This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This provocative volume stimulates debate about lost 'heritage' by examining the history of the hundreds of great houses demolished in Britain and Ireland in the twentieth century. Seven lively essays debate our understanding of what is meant by loss and how it relates to popular conceptions of the great house.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Lost Mansions by J. Raven in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Social History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

James Raven

Abstract: The opening essay introduces the history of demolished and otherwise lost country houses in Britain and Ireland in the twentieth century, exploring controversies caused by the campaigns to save abandoned great houses. Most contemporary discussions of country house loss arise from an assumption that saving these places is an intrinsic good, but such presentations can be misleading and one-sided. Demolished houses are not neutral subjects: their decline has aroused passions for those who lament the loss of beauty (where beauty rather than incongruity has indeed been lost) and for those who mistakenly lament a halcyon lost age of social order and beneficence. This introduction suggests that we need not mourn the loss of all lost country houses. Rather, we should attempt to set the realities and representations of country house destruction within broad historical perspectives. The essays that follow encompass a range of public, cultural and political actions and attitudes that open a window upon wider debates and suppositions.

Raven, James, ed. Lost Mansions: Essays on the Destruction of the Country House. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015. DOI: 10.1057/9781137520777.0005.

At least one in six of all the great country houses existing in Britain and Ireland in 1900 had been demolished by 2000. Over 1,200 English, 400 Scottish and 300 Irish country houses have been recorded as lost during the twentieth century. This tally is certainly an underestimate and it does not include the destruction of lesser country houses and manors (nor indeed the lost great town houses of the wealthy and the aristocracy). The lost houses considered in these roll-calls were major establishments set in substantial estates. In many cases, ailing houses and estates were paralyzed less by hostility than by indifference. The destruction of great houses accelerated after the First World War, but the 1950s and 1960s were also decades of particular loss. In Scotland, 200 of the mansions destroyed in the twentieth century were demolished after 1945. Included in the destruction were works by Robert Adam, including Balbardie House and the monumental Hamilton Palace. One firm, Charles Brand of Dundee, demolished at least 56 country houses in Scotland in the 20 years between 1945 and 1965.

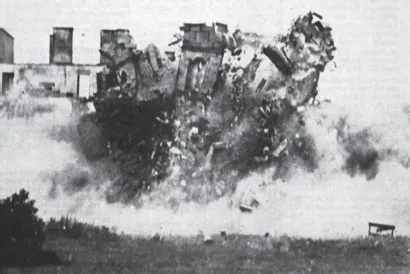

Besides physical loss are other types of loss. Where great houses still stand, survival is often partial and circumscribed. Hundreds of grand houses have been so radically reconfigured that they are no longer houses at all. Many transformed houses, performing valuable as well as incongruous roles, retain little surrounding land of their own. Such loss could be even more hidden than the ostentatious pulling down. Giving up a house was often less public and might be more subversive than blowing it up. When Rosneath Castle was blown apart in 1961, images proved sensational (Figure 1.1). Designed by the London-based architect Joseph Bonomi in 1809, this neo-classical mansion had served as a military hospital during the First World War, home to Queen Victoria’s daughter Princess Louise until her death in 1939, and as headquarters for the Rosneath Naval Base in the Second World War. By contrast, the baroque Wentworth Woodhouse near Rotherham, apparently the largest private house in Britain, remains virtually intact (unlike its surrounding estate) but became the focus of bitter and complex struggles over its use, in which failure, recrimination and private dealing were and are recurrent. A double set of death duties and the nationalization of the estate’s own coal mines reduced the wealth of its owners, the Fitzwilliam family, who sold off most of the contents of the house.

This volume debates reactions to the destruction of great houses in modern Britain and Ireland, asking questions about the causes of their loss, their representation at the time of their disappearance and the implications of current resurgent interest in great estates. What was and is the place of the great house in local society and politics, and how does this relate to popular romances that stretch from Brideshead to Downton? Ultimately, is there anything to mourn about the loss of so many of these enormous houses, when in many respects society is better off without them? At issue is the nature of ‘heritage’, the relevance of conservation, and our understanding of proprietorship and estate management in times of social, political and economic transformation.

FIGURE 1 Demolition of Rosneath Castle, Argyll and Bute, in 1961, by 220lbs of gelignite

Source: Reproduced by kind permission of the Helensburgh Heritage Trust.

Contours and causes of loss

Given that many great houses do survive, the most obvious question is what was it that doomed the rest? The question is also historic in that it is now far more difficult to destroy a great house than it was in the 1950s or even the 1970s. It was not until the Town and Country Planning Act of 1968 forced owners to seek permission to demolish listed buildings that the wave of demolitions finally came to an end.

The fount of memorialisation is Country Life which has featured an article on the history of a country house in every issue since its launch in 1897. In its first issue of 1905 Country Life lamented the loss by fire, 12 years earlier, of Uffington House, a fine Restoration house in Lincolnshire and seat of the Earl of Lindsey. Country Life commented that it seemed as if each day brought news of the loss of one of those ‘splendid houses of old England, which, though private possessions, are truly part of the national heritage’. Two years before the beginning of the First World War, in May 1912, the magazine carried a seemingly unremarkable advertisement: the roofing balustrade and urns from the roof of Trentham Hall, Staffordshire, could be purchased for £200.1 Rebuilt on a grand scale in the 1830s for the second Duke of Sutherland, Britain’s greatest landowner, Trentham Hall was abandoned by the fourth Duke in 1906. Trentham was offered to the county council, but no agreement was reached, and the mansion was demolished in 1911.

The last two unprotected and demolished houses illustrated in Country Life both went in 1972. In Yorkshire, Warter Hall (renamed Warter Priory) comprised a massive, 100-room, unappealing pile rebuilt (among others) by Charles Wilson, a Hull shipping magnate, who was created Lord Nunburnholme in 1906. Detmar Blow’s charismatic Arts and Crafts’ Little Ridge, Wiltshire, built in 1904 and incongruously extended in the 1920s, remained unlisted when it was pulled down in 1972. Many of the houses demolished in the 1960s and early 1970s had been empty and decaying for years, but as Giles Worsley noted, ‘what is surprising today is how houses in good repair of the importance of Eaton Hall [Cheshire] or Herriard Park [Hampshire] could be demolished with little concern, even from the pundits at Country Life’.2

In the Britain and Ireland of the early twenty-first century, protection and designation orders are not only in place but cannot be ignored as they once were. Buildings are listed, ancient monuments are scheduled, wrecks are protected, and battlefields, gardens and parks are registered. The enactment of these, however, has a long and convoluted history. Although the Ancient Monuments Protection Act of 1882 gave protection to a limited number of ‘ancient monuments’, property-owning MPs remained reluctant to restrict what owners of occupied (or even unoccupied) buildings might do with their property. The next Ancient Monuments Protection Act, of 1900, related only to unoccupied properties and imposed no constraints on owners’ freedom to do what they liked with their buildings. It was not until the early 1930s (as noted in Chapter 7 later) that legislation began to protect uninhabited houses. Damage to buildings by bombing during the Second World War prompted the first listing of buildings deemed to be of architectural merit and was the origin of the current Statutory List of Buildings of Special Architectural or Historic Interest. The early listings, however, often proved ineffective.

The current listing process developed from the wartime system and subsequent provisions of the two Town and Country Planning Acts of 1947, one covering England and Wales, and the other concerned with Scotland. Listing began notably later in Northern Ireland, with the first provision for listing contained in the Planning (Northern Ireland) Order of 1972, followed by the Planning (Northern Ireland) Order of 1991. In England and Wales, the current authority for listing is granted to the Secretary of State by the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act of 1990. Listed buildings in danger of decay are listed on the Heritage at Risk Register of English Heritage. The statutory bodies maintaining the lists are English Heritage, Cadw (The Historic Environment Service of the Welsh Government), Historic Scotland, and the Northern Ireland Environment Agency. In the Republic of Ireland buildings are surveyed for the National Inventory of Architectural Heritage in accordance with the country’s obligations under the Granada Convention (and where the preferred term in Ireland is ‘protected structure’).

In all parts of the British Isles and Ireland, listings do not absolutely prohibit change. Rather, listings identify buildings with exceptional architectural or historic special interest in advance of any planning stage which may decide a building’s future. All buildings built before 1700 which survive in anything like their original condition are listed, as are most of those built between 1700 and 1840. English heritage also now recognises 19,717 scheduled ancient monuments, 1,601 registered historic parks and gardens, 9,080 conservation areas, 43 registered historic battlefields, 46 designated wrecks and 17 World Heritage Sites. Some 33 Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty are also designated within England under the provisions of the 1949 National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act (and one of which features in Chapter 5 later in connection to the reclaimed Parke House in Devon). Of many examples of great houses saved by this legislation at the end of the last century is Tyntesfield, the remarkable mansion in north Somerset, rebuilt by the guano merchant William Gibbs in the 1830s. For many years, the house seemed on the brink of being broken up and its contents sold. In 2002, the National Trust bought the house with money raised from the National Heritage Memorial Fund and a popular fund-raising campaign. Even if the National Trust had not intervened, however, one thing was always certain. Tyntesfield would not have been demolished.

It is the lateness of this legislative-based listing and protection that explains much about the extent of great house destruction in the twentieth century, but it is not, of course, the originating cause. However dramatic the many demolitions of mansions and the alterations to estates in earlier centuries, the predicament for country houses in Britain and Ireland in the twentieth century was unparalleled in scale. Country houses offered visibility to the power of landownership which extended from local power and prestige to influence at Westminster. Political reform, however, ensured that county councils replaced many of the powers exercised by compliant magistrates (some themselves owners of great houses and estates) and the power of the country estates was effectively eclipsed by a more representative parliament. By the outbreak of the First World War, most landowners had accepted their reduced position and, with less immediate realisation perhaps, a radical change in the role of the country house. As Worsley puts it, ‘no longer powerhouses, these were now just family homes. Where scale and opulence had once gone hand in hand with political influence, by 1918 large houses just seemed extravagant’.

Examples of overextension followed by desperate retrenchment are legion. Typically, when fire partly destroyed the Duke of Newcastle’s Clumber Park in Nottinghamshire in 1879, it was rebuilt even more monumentally. By 1908, however, the duke had retired to live in the suburban comfort of Forest Lawn near Windsor. His heir, the Earl of Lincoln, demolished Clumber in 1938, planning to build a more convenient house on a new site, but was frustrated by the outbreak of war and eventually sold the estate. Many wealthy families owned more than one great property, encouraging the ruthless abandonment of surplus and oversized houses. The 1883 edition of Burke’s Peerage and Baronetage listed 167 peers and 99 baronets with 2 or more country houses. The Honywoods of Marks Hall in Essex, considered in the final essay in this volume, owned three massi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 Introduction

- Part I Implications of Loss

- Part II Debates and Perceptions

- Further Reading

- Index