eBook - ePub

Blind Workers against Charity

The National League of the Blind of Great Britain and Ireland, 1893-1970

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

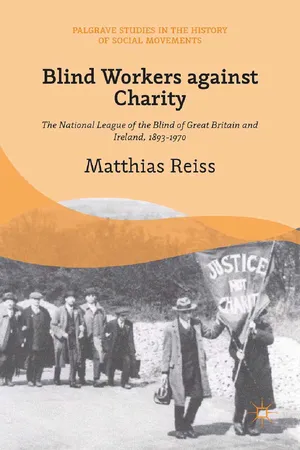

Blind Workers against Charity

The National League of the Blind of Great Britain and Ireland, 1893-1970

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Founded in 1893, the National League of the Blind was the first nationwide self-represented group of visually impaired people in Britain. This book explores its campaign to make the state solely responsible for providing training, employment and assistance for the visually impaired as a right, and its fight to abolish all charitable aid for them.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Blind Workers against Charity by M. Reiss in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Geschichte & Sozialgeschichte. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

GeschichteSubtopic

Sozialgeschichte1

New Union or Poor People’s Movement? Building the National League of the Blind

One of the most striking features of the League is its longevity. As a radical poor people’s movement founded in the last decade of the nineteenth century, the League’s odds of surviving as an independent organisation for more than a hundred years had been slim. By their very definition poor people’s movements are unstable and the League was no exception. Yet the organisation was able to overcome sectional differences, internal power struggles and programmatic disputes as well as an almost constant scarcity of resources to emerge with a stable, sustainable and effective structure in the mid-1930s. By that time the League had managed to see off all its major rivals and could legitimately claim to be the most representative voice of sightless workers in Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Members of the League were given seats on committees dealing with the welfare of blind people, employers accepted the organisation as a collective bargaining partner, and the TUC as well as the Labour Party had made the League’s key political demands their own.

The price of these impressive achievements was centralisation and a complete dependence on the trade union movement. During the first four decades of its existence the League changed from a lively and relatively loose federation of branches into a centralised organisation dominated by the Executive Council and the Central Office in London. This process was not achieved without resistance from the grassroots, but mirrored the development of the wider trade union movement in Great Britain. While the League was able to significantly amplify its influence through its affiliation with the TUC, its trade union status also created problems and confusion. This chapter will analyse why the League decided to become and remain a registered trade union and how this status contributed to its longevity.

Creating a history

Foundation narratives can contribute to an organisation’s survival by providing cohesion and meaning. Pinpointing the start of a movement is essential for creating a narrative of steady progress which promises to eventually culminate in the fulfilment of the movement’s demands or goals. Commemorating those who created the movement and highlighting their vision and sacrifices offers an opportunity to emphasise the values on which it is founded and can encourage as well as inspire members. The Labour Movement systematically began to use the so-called Tolpuddle Martyrs for these purposes in the early 1930s. The six men from Dorset were arrested and sentenced in 1834 to transportation for seven years for administering an illegal oath when forming their Friendly Society of Agricultural Labourers in Tolpuddle. Following a wave of criticism and protest the six individuals were pardoned two years later, but the memory of the injustice they had suffered remained alive within the Labour Movement. In 1932, however, the TUC lifted the commemoration onto a whole new level when it began to develop plans for marking the upcoming centenary of their convictions. Among other things a play was produced, a book published and a memorial created in Tolpuddle in the form of six cottages for retired agricultural workers, each named after one of the martyrs. The TUC also unveiled a plaque, held a demonstration, created a museum in the central hall in Tolpuddle and started an annual festival. All this served to inspire a movement in crisis and provide it with a new focus and sense of purpose. The example of the six men and the trade union values they supposedly stood for were celebrated along with the progress made by the Labour Movement since 1834.1 To this day the Tolpuddle Martyrs are portrayed as ‘key to the formation of modern trades’ unionism’ and they have become ‘some of the most celebrated names in the trade union martyrology’.2

At the same time the TUC elevated the six men from Dorset ‘to a representative standing in the movement’s history’, the National League of the Blind developed its own foundation myth which likewise centred on martyrs, pioneers, collective struggle and sacrifice.3 The League’s founders became ‘old warriors who, mostly sightless but farsighted, pointed and led the way in showing how organisation could benefit those whom they sought to serve’.4 Members of the League were warned to never ‘ever underestimate the trials and tribulations of the pioneers, who were often victimised’, and their sacrifices were presented as both the foundation upon which subsequent generations were able to build as well as a debt which needed to be repaid through the continuation of their work.5

It took a while before the League felt the need to write its own history. The first suggestion to write and print a history of the organisation was made by the Edinburgh branch in 1927 but unanimously rejected by the Executive Council who found that ‘owing to the cost and labour entailed [ … ] no useful purpose would be served by launching on such a scheme’.6 Only a few years later, however, the Executive Council changed its mind and decided to produce a handbook ‘to present in a convenient and concise form the progress in Blind Welfare Services during the last fifty years in Great Britain, with particular reference to the influence exercised by the Nation League of the Blind’.7 An appeal to all members to provide ‘reliable information regarding the activities of the League since its inception’ was issued in June 1931 and the handbook was finished in the following year.8 The League’s efforts to construct a celebratory narrative of its history therefore only slightly preceded the TUC’s decision in 1932 to commemorate the centenary the Tolpuddle Martyrs’ convictions. Both efforts were inspired by a sense of crisis, although the League’s problems were more of an internal nature, as will be shown later on.

It would take another seventeen years after the Handbook before the League published a new account of its history and mission.9 By convention the League had started to celebrate its moment of birth from when it first registered as a trade union and a Golden Jubilee Brochure was published in 1949 to mark the fiftieth anniversary of this event.10 Edited by the League’s General Secretary T. H. Smith and with a foreword from the TUC’s General Secretary Vincent Tewson, the brochure offered an official and concise treatment of the League’s history.11 Although the Golden Jubilee celebrations focused on the year 1899, Smith decided to start the League’s foundation narrative with a meeting of a small group of blind workers in South London in 1891.12 Their attempt to organise was described as ‘a weak and ill-conceived effort which speedily collapsed’, but it allowed him to link the League’s inception to the ‘new trade unionism’ of that period and the iconic London Dock Strike of August 1889 which came to symbolise it.13 Stressing that ‘blind people were not immune’ to the forces which fuelled the growth of non-craft trade unions from the 1880s onwards, Smith suggested that it was not a coincidence that ‘the first attempt at organisation among blind workers occurred in South London, the centre of the dockers’ historic struggle, and just two years after its victorious conclusion’.14 Writing in 1949, Smith conveniently ignored the fact that the dockers’ success was short-lived. In London their union was practically defeated by the end of 1890 and the Dock, Wharf, Riverside and General Labourers’ Union only survived in strength around the Bristol Channel. Concessions gained by other trade unions of non-skilled workers during that period were likewise quickly lost again as employers started to fight back immediately after the strike of the dockers.15 Nevertheless, Smith claimed that the workers in the London docks had ‘demonstrated that unskilled labour could be organised and held together by militant leadership; that it could be marshalled to fight its own battles and fight them successfully’.16 The support that Ben Tillett, the leader of the dockers, gave to the League from 1920 onwards probably helped to maintain the myth that the London Dock Strike of 1889 provided the spark for the League’s creation. Given the legendary status this conflict had within the Labour movement by 1949, the League was eager to embrace this invented tradition.17

According to the Golden Jubilee Brochure, the other major factor contributing to the creation of the League was the report of the Royal Commission on the Blind, the Deaf and Dumb in 1889, the same year that the London Dock Strike took place.18 In contrast to the somewhat questionable impact of the latter, the influence the Royal Commission had on mobilising the blind community is obvious. Established in 1885 the Royal Commission revealed the poor conditions in which many blind people lived and suggested steps to address this problem. Its recommendations regarding the education of blind people were implemented with the passing of the Elementary Education (Blind and Deaf Children) Act of 1893, but its proposals to provide industrial training and workshops for blind people in every major city were not carried out.

The Act of 1893 set a precedent for state action on behalf of the visually impaired and thereby provided an incentive for future agitation. In the same year a small conference of blind people, mostly from Manchester and London, met and issued a manifesto entitled ‘A Blind Person’s Charter’, thereby linking their nascent movement to the agitation of the Chartists half a century earlier. The document criticised the existing charitable organisations as inefficient and corrupt, denounced the workshops for the blind as ‘sweating dens’ and demanded that the state should take direct responsibility for both the employment and the adequate remuneration of blind workers.19 Branches in London, Manchester, Oldham, Cardiff and other cities were formed and loosely united in the following year under the title National League of the Blind of Great Britain and Ireland in order to promote the aims listed in the Blind Person’s Charter.20

The branches corresponded with each other but were not integrated into an organisational structure and many of them quickly ran into problems. In an effort to avoid the collapse of the League in their region the Northern England branches united under the authority of an Executive Committee at a conference in Manchester in November 1897 and elected Ben Purse as their General Secretary.21 A Dublin branch was founded in 1898 which also affiliated with the Northern Section.22 The London branch had apparently collapsed by that time. In September 1898 Purse announced in the League’s organ, the Blind Advocate, that he had received ‘definite information’ about ‘strenuous efforts’ being undertaken to reorganise the ‘late London branch’ of the League.23 These efforts apparently took place in the Limehouse and Poplar area in East London and the first activities of the Limehouse branch under the leadership of W. H. Rooke were reported in the Blind Advocate in December 1898. Among other things Rooke organised a public meeting at Limehouse Town Hall which was presided over by the trade unionist William Charles Steadman, who was also a member of the London County Council and the newly elected Liberal MP for Stepney. Ben Purse also gave a speech at that meeting but was only referred to as ‘a blind man’ from Manchester.24

Nevertheless, the contact between the Northern and the London section was already closer by that time than the League’s Golden Jubilee Brochure suggests, and Rooke was elected to the new Administrative Council of the Northern section in January 1899.25 Although the London section appointed William Banham as its own secretary in 1899, the signs were set for a merger of the two sections.26 A national Code of Rules was drafted and the League registered as a trade union in December 1899. The foundations for the subsequent election of a representative Executive Council were laid at a conference at Derby on Easter Monday 1900. Banham was appointed as the League’s General Secretary while Purse was elected National Organiser in 1901. By the time of the 1902 Trades Union Congress in London the League had also affiliated to the TUC and successfully moved its first resolution in favour of state aid during that Congress.27

The League’s foundation narrative presents the creation of the organisation as a new beginning and hails it as ‘a trade union of a new kind’.28 This was a misrep...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- List of Acronyms and Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1. New Union or Poor People’s Movement? Building the National League of the Blind

- 2. ‘Justice not Charity’: Framing the Message

- 3. Mutually Exclusive Principles? Trade Unionism and Charity

- 4. The Limits of Radicalism: Politics and Protest in the 1920s and 1930s

- 5. Success at Last? The League and the Consolidation of the Welfare State

- 6. A Changing Relationship: The League and Charity in the Post-War Era

- Appendix A: Past Officers of the National League

- Appendix B: Songs

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index