This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The first ethnographic study of the trend toward religious, parochial schooling in urban Pakistan, this book provides data from over fifty-Karachi area schools to establish the complex reasons middle- and upper-class families enroll in religious Islamic schools.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access New Islamic Schools by S. Riaz in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Comparative Education. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Comparative EducationChapter 1

Introduction: Understanding Tradition, Modernity, and Class in Islamic Education

The expertise involved in making chat, a South Asian snack mix of dumplings, sauce, and crackers, lies in how perfectly one blends all the ingredients. In the summer of 2005, I visited a madrasa (religious seminary) to collect information for a pilot study on different school systems in Karachi. The school’s administrator, Qari Mohammed Asghar, informed me that, in addition to working in the madrasa, he owned and ran a private school in another area. I asked him what courses were offered at that school. He said that his school offered a blend of all the government-approved secular subjects in a prestigious, private school environment, alongside Quranic memorization (hifz) and Quranic exegesis (tafsir) courses offered at the low-prestige madrasas. I asked him why he didn’t open a madrasa instead of blending different curricula in a new type of private school. He replied, “Because people want chat!”1

The private schools Qari Mohammed Asghar referred to are what I term Islamic schools, an emergent, alternative form of religious schooling in Pakistan. In Urdu, people usually term these schools as Islami (Islamic) schools to distinguish them from madrasas. Though some Islamic schools existed in the 1990s, they have proliferated as an alternative educational regime since President Musharraf’s crackdown on the madrasas in 2002. Post–9/11, Pakistani madrasas came under state scrutiny and were investigated by local and international media for promoting religious extremism. I went to Karachi in the summers of 2004 and 2005 to conduct pilot surveys on the madrasas and their clientele and to compare them to private secular schools and their clientele. I met parents who told me that they were choosing the private Islamic form of schooling because it provides traditional Islamic education as well as modern, secular education through the British O-level system. The O-level system, a colonial legacy, is more prestigious than the national system, known as the matriculation system. Curious about this unique religious educational phenomenon, I returned to Karachi in the summer of 2007 and lived there for a year exploring these chat-like schools that Qari Mohammad referred to and discovering why they are attractive for middle- and upper-class Karachi parents.

So far, no systematic study has been conducted on this education system in Pakistan. My aim here is to examine the emergence and continuous demand for this unique form of schooling among middle- and upper-class Karachiites from, first, a politico-historical perspective, and second, a socioeconomic perspective. For the first, I provide a background of the types of schools in the country to understand the gaps that these parochial schools are filling for urbanites. Next, I examine how state policies regarding the country’s Islamic ideology and its role in education and lifestyle have influenced middle- and upper-class citizens’ choice of Islamic schools. To this end, I trace the political story back to Zia-ul-Haq’s martial law (1977–1988), which marked Cold War politics and the Afghan jihad against the Soviet Union in the 1970s. This era is important in understanding the politico-ideological environment in which many Pakistani parents choosing Islamic schools for their children today grew up. The era marked the first strong mullah-military alliance that weak democratic governments afterwards were not able to revert and that culminated in the proliferation of these schools under another martial law, that of Pervez Musharraf, from 1998 to 2008.

For the socioeconomic perspective, I examine private schools in relation to their facilities and English as the medium of instruction. Why are some parents no longer choosing private secular schools for their children? Why are they no longer creating Islamic subjectivities through madrasa education? Until a decade ago, Islamic education in the country was not associated with prestigious Western (O-level), secular education. How then are Islamic schools transforming the concept of Islamic education? These questions guide my narrative in the chapters that follow. In examining how private Islamic schooling caters to the religious, sectarian, class, ethnic, and political aspirations of Karachi parents, I attempt to widen the theoretical understanding of religion in the context of education and to add complexity to the analysis of Islamic education. I argue that different types of religious education create a variety of religious subjectivities. In addition, as the private Islamic schooling phenomenon highlights, religious education may create not only religious subjectivities but also subjectivities that are simultaneously class, ethnic, sectarian, gender, and political.

Spread over 2,193 square miles, Karachi’s population is more than 18 million. As the largest city, seaport, and financial center of Pakistan, Karachi is home to diverse religions, Islamic sectarian traditions, ethnicities, and linguistic and communal groups. The diversity becomes increasingly complex with constant interprovincial migration for employment, refugee flows from Afghanistan, and the presence of international workers. I collected surveys and conducted formal and informal interviews with students, parents, teachers, and administrators in 15 Islamic schools. Out of these, two were run by the Ismaili Shiite community and three by the Twelver Shiite community. One was a non-Muslim Zoroastrian private religious school that I examined for comparison with Islamic schools. I discuss this school in chapter 4. The other nine Islamic schools that I visited belonged to Sunnis, who form the majority sect in Pakistan. Two were run by the Sunni linguistic business community, the Memons, and one by the followers of the Sunni subsect Ahl al-Hadith. Three belonged to the network of schools in Karachi established by the Sunni religious political party, Jamaat-e-Islami, whereas the rest were “commercial,” meaning the administrations did not follow any sectarian or political ideology and operated more like private secular schools.

For comparative purposes, I collected data from five private secular schools and four male and female Sunni and Shiite madrasa branches. Because my aim was to examine the educational choices of middle- and upper-class urbanites and because madrasas are usually associated with the lower class, I concentrated on the Guidance Network of madrasas (pseudonym) in particular, for comparison with private Islamic and secular schools because it attracts educated middle- and upper-class children, housewives, and working women. By and large, I focused on female madrasas because, as a woman, male madrasas were not accessible, other than through the formal, supervised visits in which administrators met me indirectly through my male escort, my father.

The lower-middle-, upper-middle-, and upper-class families I spoke to, who can afford private school tuition, were largely salaried classes and small and big businesspersons. Similar to the private secular schooling system, private Islamic schooling also has its own hierarchy. Accordingly, some Islamic schools have been opened by entrepreneurs in upper-class areas and have better facilities. Others have been opened by entrepreneurs in middle- and lower-middle-class residential areas inside rented apartments. The ways in which class and religious subjectivities are negotiated in Islamic schools varies with the income group to which the schools cater.

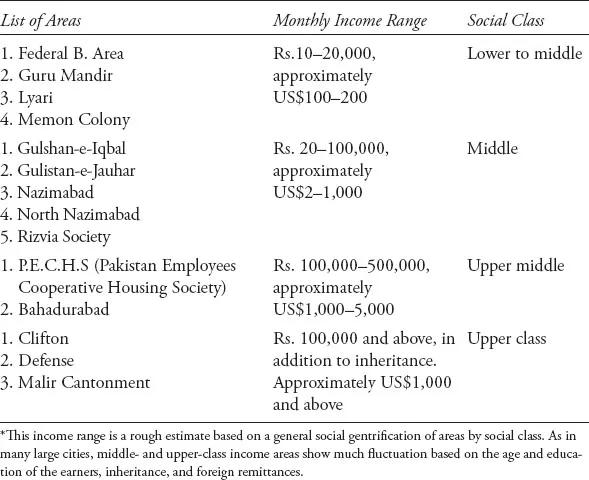

To represent the various social backgrounds and class aspirations of the people who support Islamic schools and to understand how urban parents evaluate tuition costs and school facilities and how they associate prestige with Islamic schools in high-income areas, I visited schools in diverse income areas of Karachi—four low- to middle-income areas, five middle-income areas, three upper-middle income areas, and three high-income areas. My assessment of income areas in Karachi was solely based on housing and estate prices. Table 1.1 below lists the Islamic school with the corresponding income class of people who either lived in those areas or who were choosing an Islamic school there for social mobility, a topic that I discuss in more detail in chapter 5.

Table 1.1 Economic and Social Standing of Islamic Schools and Their Patrons Based on Income-Level Areas*

Besides diversity across income levels, Islamic schools are also diversified along political, ethnic, and sectarian lines. To obtain a nuanced picture of these schools, I collected data around three aspects of the schooling process. First, I examined the schools’ daily routine, the basic pedagogical structure at the preprimary, primary (grades 1–5), and secondary (grades 6–10) levels. Second, my interest was to understand how aspirations and experiences of school administrators, staff, parents, and students define the actual pedagogical process to create various religious, sectarian, secular, gender, class, ethnic, and political subjectivities in the students. Third, I examined the school curricula to understand how it contributes to the creation of religious, modern, and gender subjectivities in the students. My interviews with administrators and teachers helped me understand their perceptions as conveyors of knowledge. With permission from the administrators, I talked with students during break times to understand how they perceive the school environment and missions—especially in comparison with private secular schools and madrasas—and how these perceptions align with the expectations of their families.

At all three kinds of schools, most of my conversations with the informants were in Urdu, Pakistan’s national language. However, English, Pakistan’s official language, has a higher prestige value than Urdu, so, on several occasions, I used English to interview my informants at the English-medium Islamic schools and private secular schools and outside the school setting.

When I was not visiting schools, I spent time with families in which children went to Islamic schools. Through formal and informal interviews, I came to understand the aspirations, socioeconomic and educational backgrounds, and ideological and professional concerns of these families. In addition, I collected various textbooks, as well as pamphlets, advertisements, and brochures that could help me understand this schooling phenomenon.

Throughout the book, the schools’ names have been replaced by categorical abbreviations to protect identities. For example, I use JIMA for Islamic schools established by alumni of madrasas operated by the Deobandi Sunni sect, which follows the religious political party of Pakistan, the Jamaat-e-Islami.

Anthropologists born in the East and trained in the West who have observed their native societies have shared the experience of how “being home” played out during fieldwork. Srinivas states that mere nativeness does not provide the anthropologist immunity to the complexities of his or her own culture.2 Describing his experience of researching in Mysore as a native Brahmin Hindu, the author reveals how some Brahmins objected that he was not following rituals particular to his caste in the conventional ways and was socializing with the lower castes. In my case, being raised in Karachi as a product of one of its private secular schools, the social and educational atmospheres of my field site were familiar to me. Yet the minute I told interviewees that I was examining schools as part of a doctoral research project in the United States, they would ask, “So are you with the FBI or the CIA?” It was hard to convince people that the United States had not sent me back to obtain inside information on the activities of religious schools in Pakistan. It was only when I began to highlight details about the middle-class neighborhood in which I was living with my parents that middle-class families began trusting me with information. Once, I was taking speedy notes about nazira (Quranic recitation) at an Islamic school when the proprietor, who was highly suspicious of my motives for coming back from the United States, sent his wife over to me. She sat next to me and read my notes out of the corner of her eye. I asked her whether she would like to give me her opinion and asked her name. She said it was Nadra, which means priceless. I wrote nazira. She corrected me, and I apologized, explaining that it had only been two weeks since I had returned and that I could really use her help in coming back to my language and culture. “Yes, you must have lost plenty of it. Come to our school often and you’ll relearn it.”3 Such moments came as a relief to me, because in those moments my informants were able to see me as someone whom they could save from Western culture and re-enculturate in Pakistani culture, rather than someone who was there to find out their secrets and relate them to the American government.

My morality in the United States was checked with questions such as, “There are Muslim students’ associations there. Are you a member or not?” “Did you live in the dorm there?” When I would satisfy my interviewees that I lived far away from the dorm culture that many Pakistani families with relatives studying in the United States conceive as the epitome of demoralization in the West, I would next be asked if my roommates were Muslim. These were some of the ways in which people regularly ascertained my religiosity and my closeness to Pakistan’s cultural values before trusting me with any information.

Similar to what Arab women anthropologists have noted about their fieldwork experiences at home, in Pakistan, I became much more aware of my femininity.4 The expectations of informants, neighbors, family, and friends to behave like a proper Pakistani woman were stifling at first. As a young, single woman out asking questions, I was under constant pressure to represent the moral upbringing of my family, in particular, my father. Very often I would ask about the school and instead hear, “And your father lets you do this?” I transformed my gestures, postures, and style of walking to suit the tastes of what men and women wanted to see: sometimes a daughter; sometimes a young woman who is not only less knowledgeable than the men, but also the least knowledgeable among women because she is still single; and sometimes a woman who desired to study Islamic education to become more pious, like the women she sought to interview. I learned that my informants felt more prepared to meet someone with my background than I felt in meeting them. Sometimes, it was hard to convince people that I was collecting information only for my studies and not for intelligence services. At other times, it was hard to convince people that I was a serious fieldworker, not some native girl who was fooling people by asking them personal, financial, and professional questions. I learned to cover my head all the time and, for one year, bought and wore only the clothes that were full-sleeved, not bright in color, and did not follow the latest fashion. In sum, a native anthropologist often has greater disadvantage because he or she has stayed far away from the parts of culture to which he or she does not relate. Having to immerse in these areas of culture as an observer then becomes a struggle to unlearn one’s cultural ways in order to relearn them from the point of view of the culture objectified.

Without a husband or a child, my only way of gaining status, prestige, respect, and legitimacy was by relying on my education. Very often it ushered an insistence on the part of the informants to answer my questions in English, using a Pakistani prestige criterion to impress me. It would take some counter insistence on my part to demonstrate that I could still speak in Urdu to build rapport. Contrastingly, on other occasions, my native Urdu accent made people think that I was lying about studying in the United States. To earn serious recognition in such cases, I randomly began decorating my Urdu with English, a burgher trait that always discomforted me, and hoped that the accent came out as American as possible. The language switching worked like magic, and I was allowed to begin structured interviews in Urdu. Interestingly, upper-class ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Content

- List of Tables

- A Note on Transliteration

- Acknowledgments

- 1 Introduction: Understanding Tradition, Modernity, and Class in Islamic Education

- 2 Situating the Islamic Schooling Trend in Pakistan

- 3 The Educational System in Pakistan and the Place of Islamic Schooling

- 4 Examining Diversity in Islamic Schools

- 5 Knowledge at Play

- 6 Toward a New Approach to Islamic Education

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Glossary

- Index