![]()

PART I

Understanding and Developing Shared Entrepreneurship

This section focuses first on understanding what shared entrepreneurship (SE) is, its success in organizations, and why other organizations may need to adopt it. Second, it focuses on what are the common elements in SE enterprises relative to leadership, governance, innovative processes, and culture. The culture chapter also covers the progressive human resource management processes found in SE enterprises. What becomes clear in this section is that SE represents a paradigm shift in how firms are led and operated, and that firms that are to survive and thrive in the twenty-first century cannot operate as traditional command and control firms.

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Shared Entrepreneurship: Toward an Ethical, Dynamic, Empowering, Freedom-Based Process of Collaborative Innovation*

Frank Shipper, Charles C. Manz, Karen P. Manz, and Bill Nobles

Shared entrepreneurship (SE) is becoming recognized as an organizational model that can succeed in a rapidly changing global marketplace where the hierarchical command and control model cannot.1 Hierarchical command and control stifles innovation and often fails to reward those who are responsible for an innovation.2 Innovation, whether product, process, or organizational, is the driver of success. This has always been true, but it is more critical today than ever before because of rapidly changing technological advances and consumer preferences. The academic evidence is sketchy because shared entrepreneurship is an emerging and growing practice although a limited number of organizations have been using it for 50 or more years. Those that do practice shared entrepreneurship appear to have a better chance of survival than those that don’t.3

Shared entrepreneurship organizations do not give up control, they just do it differently. As will become evident in this book, shared entrepreneurship is a fundamental paradigm shift from the traditional command and control organization. Peter Drucker in his classic 1954 book, The Practice of Management, wrote about self-control and responsibility when hierarchical control was the preeminent model of management.4 Herzberg identified responsibility as a key motivator.5 Studies of shared entrepreneurship organizations, including ours, found frequent use of peer control via peer monitoring and social reinforcement.6 Sometimes this is done through formal peer-to-peer mentorship programs, other times informally. In addition, vision-led freedom, a shared compelling vision of success, inspires people to achieve their potential and clarifies when self and peer control should be exercised. Control in shared entrepreneurship organizations substitutes the use of self, peer, and shared vision for mechanistic and hierarchical forms of control.

Organizations that practice shared entrepreneurship such as Southwest Airlines, the fourth largest airline in the United States, and NUCOR, the largest steel producer in the United States, are forcing some of their competitors into bankruptcy in their respective industries. Others are developing new product lines, such as W. L. Gore & Associates or are reviving failing plants as SRC Holdings has done. All of these companies practice shared entrepreneurship (SE), but none of them do it the same way. SE is simply a term that captures the key operating components of these firms and other companies featured in this book that has allowed them to survive and thrive in the rapidly changing global marketplace. Shared entrepreneurship is an ethical, dynamic, empowering, freedom-based process where all are encouraged to share innovative ideas and then are supported with appropriate resources to develop these ideas and enabled to share in the rewards of success. The key operating components will be defined later in this chapter and illustrated throughout the book.

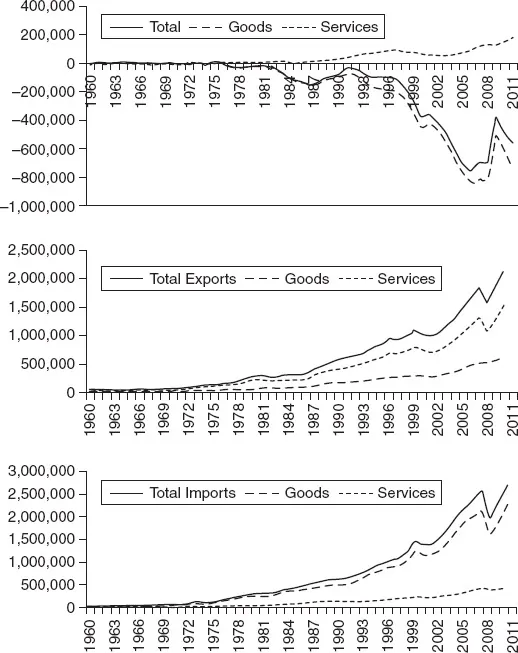

As Thomas Friedman observed in his book The World Is Flat, global competition is forcing companies to do things cheaper, quicker, and/or better worldwide.7 Price competition is moving jobs that make low value-added products from high-wage to low-wage countries. Low value-added products are those where the operating profits margin is low such as in the manufacturing of apparel sold at low-end department stores and discounters. The movement of such jobs to low-wage countries is evident when you look at figure 1.1, which reports the United States Balance of Payments from 1960 to 2011. The imbalance has grown since the early 1970s, but a breakdown between goods and services shows that the imbalance has been driven by goods such as raw materials (e.g., oil) and consumer goods (e.g., clothing and consumer electronics), products typically with low embedded value-added. In contrast, for services, the United States had a positive balance of payments during the same time period. Services by their very nature have a higher value-added. There are products such as the latest microprocessors that have high value-added. Organizations that practice SE are better prepared to participate in the global economy because they tend to be more innovative than hierarchical command and control organizations.8 Thus, the former offer higher value-added products or services more than the latter.

The converse has also become apparent in that high-wage countries cannot compete well based on incremental productivity changes against low-wage countries. For example, the labor costs in manufacturing for the Philippines, Mexico, Poland, and Taiwan are 5 percent, 18 percent, 23 percent, and 24 percent, respectively, of the United States’ according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics in 2010.9 China’s and India’s are probably equal to or less than those of the Philippines. Thus, it is hard to conceive how companies in high-wage countries that focus on incremental productivity improvements can compete against those in low-wage countries. Incremental productivity changes should not be ignored; they just should not be the focus of global competitors based in high-wage countries. They cannot compete on how much they produce; they must compete on the added value embedded in their products, processes, or services. Germany is a high-wage country that has done this and become the financial savior of the European Union.

Figure 1.1 US balance of payments in millions, 1960–2011.

Source: US Census Bureau, Foreign Trade Division.

Companies in high-wage countries must compete on brains, not brawn. To do this they must innovate; they must compete on disruptive process, product, or service innovations. For example, NUCOR has developed numerous process breakthroughs including “Castrip” technology that produces solid sheets of steel while consuming 84 percent less energy than the traditional steelmaking facility.10 Through its development of innovative processes both in production and in human resource management, NUCOR has grown in the US market and expanded overseas. It is an example of how a company that practices SE can compete in the global market place while producing a commodity priced product.

Silicon Valley was built and continues to grow based on disruptive product innovations. SE is widely practiced there (e.g., Google). Continuous improvement has been displaced by continuous innovation as the key to surviving and thriving. For example, distributive computing displaced mainframes, iPods displaced Walkman, and smart phones have displaced personal digital assistants (e.g., PalmPilots) and are displacing iPods plus both still and video digital cameras. In this competitive environment, mistakes are tolerable, such as Intel’s Pentium 5 floating point decimal errors, as long as they are corrected; stagnation is not. Every innovation that yields a competitive advantage has a life cycle of introduction, growth, maturity, and decline just as markets have a parallel life cycle. For organizations to grow or even maintain market share they must continuously innovate or they will experience decline.

Some may argue that the preceding are isolated examples of companies that practice SE and have success. To the contrary, a three-year study of 780 mostly large companies found that those that practiced SE had lower voluntary turnover, increased intent to stay among employees, and higher return on equity than other companies.11 Another study of 41,206 employees in 14 companies at 323 work sites found that SE improved firm performance.12 In addition, there are studies of multiple companies that suggest that those that practice SE can weather economic recessions better than those that do not.13 Thus, there are a number of studies of firms that suggest that those that do practice SE are more successful than those that don’t.

Technology and the global market are evolving and co-evolving, but many organizations are not.14 Technology as it has evolved allows outsourcing without any time lag. In some cases, such as with medical transcriptions, on-time performance is improved because the transcriptions are frequently done in India while the West sleeps.15 As the standard of living improves for people in India, the companies and employees buy more equipment and services from the West. Macro input/output can track the gross economic changes, but what will coevolve at the micro level is unpredictable. For example, who knew that the overabundance of bandwidth created by the bursting of the technology bubble would lead to phone centers abroad or that phone centers abroad would lead to unprecedented demand for consumer products and electricity within a country such as India? The failure of organizations in India to respond to increased electrical consumption due to greater use of consumer products has resulted in unprecedented power outages. Some will say that this is an unfair example because power is a regulated industry. The failure of Kodak, Sears, IBM, AT&T, Xerox, US Steel, General Motors, United Airlines, and others to evolve is just as apparent. Some of them are mere shadows of their former selves, others taken over, and still others bailed out by the government. Companies that practice SE, contrary to the view of some of their critics, do respond faster than hierarchical command and control organizations.16 Thus, they are more likely to evolve and coevolve in step with technological and marketplace changes.

Shared Entrepreneurship

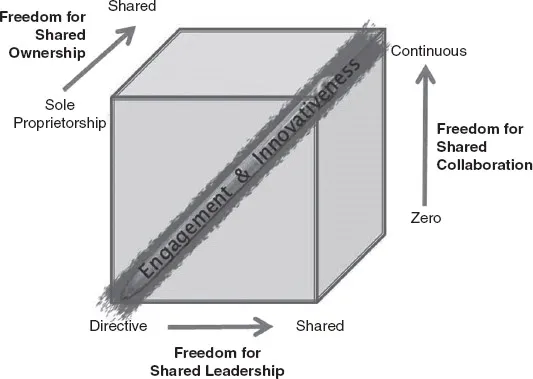

The four components of SE are illustrated in figure 1.2: shared leadership (SL), shared ownership (SO), shared collaboration (SC), and freedom. The first three components are more complex entities and can be viewed as processes or loose structures. The fourth component, freedom, is a principal core value that is expressed through the first three components. The next five chapters will expand on how these principles operate in greater detail. In addition, they will illustrate the role freedom, the fourth component, plays in creating and sustaining SE throughout the organization.

Shared Leadership

SL can be described as an ongoing mutual influence process where both designated and emergent leaders participate in the influence process.17 That means everyone is potentially a leader, at least some of the time. Who leads at any given moment depends on the capacities and experiences of the people involved and the immediate requirements of the situation. SL is related to many other concepts, including distributive leadership, freedom-based management, shared governance, industrial democracy, employee involvement, employee engagement, and employee participation. SL is the term we choose because it denotes clearly the opportunity for all employees to engage actively in a full range of responsibilities, including leadership, innovation, and ownership, throughout the organization. W. L. Gore & Associates has anchored the manner in which employees are encouraged to engage though its four guiding principles, which will be addressed later. Other SE organizations encourage SL through values statements. For example, at one minority employee stock ownership plan (ESOP) company any proposed action can be questioned by anyone based on the corporate values. In an organization practicing SL, everyone has the freedom and the responsibility to emerge as a leader.

Figure 1.2 The four components of shared entrepreneurship.

Leadership can be viewed as a performance art. As Douglas McGregor pointed out, individual leaders take their cues from their underlying assumptions about the nature of people. ...