![]()

1

Introduction: Is There a ‘Logic of Charity’?

Abstract: Despite charity being a consistent feature of life in the UK, we lack a clear understanding of what charity is, how it operates, who it benefits and what it can and cannot be expected to do. We begin by summarizing the different organizing principles found in government and charity, and note that the logic guiding charitable activity is not well understood by politicians who seek to encourage charity and harness it in support of their political programmes. The historic role and contemporary nature of charity are reviewed, then a discussion of data on public attitudes regarding the role that charity does and should play in relation to government funding highlights how those attitudes have endured and changed over the past 25 years.

Mohan, John and Beth Breeze. The Logic of Charity: Great Expectations in Hard Times. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016. DOI: 10.1057/9781137522658.0005.

The summer of 2015 brought a succession of negative media headlines and political interventions highlighting concerns about a range of charity issues, including the methods used to raise funds, the salaries of charity chief executives and the sudden closure of ‘big brand’ charities such as Kids Company. Prime Minister David Cameron spoke of ‘frankly unacceptable’ actions that damage the reputation of the sector as a whole,1 and the Chair of the Charity Commission, William Shawcross, described the situation as ‘a crisis’.2 Yet just 12 months previously, in the summer of 2014, media headlines reported on the phenomenal success of the ‘ice bucket challenge’, which raised over £60 million, largely for research into Motor Neurone disease3; the inspirational story of young charity fundraiser Stephen Sutton, who raised over £5 million for the Teenage Cancer Trust4; and widespread support for charities’ right to campaign, after being told to ‘stick to their knitting’ by the then-Charities Minister.5

Such swings in public opinion exemplify an ambivalent approach to the idea and practice of charity. Despite being a consistent, though often overlooked, feature of life in the UK for centuries, we lack a clear understanding of what charity is, how it operates, who it benefits and what it can and cannot be expected to do. This book has been written to help tackle some misunderstandings and misconceptions of charitable activity in contemporary British society, especially insofar as these affect the thinking of politicians and policymakers. Questions about what charity can or cannot do are of enduring significance, but the need to ask them is sharpened by the context of deep public spending cuts in a period of austerity. There are great expectations that voluntary efforts will arise and expand to plug gaps vacated by the state. Our evidence and analysis raise questions about whether such expectations are realistic – in particular, whether we can expect charitable initiative to respond to needs generated by rising levels of poverty, or whether charitable funds will flow to the most disadvantaged communities.

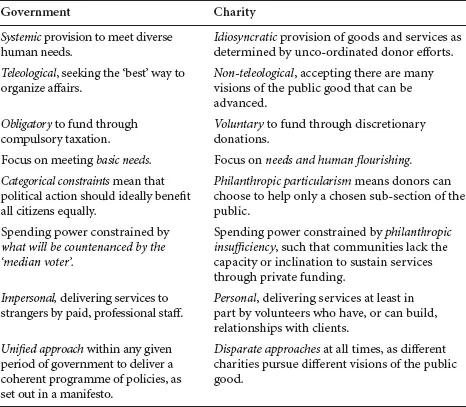

We begin by asking our central question: is there any logic to charity? Whilst the state is driven by the logic of politics and the demands of voters, and business is driven by the logic of the market and the demands of consumers, what – if anything – is the equivalent logic and driving force behind the charity sector? In Table 1.1, we offer some suggestions about fundamental differences between the dominant logic of the organizing principles and practices of the government and the charity sectors, drawing on a range of concepts from the literature that are discussed further in the chapter.

TABLE 1.1 Examples of the different organizing principles in government and charity

The existence of different institutional logics is, of course, known and acknowledged (Scott, 1995). Institutions in different parts of society – the private, state, voluntary and non-profit sectors – have distinctive intra-organizational processes and operate with different belief systems that affect all aspects of those institutions and the people who work within them, including their common practices and definitions of success. But we contend that the nature of the logic that guides charity action – especially that relating to donors’ decision-making and the consequent distribution of charitable resources – is not well understood, acknowledged or taken into account by politicians who seek to encourage charity, and to harness it in support of their political programmes.

There are some broader issues that we do not consider in this book because we have chosen to focus on the processes that underpin decisions to support charitable causes and charitable organizations, and on the distribution of those resources. Wider questions that we do not explore include: whether the power of philanthropists is justified or not, and how that relates to the source of their wealth (Sayer, 2015); the relationship between philanthropic allocation of resources (especially major donations or substantial endowed foundations) and democracy (Dobkin Hall, 2013; Eikenberry, 2009); the cost of, and justification for, charity tax reliefs (Reich, 2006); and the relationship between philanthropy and public service reform (Ball, 2008; Reich, 2005, 2006).

This chapter begins with a brief historical overview before summarizing some key features of charity in the UK in the twenty-first century, highlighting participation in giving to a variety of cause areas. We then present data on contemporary public attitudes to the role that charity does and should play, and the relationship between private and government funding for different sorts of public goods, exploring the ways in which those attitudes have endured and changed over the past 25 years. We review the main theoretical explanations of why the charity sector exists, none of which necessitates or predicts either a pro-poor bias or an equitable distribution of resources. This introductory chapter concludes by highlighting key issues relating to our current understanding of the logic of charity, which will be explored in greater detail in the body of this book.

Historical overview: charity in a welfare state

In 1948, an opinion poll found that 98 per cent of the British public felt there was no ongoing role for philanthropy because the new institutions of the welfare state had made charity superfluous.6 Yet six decades later, the ideological narrative of the ‘Big Society’, and the political reality of public spending cuts in an age of austerity, has put the focus squarely back on the charitable alternative. This shift, from being viewed as superfluous to being viewed as essential, is just one strand in our country’s ongoing difficult relationship with the idea and practice of charity.

Even our basic understanding of ‘charity’ has been – and remains – contested. In 1947 the ‘Voluntary Social Service Enquiry’, conducted by the social research organization Mass Observation, asked what meaning people attached to the term ‘charity’. Answers were characterized as ‘complex’, ‘confusing’ and dependent on the respondents’ social class and whether they identified more as a donor or as a recipient. ‘Charity’ was often defined as the transfer of money to organizations helping others, though some also talked of ‘doing someone a good turn’. The motivation for charity was widely viewed as kindness, generosity and love of fellow people, but others offered a disapproving definition: ‘Giving people something for nothing, and I don’t believe in it’ (Mass Observation, 1947). These dividing lines do not map directly onto political cleavages, despite common perceptions of a closer alignment between Conservative ideologies and voluntarism on one hand and the sometimes dismissive attitudes of Labour politicians on the other. Yet William Beveridge (1948), the architect of the Welfare State – which is often depicted as the nationalization of charity, at least in relation to health, education and basic welfare – clearly envisaged an ongoing role of private, voluntary contribution to the public good:

So at a time, in the late 1940s, when the UK was moving on from charity being the dominant provider of many key services, we find quite conflicting and ambivalent understandings of charity both in the general population and amongst the political class. Almost 60 years later, public opinion on ‘charity’ continues to lack clarity and agreement – some view it as a moral imperative and essential for maintaining solidarity in an increasingly complex and individualized society, whilst others see it as an unfortunate – and ideally unnecessary – throwback to previous centuries when people could not survive without the whimsical intervention of others. Contemporary attitudes are discussed further in this chapter.

Charity in the twenty-first century: who gives, how and to what causes

Charity is easily dismissed as anachronistic, or as something that is only needed in countries lacking a sufficiently robust welfare state. Yet charitable activity is alive and well in the present era and continues to touch the daily lives of most citizens. Despite a common perception that all public services are organized and paid for by tax-funded arms of the state, they are delivered by organizations that rely to some extent on charitable donations. For example, despite the existence of the National Health Service (NHS), charities working in the field of health (including medical research, hospitals and hospices) are the most popular cause area supported by private donors (CAF, 2015). Further examples of the presence of charitable organizations in spaces assumed to be the exclusive preserve of the public sector include charities working in child protection, mental health and education (from pre-school to higher education) as well as charities supporting people with disabilities, working with prisoners and ex-offenders and supporting ex-service men and women and their dependents. Many of the facilities that people encounter and use on a daily basis may now be in public ownership but came into being through charitable initiatives: examples include hospitals, libraries, parks, art galleries, museums, swimming pools and theatres. Contemporary donors continue to facilitate the private funding of a diverse array of activities including the arts, social welfare, medical research and educational provision. However, the embedded nature of charitable effort within the national fabric leaves many recipients unaware of the origins and ongoing income sources of the services and facilities from which they benefit.

Despite a general lack of awareness of the nature and scale of the charitable contribution to modern life, two-thirds (68 per cent) of people describe the role of charities in society as ‘highly important’ (Glennie and Whillans-Welldrake, 2014, p. 4). This finding is reflected in data published in the most recent edition of the UK Giving survey (CAF, 2015): 70 per cent of British adults report donating money to charity at some point during 2014, with 44 per cent doing so in a typical month. Women were more likely to donate (43 per cent in a typical month, versus 38 per cent of men), though the average monthly donations of men were slightly larger, at £41 versus £36. Cash is the most common form of giving, with over half (55 per cent) of donors making cash donations in 2014, compared to giving by direct debit (30 per cent), playing charitable raffles and lotteries (27 per cent), participating in fundraising events (19 per cent) and writing cheques (9 per cent). While online and text giving are growing in popularity, they remain for now relatively minor in terms of the volume of funding (CAF, 2015). Tax reliefs to individual donors – principally Gift Aid, which is available on all donations made by income taxpayers – have grown substantially, both in terms of the numbers of donors claiming the relief and the total value: from a total cost to the Exchequer of £110 million in 1994–95, to almost £1.2 billion in 2014–157 (HM Revenue and Customs, 2015).

There are over 160,000 registered charities in England and Wales, almost 24,000 in Scotland, and an uncertain number, estimated at between 7,000 and 12,000, in Northern Ireland, where a Charity Commission (separate from the one for England and Wales) has only recently begun to compile a register.8 Our statistics refer to England and Wales, but we note that a somewhat more inclusive set of eligibility criteria in Scotland mean that the numbers of registered charities are larger relative to population. Most charities are small and run entirely by volunteers. However, one in twenty (6 per cent) have an annual income over £500,000, and this small fraction accounts for the vast majority (89 per cent) of total voluntary sector income (NCVO, 2015).

If we measure the volume of charitable activity in terms of the numbers of registered charities, there is long-term stability and some signs of recent increases. Over the period since the Register of Charities was established in its modern form (1961) there has been steady expansion but much of this reflects administrative processes, as more organizations have been deem...