eBook - ePub

Developmental States and Business Activism

East Asia's Trade Dispute Settlement

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Developmental States and Business Activism

East Asia's Trade Dispute Settlement

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

As firms from East Asia gain global market share they are stirring trade disputes with import-competing firms in the West. Jessica Liao analyzes the role played by government-business collaboration in determining how effective East Asian governments are in helping their exporters gain an edge over western competitors through WTO litigation.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Developmental States and Business Activism by Jessica Chia-yueh Liao in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Negocios y empresa & Negocios internacionales. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Negocios y empresaSubtopic

Negocios internacionales1

Introduction

International trade policy has been shifting from diplomacy-based initiatives to law-based initiatives, as signified by the unprecedented creation and subsequent use of the dispute settlement mechanism in the World Trade Organization (WTO). While growing scholarship offers political explanations for this recent phenomenon, few have emphasized the state factor to explain why countries choose to use the WTO dispute settlement mechanism.

This project explains why East Asian governments use the WTO dispute settlement system and how their capacity to use the system is affected by structural factors inherent in past government–business relations. East Asia offers a unique opportunity for this inquiry not only because of the strong state influence over trade policy but also because of the fact that export-led growth has been the norm and has spawned numerous export-oriented corporations in the region. This economic structure has historically made the region as a whole the most affected by export restrictions set by developed countries. This tendency has continued into the WTO era, as trade remedies, namely, antidumping, countervailing, and safeguard measures, became the most common tools for trade protectionism in both the developed and developing world. From 1995 to 2011, East Asian countries were the target of over half of the world’s total antidumping measures, while accounting for only 30 percent of world trade. It is understandable that more and more countries in the region have begun to contest export restrictions at the WTO. However, stark contrast exists among East Asian countries in terms of their WTO litigation record; some countries such as Korea, Japan, Thailand, and, recently, China, frequently contest export restrictions at the WTO, while others such as Taiwan, Singapore, and Malaysia rarely seek litigation in trade disputes. The way in which countries contest trade issues also differs; some countries contest certain issues—such as Korea, Japan, and, recently, China, on antidumping—more aggressively than others in terms of economic gain versus the diplomatic damage that the litigant government has to bear following the filing of the complaint.

In contrast with the mainstream literature on trade policy that emphasizes business pressure and the legislative branch’s power, this research focuses on government capacity to collaborate with the business sector in using the WTO dispute settlement system to solve trade disputes. Specifically, I present a thesis, which I call “the developmental state goes litigious.” My argument is that East Asian states use the WTO dispute settlement system to reduce export barriers and maintain exporters’ global competitiveness because of their enduring sense of mission directing the economy. Yet, their success in doing so is determined by the effectiveness of government–business collaboration in handling trade disputes. Government–business collaboration itself is shaped by a country’s export structure and its domestic government–business networking system. The states that successfully promote their global trade interests through the WTO dispute settlement system are the same ones that have sufficient support from and collaboration with their leading exporters. These exporters have substantial interests in, as well as capacity to, work with the authorities to solve trade disputes.

To illustrate this thesis, I select two countries that have been at opposite ends of the continuum in terms of responding to trade remedy measures—Korea and Taiwan—and examine how their governments have handled export restrictions and related trade disputes both prior to and during the WTO period. I found that while both governments have equally stressed WTO litigation as a way to protect export interests, their capacity to utilize this opportunity is shaped by the extent of their collaboration with the exporter sector. As the most aggressive East Asian state in contesting trade remedy issues, Korea has developed well-established, grassroots partnerships between the trade and economic ministries and the export sector, particularly leading exporters, in handling export restrictions and associated trade disputes. In Taiwan, among the least aggressive East Asian states in contesting trade remedy measures, partnership between economic authorities and leading exporters is not as fully developed as Korea to solve trade disputes and manage foreign trade relations. This project further finds that differing government–exporter collaboration in these two countries is rooted in their respective institutional structures, which provide different incentive schemes for the government and leading exporters to collaborate with each other. In Korea, this collaboration thrives on the top exporters’ multinational business model and their long-standing relations with the trade and economic ministries. In Taiwan, the island’s subcontracting, SME-based business model and delicate grassroots working relations between government and the majority of small and median exporters on the issue of export barriers limit government–exporter collaboration.

My research also includes a case study on China’s experience in handling foreign-imposed export restrictions. China is an important case since both its trade volume and the amount of its trade disputes are the highest in the world. The analysis takes into account the idiosyncratic nature of the export barriers China faces—its non-market economic (NME) status at the WTO—by treating it as a single case study without comparing it to Korea or Taiwan.1 Using the same analytic framework, I explain how disorganized action both within industry and with the government has not only weakened Chinese exporters’ ability to contest export barriers but made government–exporter collaboration difficult to form. I also find that while such collaboration is much needed given the increasing number of export barriers China faces in which more and more require a sophisticated cross-sector collaboration, the Chinese government has been forced to take a state-led approach to contesting those new restrictions which are less effective at remedying the affected exporters’ interests.

The rise of WTO litigation and adjudication: Current debates

Laws have become indispensable for the smooth functioning of today’s international trade relations. As trade liberalization has rapidly unfolded, instead of relying on closed-door negotiations, state governments are more willing to abide by international trade laws and to delegate their power to a third party for resolving trade disputes. This trend—also known as the trade litigation movement or trade legalization2—has accelerated since the unprecedented creation of the dispute settlement mechanism at the WTO. Under this mechanism, member states are eligible to litigate or file a complaint against another member to the WTO Dispute Settlement Body (DSB). With its adjudication power, the DSB has become a critical point of reference for the disputing parties, as well as the rest of the WTO members, to adjust their domestic legal systems and practices to be in line with WTO rules.3

The WTO dispute settlement procedure symbolizes remarkable transformation from a power-oriented to a rule-oriented international trade system. The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), the predecessor of the WTO, operates under a provisional agreement that provides informal consultations for members to resolve disputes. This agreement, as Robert Hudec describes, is merely “a nice sort of nonadversarial, nonthreatening, look-at-the-positive-side phrase for what most people would call a lawsuit.”4 The “toothlessness” of the GATT dispute settlement process is not only because of the lack of a “single, sharply defined dispute settlement procedure” but also because of the rule of “positive consensus,” under which the defendant, particularly the powerful one, could block the dispute resolution process from proceeding, making the establishment of a panel report and authorization of retaliation against the defendant impossible.5 The result of the positive consensus rule is that small countries have no alternative in a trade dispute but relying on bilateral negotiations with their great counterparts, on the one hand, and nothing prevents great countries from using punitive unilateral retaliation, such as resort to Section 301 of the US Trade Act of 1974, on the other.6

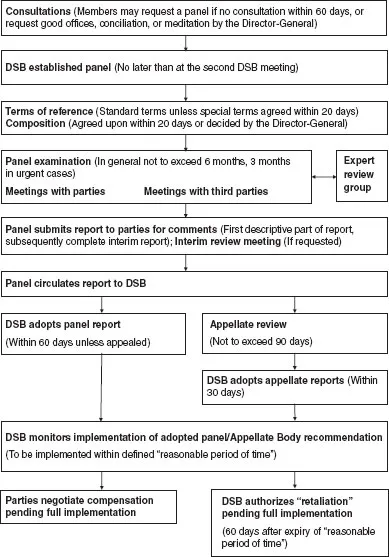

To remedy the power-oriented problem of the GATT dispute settlement process, the WTO sets out a new agreement, known as the Understanding on Rules and Procedures Governing the Settlement of Disputes (also known as DSU or Understanding), which significantly expands the procedure’s legal powers (Figure 1.1). The DSU, as Hudec describes, “gave governments an automatic right to bring their legal complaints before a dispute settlement tribunal, it made legal rulings by tribunals automatically binding upon the parties, it introduced appellate review, and it gave complaining parties an automatic right to impose retaliatory trade sanctions in cases where the defendant government failed to comply with legal rulings.”7 Many explain that the WTO as an adjudicating body is able to operate and control its member states’ behavior because of the reputation costs of non-compliance, normative pressures of rulings, and the inherent exchange of information.8 The WTO’s record in settling disputes is proven a remarkable progress in comparison with the GATT’s record. Since its inception in 1995, the DSU has received over 450 dispute notifications, within which 90 cases are settled and close to 300 cases were proceeded with panel reports.9 On the other hand, only 450 cases have been notified to the GATT for the approximately half century of its existence.

While being applauded for the DSU’s achievement, the WTO is after all not an enforcement body and the DSB rulings are implemented at the will of member states. The effectiveness of implementation is, as many observed, not perfect; countries often complain about the same trade measure of a particular country since neither the previous complaint(s) guarantee a mutually agreeable solution nor the ruling results be continually enforced.10 In addition, its long process and regular delay of implementation make it difficult to provide effective and timely solutions to disputes or to remedy the already caused business impact.11 Limits at implementing DSB rulings appall many, let alone cumbersome and highly technical legal preparation involved with the process of litigation before the DSB.12

Figure 1.1 WTO dispute settlement process

Source: Data from the World Trade Organization, “The Panel Process.”

Link: http://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/whatis_e/tif_e/disp2_e.htm. Retrieved on 11 May 2011.

Link: http://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/whatis_e/tif_e/disp2_e.htm. Retrieved on 11 May 2011.

In spite of the WTO’s mixed achievement in settling disputes, the growing use of the DSB has aroused debates among political science, economics, and legal scholars asking why state governments bring trade disputes to the WTO. Most of the current findings see economic variables as the major determinants but interpretations vary on the factors that determine a state’s litigation behavior. Those who view interests as the core of trade disputes believe that states with larger economy and trade interests litigate more since they have greater incentives to file litigation. Their studies highlight development level, trade volume, and the diversity of a state’s trade profile as the main factors affecting the likelihood that a country will file WTO litigation.13 Others use case studies of bilateral trade relations, such as US–China and India–Bangladesh trade disputes, to illustrate that trade deficit triggers the filing of WTO litigation.14

Realists, while not denying the interest factor, explain why states litigate through the lens of power distribution among states. Some realists focus on the impact of economic power on a state’s calculation as to whether to litigate and how litigation should proceed. For example, several studies found that a country’s decision in filing or handling WTO litigation is subject to the extent of trade dependence between the disputing parties because of the concern of economic impact following the litigation.15 In this sense, the decision to litigate is determined not only by the size of a country’s economy but also by its economic power to sanction or retaliate against its counterpart.16 To them, as a respondent enforces the DSB rulings at her own will, litigation is not effective if the complainant is incapable of making credible economic retaliation against the respondent through acts like economic sanctions or suspension of concessions. Thus, the power asymmetries between disputing parties may deter a country from filing a WTO complaint against its powerful trading partners.

Realists also interpret the power factor from the angle of legal capacity. Because of high transaction cost involved with WTO litigation, they explain, resources and expertise in handling this process are important factors to a government’s decision in filing a WTO complaint. They find that developed countries use the DSU much more frequently than developing country; moreover, developed countries in average receive more favorable results from DSB rulings than developing countries.17 Others also find that developing countries as a whole are constantly disadvantaged in trade disputes with developed countries due to other factors that affect their legal capacity such as language, and human and financial resources.18

Either it is trade interest or power distribution among countries that affects states’ decision in filing for WTO adjudication or to settle a trade dispute; the above analyses stress international structure and its effect on nation-states’ behavior. These studies focus on macro-level factors and assume nation-states as unitary actors in their quantitative samples. While giving a gloss explanation of WTO litigation behavior, they fall short at explaining domestic factors that affect a government’s decision to file WTO litigation and, as a result, are often ineffective to shed light on individual country’s case. For example, Christina Davis challenges the international structural perspective by pointing out that some small and developing countries, such as Thailand, are more aggressive than others, such as Botswana, which is at a similar level of development and geopolitical value.19 Essentially, macro-level studies, lumping governments and business entities as the same actor who makes decision based on the same interest concern, are limited in exploring the subnational dimension and oversimplifies the process for a commercial dispute to be escalated to a dispute at the state level.

As a result, studies on the effect of domestic politics and business actors on WTO litigation have risen to fill the gap of the previous scholarship. Among them, the most common explanation for and the most effective factor in predicting a country’s WTO litigation behavior are business pressure and contesting government–business relations under checks and balances. Focusing on relations between political parties, factions, or political leaders vis-à-vis particular firms or industry associations, they believe business demand is the underlining reason for governments to use ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Acknowledgments

- List of Acronyms

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Developmental States Contesting Export Barriers in the WTO: An Analytical Framework

- 3. The Developmental State Goes Litigious: Korea’s Pursuit of WTO Litigation

- 4. Taiwan: The Developmental State Trying to Be Litigious

- 5. The Legacy of a Developmental State: China’s Reservation in Using the WTO Dispute Settlement System

- 6. Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index