This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Hazlitt the Dissenter is unique in providing the first book-length account of Hazlitt's early life as a dissenter. As the first multi-disciplinary account of Hazlitt's early literary career, it provides a new insight into the literary, intellectual, political and religious culture of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Hazlitt the Dissenter by Stephen Burley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Social History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

William Hazlitt (1737–1820) and the Unitarian Controversy

‘One of the fathers of the modern Unitarian church’

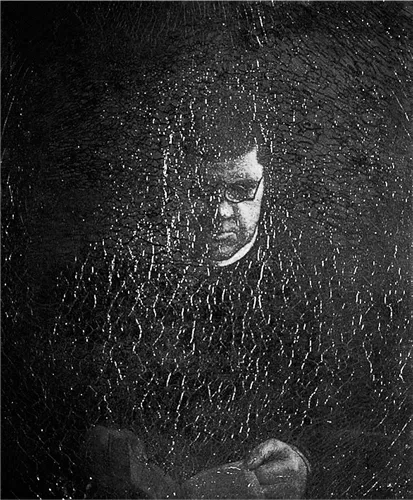

One of my first attempts was a picture of my father, who was then in a green old age, with strong marked features, and scarred with the small-pox. I drew it with a broad light crossing the face, looking down, with spectacles on, reading. The book was Shaftesbury’s Characteristics, in a fine old binding, with Gribelin’s etchings […] Those winter days, with the gleams of sunshine coming through the chapel-windows, and cheered by the notes of the robin-redbreast in our garden (that ‘ever in the haunch of winter sings’) […] were among the happiest of my life […] The picture is left: the table, the chair, the window where I learned to construe Livy, the chapel where my father preached, remain where they were; but he himself is gone to rest, full of years, of faith, of hope, and charity!1

When invited to write an obituary of his father, Hazlitt instead composed ‘On the Pleasure of Painting’, the essay which opened his 1821 volume Table-Talk. It concludes with a poignant elegy that evokes a scene from the winter of 1801 in the old school room in the Presbyterian Chapel in Wem, a small market town in rural Shropshire. Hazlitt stood before his father – brush in hand, easel at his side – to paint his father’s portrait. The picture, which is now held at Maidstone Museum, was a success for the aspiring artist: it formed part of the Royal Academy exhibition at Somerset House in 1802 where the image of the 68-year-old Dissenting minister hung rather oddly alongside that of the playwright and baronet, Sir Lumley St George Skeffington (1771–1850).

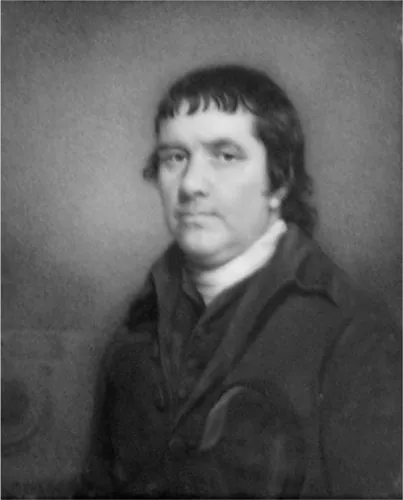

The portrait, and the account of its composition in the subsequent essay, offer an important insight into Hazlitt’s reverence for his father and the depth of his admiration for what he had achieved. Yet the popularity of Hazlitt’s essay, and the resonant image of the ageing, bespectacled, benevolent minister, has had the effect of eliding the more combative, aggressive, and polemical nature of Hazlitt Sr’s personality. George Thatcher (1754–1824), an American congressman who had befriended the Hazlitts in the 1780s, remarked that Hazlitt Sr was ‘a plain-spoken, unreserved man, who does not possess much of the sneaking virtue, commonly called discretion’.2 In 1782 Richard Price, the Dissenting minister at Newington Green in London, warned that he was ‘too open in his declarations and too imprudent in his conduct’;3 and in 1787 Theophilus Lindsey, the founder of the first Unitarian chapel in England, observed that he was ‘not one that has sacrificed much to the graces’.4 Such evidence finds support in another, earlier portrait painted by Hazlitt’s brother, John. Here there is none of the mild benevolence of William’s picture: instead we are confronted by a stern, resolute, and somewhat forbidding glare. With the eyes fixed directly at the onlooker, Hazlitt Sr is presented as a strong, determined figure, at once accustomed to and prepared for confrontation.

Figure 1 William Hazlitt’s portrait of his father reading from Shaftesbury’s Characteristicks of Men, Manners, Opinions, Times (2nd edn, 1714), c.1801. Reproduced by permission of Maidstone Museum & Bentlif Art Gallery

Figure 2 John Hazlitt’s miniature of his father. Reproduced by permission of Maidstone Museum & Bentlif Art Gallery

Born and raised in Shronell, County Tipperary, Hazlitt Sr was the eldest of five children. His father was a Presbyterian Calvinist who worked as a flax factor and sent his son to a local grammar school, and then on to Glasgow University. At Glasgow Hazlitt Sr attended Adam Smith’s lectures on Moral Philosophy which formed the basis of A Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759). As with many young men, his university days shaped his subsequent life and career. Mid-eighteenth-century Glasgow had become a focal point for anti-Trinitarian controversy and the university was in the throes of the ancient theological struggle between Calvinism and Arminianism.5 In 1729 John Simson (1667–1740), Professor of Divinity, had been tried and found guilty of heresy,6 and in 1743 William Leechman (whose lectures Hazlitt Sr attended) had also been accused of anti-Trinitarian heresy in the debates surrounding his appointment.7 Hazlitt Sr’s exposure to the liberal theology of the university prompted a significant decision: he renounced the Calvinist theology of his upbringing and embraced Unitarianism.

His first ministerial appointment was as Sir Jocelyn Conyers’s private chaplain at Sawbridgeworth in Hertfordshire, and from there he went on to minister to Presbyterian congregations in Wisbech, Marshfield, Maidstone, and then Bandon in Cork. It was during his time at Bandon (1780–83) that his vocal sympathy for the cause of American independence ‘brought upon him the reproaches of his fellow-townsmen’.8 George Bennett’s History of Bandon records that whenever the locals saw him in the streets ‘they used to cry out to beware of the black rebel’.9 Such was his enthusiasm for the new republic that he and his family soon left Ireland. In the spring of 1783 they were on the first boat to dock in New York harbour with news of the peace negotiations between Britain and the United Stated which would bring an end to the Wars of Independence.10 The Hazlitts spent more than three years in the new republic, leading a largely itinerant life in New England and Maine: here Hazlitt Sr achieved some of his most notable successes, promoting anti-Trinitarian theology and playing an active role in the conversion of the King’s Chapel, Boston to Unitarian forms of worship. On his return to England in 1787 he applied for a vacancy at the Presbyterian chapel in Shrewsbury, but was overlooked in favour of John Rowe (1764–1832), a 23-year-old Unitarian who had recently graduated from New College, Hackney. In need of a salary, he had to accept the post of minister to the small, rural congregation in Wem. In ‘My First Acquaintance with Poets’ his son bitterly lamented this humiliation. His father, he writes, ‘had been relegated to an obscure village, where he had to spend the last thirty years of his life, far from the only converse that he loved, the talk about disputed texts of Scripture and the cause of civil and religious liberty’.11 The sense of disappointment is also confirmed by his sister, Margaret. She writes that in November 1787 ‘it was my father’s ill-fate to settle [in Wem] and bury his talents until old age prevented his further usefulness’.12 He finally retired from the ministry in 1813, moving to Addlestone and then Bath, before spending his last two years in Devon.

Hazlitt Sr had worked for over fifty years in the Presbyterian ministry. He was an important member of Joseph Priestley’s circle and was instrumental in the development and dissemination of Unitarian theology on both sides of the Atlantic at the end of the eighteenth century. Furthermore, he was a talented and prolific religious writer who was the author of 11 separate publications and a regular contributor to some of the leading newspapers and religious publications in England, Ireland, and America. After his death in 1820, he was described in the Monthly Repository as ‘one of the fathers of the modern Unitarian church’.13 In many respects, however, he remains a neglected figure. Although his son has long been recognised as one of the great English essayists, Hazlitt Sr’s achievement has yet to be fully appreciated. Writing in the 1830s, his daughter Margaret complained that her father’s work in the United States, ‘preach[ing] the doctrine of the divine Unity from Maryland to Kennebeck’, had been ‘entirely overlooked and the whole worked ascribed to Dr. Priestley, who went there so many years after him’.14 In fact, more recent accounts of the origins of English and American Unitarianism continue to dismiss Hazlitt Sr’s role: J. Rixey-Ruffin has described him as ‘only a marginal member’ of Joseph Priestley’s circle, adding that he was ‘their least liked and most peripheral figure’.15 Although J.D. Bowers’s study acknowledges that he ‘was one of the first to bring English Unitarianism to the United States’, he writes that ‘an inability to clearly articulate the broad expanse and depth of the English Unitarian tenets, led to failure when it came to his ultimate goal’.16 Similarly, Andrea Greenwood and Mark Harris note that Hazlitt Sr was responsible for ‘the first attempts at evangelizing America’, before concluding that ‘his mission was a failure’.17 This chapter draws on a range of new evidence and previously unattributed writings to challenge these assessments and to remap the parameters of Hazlitt Sr’s achievement as a minister, writer, and theologian. By taking John Hazlitt’s lesser-known portrait of a fiery and indomitable Irishman as its starting point, it presents the first synoptic account of his life and career since Margaret Hazlitt’s diary of the 1830s. In doing so it builds a portrait of a man who was at the very centre of the Priestley circle, a pioneer of late eighteenth-century Unitarianism in England and America who was also one of the most significant influences on his son’s mind and work. As his great-grandson noted, Hazlitt Sr ‘was not merely the father of his son William, but the parent of his son’s genius’.18 This chapter, then, works to unearth the roots of Hazlitt’s Unitarian inheritance through a detailed study of his father’s life and work.

‘A mark of separation’

On Monday 19 May 1662 Sir Robert Turner, the Speaker of the House of Commons, introduced a Bill ‘for the reformation of all abuses in the public worship of God’: ‘We cannot forget’, he lamented, ‘the late disputing Age, wherein most Persons took a Liberty, and some Men made it their Delight, to trample upon the Discipline and Government of the Church’.19 Later that day the royal assent was pronounced: the Bill of Uniformity of Public Prayers and Administration of Sacraments became law, standardising religious services by imposing the Book of Common Prayer on clergymen throughout the country. By the end of the year around 2000 clergymen who resisted the new religious settlement of the Restoration resigned or were expelled from their congregations. The Great Ejection, as it became known, was the genesis of Protestant nonconformity and the ejected clergymen and their families were the first nonconformists. Four additional acts of anti-nonconformist legislation were passed in the early 1660s, ahead of the Test Act of 1672, which required anyone who held civil or military office to take the Sacrament within three months of their appointment.20 Until the accession of William III in 1688, nonconformists were persecuted and proscribed: denied the rights and liberties of the rest of society, they were, as Hazlitt noted in one of his essays, subjected to the ‘instinctive hatred’ of their countrymen.21 After the Toleration Act of 1689 the legal disabilities for nonconformists were eased. Nonetheless, throughout the eighteenth century they continued to be excluded from the church, army, navy, magistracy, and parliament, and prohibited from taking degrees at the two English universities.22 As David Wykes has noted, nonconformists who sought to be teachers or ministers did so only at the risk of prosecution.23 Despite the alignment of eighteenth-century Protestant Dissent with the Hanoverian regime, by the end of the century the oppositionist identity of nonconformity was as sharply defined as it had ever been. In 1790, as Dissenters lobbied for the repeal of the Test and Corporation Acts, Anna Letitia Barbauld addressed the opponents of reform: ‘You have refused us’, she argued, ‘and by so doing, you keep us under the eye of the public, in the interesting point of view of men who suffer under a deprivation of rights. You have set a mark of separation upon us, and it is not in our power to take it off’.24 Throughout the 1790s the oratory and writings of Edmund Burke had worked to forge a close association between British Dissenters and the rebellious, regicidal activities of their ancestors, the seventeenth-century Puritans. Burke invoked an array of historical precursors from Wat Tyler to Hugh Peters, the Independent minister rumoured to have been Charles I’s executioner, in order to undermine the pacific pretensions of the Dissenters.25 To be a Dissenter in the late eighteenth century was, then, to ‘suffer under a deprivation of rights’, to be marked by the stigma of the regicide of Charles I, and consequently to be ostracised from the centres of civic, political, and religious power in England.

Although Dissenters were united by a shared cultural history of suffering and persecution, by a libertarian ideology that reached back to the seventeenth century, and by a sharply oppositionist identity, they were divided by the particularities of their faith, doctrine, and practice. Eighteenth-century religious Dissent was, if nothing else, characterised by its pluralistic and fissiparous tendencies. In the broadest sense, Dissenters shared an ideological commitment to the foundational belief that Scripture was the only rule of faith, and that individuals had an inviolable right to private judgment in interpreting scriptural evidence: as the General Baptist minister John Evans stated, ‘The principles of which the Dissenters separate from the church of England […] may be summarily comprehended in these three; 1. The right of private judgment. 2. Liberty of Conscience, and 3. The perfection of scripture as a Christian’s only rule of faith and practice.’26 Beyond that, however, a bewildering array of constantly changing denominations, sects, and groups, each, as John Seed writes, ‘with histories as diverse as their theological tenets’,27 competed against one another in a religious environment that encouraged and embraced pluralism. At the most heterodox extreme of the Dissenting community were those, like the Hazlitts, who denied the Holy Trinity. Unitarianism was a Christian heresy prohibited by law until 1813 (the year that Hazlitt Sr retired from the Presbyterian ministry) and Unitarians, alongside Roman Catholics, were excluded from the provisions of the Toleration Act. Whereas Trinitarian theology stipulated that Christ was ‘coeternal’ and ‘consubstantial’ with the Father, the Unitarians believed that the early Christian Church was, for the first three centuries after Christ’s death, monotheistic in worshipping the Father alone: the worship of the Son and Holy Ghost were therefore idolatrous corruptions introduced as a consequence of the efforts of the early ecumenical councils to establish a unified Christendom.28 Yet, even within Unitarianism there were, as in Dissent more generally, significant divisions when it came to christological matters. Although the Arians and the Socinians both adopted the term Unitarian, their theological and philosophical differences were a persistent source of tension and disharmony.

Arianism took its name from the early Christian Presbyter, Arius (c.250–336), who, in a dispute with Athanasius following the Council of Nicea in 325 AD, argued that Christ, although a divine being, did not exist eternally, but was created by, and was therefore inferior to, God. Denounced as heretical by the earl...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1. William Hazlitt (1737–1820) and the Unitarian Controversy

- 2. ‘A slaughter-house of Christianity’: New College, Hackney (1786–96)

- 3. A ‘new system of metaphysics’

- 4. Retrospective Radicalism: Pitt, Patriotism, and Population

- Conclusion: ‘A sublime humanity’

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index