were equated with distinct ‘races’, which were of unequal quality because of the differences of their ‘blood’. ‘In strength of fist’, Arthur de Gobineau stated in 1853, ‘the English are superior to all the other European races; while the French and Spanish have a greater power of resisting fatigue and privation, as well as the inclemency of extreme climates’ (Gobineau 1999, p. 152).

Today such essentialist ideas of identity are suspect, especially since the Nazi extreme of distinguishing ‘eternal Jews’ from equally ‘eternal’ Arians. If there are essential national or racial differences, these are regarded as the result of nurture rather than nature, of culture rather than climate or blood. The 1951 UNESCO Statement on the Nature of Race and Race Differences declares that ‘the normal individual, irrespective of race, is essentially educable. It follows that his intellectual and moral life is largely conditioned by his training’ (UNESCO 1951). It is by this tenet that this article seeks to investigate some of the inherent qualities of British Euroscepticism. It is argued that British Euroscepticism is of an ‘essential’ nature, in the sense that it is an enduring cultural phenomenon (‘conditioned by training’) that goes much deeper than rejection of EU rules and regulations, or the ‘dictates of Brussels’. At the root of British Euroscepticism lies a long-established tradition of contrasting the British Own with the European Other. British Euroscepticism is to a large extent defined and inspired by cultural exceptionalism.

Britain and Europe

David Cameron’s famous speech on ‘Britain and Europe’, which he delivered in London on 23 January 2013, is a good point of departure to track and trace instances of perceived divisions between the national Own and the European Other (Cameron 2013). He formulates five points, or ‘principles’, which have to be addressed in the near future: competitiveness, flexibility, the need for power to flow back to the member states, democratic accountability, and fairness. The figure of five, by the way, is remarkable. In 1966 Labour leader Hugh Gaitskell declared his party would only consent to EEC membership if five conditions were met. In 1974 Prime Minister Wilson announced he would renegotiate the Treaty of Accession on five points; in her 1988 Bruges Speech, Margaret Thatcher listed five ‘guiding principles’; and in 1997 the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Gordon Brown, formulated ‘five economic tests’ to be met before the UK could join the European Monetary Union. Apparently British politicians are hard wired to measure their relationship with the European institutions in units of five. This might be a conscious rhetorical figure (mentioning fewer than five issues lends your argument less weight, mentioning more makes you lose your audience), or this is a nice instance of intertextuality. Consciously or unconsciously, speech writer C copies speech writer B, who copies speech writer A.

Giving us his thoughts on the EU, Cameron either talks about member states (which of course include Britain), or he presents the Union as monolith, an alien body outside Britain. In this context, like many other politicians, he uses the word ‘Brussels’. For instance, Cameron objects to ‘Brussels’ setting the working hours of British hospital doctors. Frequently he uses the word ‘Europe’ as shorthand for the European Union and in these cases the same principle applies. Sometimes Britain is part of (or a member of) this ‘Europe’, and sometimes Europe is a fremdkörper, a foreign substance. Cameron states, for instance, that ‘legal judgements made in Europe’ have an ‘impact on life in Britain’ (italics added). This type of discourse on the European Union is not unique to Britain. Depending on their aims, politicians all over Europe present the Union in an inclusive or exclusive way. Your country is either a member amongst members, or it is an outsider besieged by the dictates of an entity called the European Union, Europe, or Brussels. If member states have taken an unpopular decision, it pays to present this as something inflicted by Brussels. In other cases there might be profit by claiming it was a co-decision, or even one that your country took the lead in.

It is in the preamble of his speech that Cameron reflects on the concept of Europe in wider terms, so not just the Europe of the Union. It soon becomes apparent that in this context, Cameron’s view of Europe is mainly exclusive, as an entity outside Britain. For instance, in his opening sentences the prime minister makes a distinction between, on the one hand, ‘European cities’ (as an undifferentiated collective) and English London which was badly damaged during the Second World War. He then calls the UK ‘a member of the family of European nations’, but quickly proceeds to define this member as ‘an island nation’ with a unique ‘sensibility’. ‘And because of this sensibility, we come to the European Union with a frame of mind that is more practical than emotional.’ One might ask ‘more practical’ than whom? The answer must be more than ‘the others’, on the other side of the Channel. The British are more practical minded than ‘the Europeans’.

It is not hard to find more instances of this exclusive use of the term Europe. ‘The crucial point about Britain’, the Prime Minister claims, is ‘our national character, our attitude to Europe.’ Cameron wants, on the one hand, a ‘better deal for Britain’. But then he adds he wants such a deal for ‘Europe too’. Even when he tries to be inclusive, he is in fact exclusive. ‘Ours’, Cameron says, ‘is not just an island story – it is also a continental story.’ Thus he again highlights the idea of an island nation that stands apart from an undifferentiated collection of people, over there, across the Channel, on the continent, in Europe. Finally Cameron states: ‘if we leave the EU, we cannot of course leave Europe.’ But then he follows with: ‘it will remain for many years our biggest market, and forever our geographical neighbourhood.’ The Oxford English Dictionary’s definition of ‘neighbourhood’ is ‘The people living near to a certain place; neighbours collectively.’ In other words, the Europeans are Britain’s collective neighbours. Europeans live near, but not in Britain.

By placing Britain outside Europe, Cameron is merely following a standard British practice. Europe and the Europeans can be seen as external to Britain and the British. Examples are myriad, in everyday speech (‘I like European food’, etc.), and in the media. When a majority voted that the UK should stay in the EC, the Daily Express opened with the headline EUROPEANS! (7 July 1975). Apparently the British had not been Europeans before. Another instance is the BBC show How Euro Are You? which was hosted by Andrew Marr in 2005. The aim was to measure the degree of Europeanness of the British audience by means of a quiz. People who indicated they liked wine and opera more than beer and sport were labelled European rather than British.

The connotations of ‘Europe’ as an entity outside Britain are not always negative. At the time of the UK’s first application for EEC membership the magazine Encounter asked a large number of ‘intellectuals’ what they thought of ‘Going into Europe’. The poet W. H. Auden stated:

If I shut my eyes and say the word Europe to myself, the various images it conjures up have one thing in common; they could not be conjured up by the word England. Since I am a writer the word Europe conjures up sacred names. Nietzsche, Rimbaud, Valéry, Kafka.

(Auden 1963, p. 53)

But, as is invariably the case with images of outsiders, more often than not in British discourse Europe and the Europeans stand for something negative, alien and even dangerous. Writing in Encounter, others call ‘the Europeans’ ‘undemocratic’, ‘dictatorial’ and ‘humourless’. David Marquand simply stated he disliked ‘the Europeans’ and ‘rejoices in the differentness of England.’ ‘My instinctive sympathies lie with the English who for 500 years have refused to be European’ (Marquand 1963, p. 70). It is this ‘instinctive’ conception of Europe and the Europeans which imbues British Euroscepticism with a special quality. British Euroscepticism is not just about the EU, it is about feeling un-European. A few more examples may further illustrate this point.

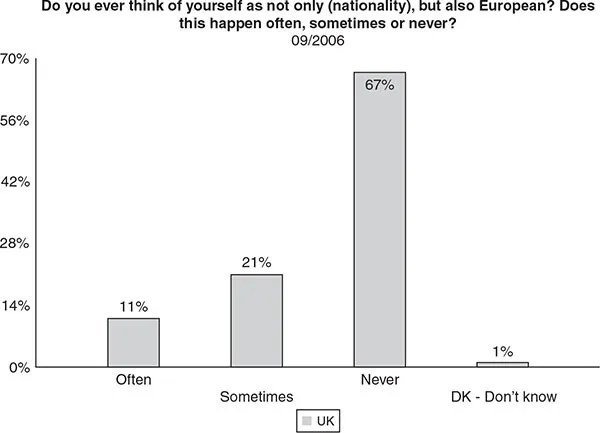

Figure 1.1 ‘Do you ever think of yourself as not only (nationality), but also as European?’

Source: Eurobarometer. © European Union, 1995–2015.

Opinion polls and surveys confirm time and again that the British public do not only have a low opinion of the European Union, they also feel ‘least European’ compared to the public in the other member states. The data supplied by Eurobarometer is quite clear in this respect. To the standard question ‘do you ever think of yourself as European?’ the UK public consistently scores the highest negative response (Figure 1.1).

It is of course well known that the vast majority of the British newspapers are Eurosceptic (Anderson 2004). In fact, they must be. Only a small percentage of British papers are sold by subscription. The majority are sold ‘on the street’, which means that they are locked in an eternal competition for public favour. It literally pays to have screaming headlines that confirm rather than challenge received public opinion. It must be for this reason that in 2010 the Daily Express started a campaign not to get Britain out of the EU, but out of Europe. GET BRITAIN OUT OF EUROPE was the enormous, page-filling headline of 25 November 2012. ‘Our political class’, the editors write, ‘bought into the European experiment after losing confidence in our nation and accepting the inevitability of decline. They viewed Europe as a life raft and clambered on board. The British people never took that view. Now it is Europe that is in decline and Britain that is being held back. It is time to break free.’

The Britain/Europe contrast is also omnipresent in political discourse. In the early 1960s, when Edward Heath reported to the nation on the Conservative government’s plans to join the EEC, he did so in pamphlets and TV broadcasts on ‘Britain and Europe’ (just as David Cameron would do 50 years later). In his famous 1962 speech, the then Labour leader, Hugh Gaitskell, reacted to the government’s plans in a way that left no doubt he regarded Europe and the Europeans as alien to Britain and the British. Britain, Gaitskell claimed, can contribute a great deal to Europe, but ‘going in’ would be a dangerous gamble. ‘So far it is hard to be convinced’, he proclaimed. ‘For although Europe has had a great and glorious civilisation, although Europe can claim Goethe and Leonardo, Voltaire and Picasso, there have been evil features in European history, too – Hitler and Mussolini’ (Gaitskell 1962, p. 36). (Note that, apparently, Europe cannot claim Shakespeare, Newton, Locke, or Oliver Cromwell.) Since the 1960s, this political discourse has hardly changed. Yes, there are plenty of references to the European institutions, but references to Europe as the great Other persist. One of the slogans of the United Kingdom Independence Party is ‘I am British, not European’ (UKIP 2014).

Culture

British European exceptionalism is so widespread because it is ingrained in British culture, low as well as high. The Internet bristles with British pamphlets and videos that are literally anti-European. A recurrent claim is that the Europeans are inherently undemocratic (remember Gaitskell’s Hitler and Mussolini), and that therefore their project – the European Union – is in fact a dictatorship alien to the British way of life. It is a plot sponsored by European big business, or even neo-Nazis. Often the Bilderberg Group is identified as the collusive lodge of businessmen and royals that is really behind the European Union (Atkinson 1996). According to the booklet Treason at Maastricht ‘the British People and Parliament have been deceived, seduced, cajoled and threatened into the European Superstate’ (Atkinson and McWhirter 1994, p. 1). In a similar vein, the magazine This England maintains that the British people are duped by traitors who need to be exposed and punished. To this end it proposed to send 30 pieces of silver to those Judas politicians who they see as having secretly sold their country to the European Union (Autumn 1996, p. 68). It is a case of Wake Up Britain, which is the title of a Eurosceptic book by the historian Paul Johnson. One day soon, he predicts, the British people will rise against Europe and the Europeans when they discover that ‘power over the minutest details of their lives is held increasingly across the Channel, deep in the recesses of continental Europe, by people who do not speak English and who have little in common with the British temperament’ (Johnson 1994, p. 59).

Similar ideas are expressed in the dozen or so Eurosceptic novels that have so far been published in the UK. In no other member state can a similar genre be found. A recent one to date is a cheap thriller called The United States of Europe (2011). The book is set in the near future and tells the story of how the UK first goes along with the total political unification of the EU member states, but then wishes to withdraw after the people of Britain have voted overwhelmingly for a patriotic independence party. The USE, however, does not want to contemplate such a secession, and eventually sends the Euro-army through the Channel Tunnel to teach the British a lesson. The islanders fight back manfully, but are seriously hampered by a second front on the English–Scottish border. Most Scots decide to help the UK in its hour of need, but a group of nationalist extre...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on Contributors

- Introduction: The Structure of British Euroscepticism

- Part I: Nation and National Identity

- Part II: Party Politics and Euroscepticism

- Part III: Eurosceptic Civil Society

- Part IV: Eurosceptic Interests?

- Index