This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Volatility in Korean Capital Markets summarizes the Korean experience of volatile capital flows, analyzes the economic consequences, evaluates the policy measures adopted, and suggests new measures for the future.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Volatile Capital Flows in Korea by K. Chung, S. Kim, H. Park, C. Choi, H. Shin, K. Chung,S. Kim,H. Park,C. Choi,H. Shin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Macroeconomics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

Overview

1

Overview of International Capital Flows*

Kyuil Chung, Hail Park, and Changho Choi

Introduction

The purpose of this book is to explore how Korea has managed international capital flows over the last two decades. Unfortunately, less than ten years after Korea had barely recovered from the aftermath of the 1997 Asian financial crisis, the country was hit by yet another crisis, the global financial crisis. There were many causes for these two crises, but international capital flows were prime among them. Therefore, a good understanding of capital flows in and out of Korea during the last two decades is essential to derive some useful lessons from Korea’s experiences. However, before exploring capital flows in Korea, we first provide an overview of international capital flows in general in order to place the Korean case in a broader context.

International capital flows occur primarily either between advanced economies (AEs), or between AEs and emerging market economies (EMEs). Capital flows between AEs have significant implications for understanding the global financial crisis, as is clearly documented in the “global banking glut” hypothesis,1 which argues that European banks’ reallocations of capital into the US mortgage market, mostly funded by their US subsidiaries in the US financial markets, were the direct cause for the US subprime mortgage crisis. Nonetheless, it has long also been contended that global imbalances were the remote cause for the global financial crisis, a view famously dubbed the global saving glut hypothesis.2 Global imbalances literally refer to current account imbalances between AEs and EMEs. In hindsight, however, underlying these current account imbalances were also capital flows, which mirrored current account conditions.

Reflecting this observation, the G20 has set a policy dialogue agenda for dealing with global imbalances, involving for example the Framework and the Reform of the International Monetary System. The former discusses ways of coordinating individual countries’ macropolicies to keep their current account imbalances within appropriate levels. The latter concerns the management of global liquidity, strengthening the role of Special Drawing Rights (SDRs), and improving the governance structure of international decision-making bodies such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Against this backdrop, we focus here on the general features of capital flows involving AEs and EMEs, which provides a more plausible lens with which to assess capital flows in Korea. Despite the importance of capital flows between AEs, they are beyond the scope of this book.

International capital flows have a wide range of aspects that deserve in-depth scrutiny, but this chapter will present only a select review, thereby setting the stage for discussions in subsequent chapters. Specifically, we focus on three key aspects of international capital flows that are most relevant to understanding capital flows in Korea. First, we consider theoretical explanations of why capital flows occur, and examine how they hold up with real world data. Second, we document some stylized facts about international capital flows to EMEs, and look at how they have evolved over time. Last, but not least, we investigate the key driving forces behind international capital flows to EMEs, and draw some policy implications.

Theory and Reality

Our focus in this section is to introduce a general theory explaining why international capital flows arise, and to then compare the theory with the reality to derive a useful workhorse for subsequent discussions. According to the balance of payments identity, the current account mirrors the capital plus the financial accounts; the current account is conceptually net savings (savings – investment). Thus, an exploration of savings and investment behaviors renders theoretical clues for the understanding of capital flows.

Though theoretical models provide predictions concerning the behaviors of capital flows and their consequences, they may not be consistent with the facts observed in the real world. We will therefore compare the theoretical predictions with the empirical findings. Finally, we will examine the world balance of payments data broken down into that for two groups, AEs and EMEs, which will give us a summary picture of capital flows between these two groups. This brief sketch will provide a useful guideline for analyzing the issues discussed in this section.

Theory

Conventional theory concerning international capital flows draws heavily on the maximizing models that became common in the field of international economics in the early 1980s. These views, which follow the neoclassical model tradition, include the intertemporal approach to the current account and the open-economy version of the Real Business Cycle model.

For our discussion we adopt the intertemporal approach. The intertemporal approach to the current account tells us that economic agents make decisions on adjusting their savings and investments in order to maximize their life-time utility. In this approach, capital flows are a reflection of economic agents’ decision-making as to consumption and investment over long-term horizons (Obstfeld and Rogoff, 1996). This theory of course assumes that market distortions to the economy do not exist, and that economic agents have full access to information on market conditions, which might be untrue in the short-term but will eventually be realized in the long-term.

This approach suggests three implications with respect to international capital flows. The first relates to consumption smoothing. Economic agents make adjustments to their current and future consumption (savings) in order to maintain a certain level of consumption over both periods. The same could be the case with countries: individual countries can smooth out their consumption by utilizing international capital flows. Countries faced with temporary slumps are able to do so through overseas borrowing, and countries facing temporary booms through overseas lending. The second implication concerns growth enhancement through allocative efficiency. Free capital movement across borders facilitates a more efficient allocation of resources and thereby stimulates economic growth and the development of financial systems (Mishkin, 2009). These direct benefits are accompanied by several other collateral benefits, such as stronger discipline in macroeconomic policies, improved governance structures, and greater competition. The third implication relates to the direction of resource flows. Given EMEs’ strong investment demand and high productivity of capital, we can easily predict capital flows from capital-abundant AEs, where the returns to capital are low, to capital-scarce EMEs where these returns are high.

These theoretical foundations have provided powerful motivations for EMEs to implement capital account liberalization over the last three decades.

Reality

These traditional views cannot, however, explain certain phenomena in reality. Although consumption smoothing is the first benefit expected from international capital flows, the former has in fact turned out to become more volatile, especially in EMEs. Specifically, if risk can be shared through international capital flows, the ratio of volatility of a particular country’s consumption to the volatility of its GDP growth should fall, or the correlation between a country’s growth in consumption and the growth of world output (or world consumption) should be larger than the correlation between the country’s consumption growth and its own output growth after capital liberalization. While some of the literature presents empirical evidence of improved risk-sharing in industrialized countries since the opening of their capital markets, such cases are rarely found in EMEs or developing countries.3 Second, even though international capital flows may facilitate economic growth, it appears that they also cause higher instability in the financial markets of many EMEs, increasing the likelihood of crisis. This was clearly evident in the Asian financial crisis and the recent global financial crisis. Third, unlike the prediction of theory, it has been observed that capital has moved not only from AEs to EMEs (downhill flows) but also from EMEs to AEs (uphill flows) since the 2000s. Various studies4 have emerged to explain the reasons for these uphill flows. Some of the reasons cited are institutional deficiencies in EMEs, higher true returns of capital in AEs, and EMEs’ desire to hold safe assets in AEs.

This inconsistency between the conventional view and reality has led to the emergence of alternative views, which have gained traction over time. According to these new views, the allocative efficiency of the neoclassical tradition holds only where market distortions do not exist. Since there are many distortions in EMEs, however, critics argue that the predictions of conventional theory have little to do with the real world. They even assert an absence of uniform evidence for the hypothesis that financial globalization delivers a higher rate of economic growth.5 The disparities between theory and reality and the existence of contrasting views indicate that we need a comprehensive and balanced view of international capital flows in order to understand the full picture.

World Balance of Payments

The foregoing observations motivate us to look at the balance of payments data of world economies divided into AEs and EMEs, which is crucial for grasping the overall features of international capital flows. Under the principle of double-entry bookkeeping for the balance of payments, the sum of the current account and the aggregate capital account (capital and financial accounts + changes in reserves) should equal zero. This concept is useful for identifying the characteristics of capital flows between AEs and EMEs that are the primary causes for global imbalances.

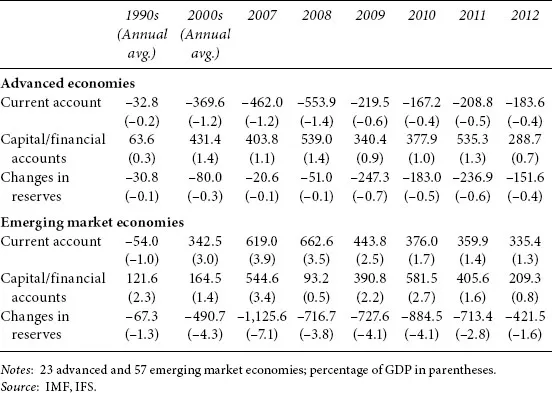

Table 1.1 presents the evolution of balance of payments from 1990 to 2012. Countries surveyed for this purpose are divided into two groups: 23 AEs and 57 EMEs. Detailed examination of the balances of payments of these countries reveals substantial differences in capital flow patterns between the 1990s and the 2000s. During the 1990s, AEs and EMEs registered slight current account deficits, indicating that global imbalances were not pronounced back then. During this period, current account balances were determined mainly by the characteristics of individual countries, for example, whether they were manufacturing powerhouses or resource-exporting countries. The current account deficits in both groups were compensated for with capital and financial accounts surpluses. One notable feature is that EMEs’ reserve holdings, represented by negative numbers in their changes in reserves, were small during this period. This indicates that the so-called global saving glut phenomenon was not apparent during the 1990s.

Table 1.1 Trends of international capital flows (billion US$)

The 2000s in contrast has seen serious global imbalances, as AEs have recorded large deficits in their current accounts while EMEs have posted significant current account surpluses. AEs’ current account deficits have been offset by surpluses in their capital and financial accounts because EMEs have sent their funds to purchase safe assets in AEs. AEs have also usually held small amounts of foreign reserves, with their flexible exchange rate systems functioning as shock absorbers. As a result, the changes in their reserve assets have shown small negative numbers. In the case of EMEs, the twin surpluses in their current accounts and their capital and financial ac...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Part I Overview

- Part II Capital Account Liberalization and Its Consequences

- Part III Policy Responses before and during the Crisis

- Part IV Macroprudential Policy after the Crisis and Suggestion for Institutional Reform

- Part V Epilogue

- Index