This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Jane Austen and the State of the Nation

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Jane Austen and the State of the Nation explores Jane Austen's references to politics and to political economics and concludes that Austen was a liberal Tory who remained consistent in her political agenda throughout her career as a novelist. Read with this historical background, Austen's books emerge as state-of-the-nation or political novels.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Jane Austen and the State of the Nation by Sheryl Craig,Kenneth A. Loparo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & European Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Juvenilia: A Liberal Conservative

National politics and political economics play a prominent role in Jane Austen’s Catharine: or the Bower, dated August 1792 and written when Jane Austen was 16 years old. The protagonist, Catharine or Kitty, lives with her aunt and guardian, Mrs. Percival, a radical Whig, who maintains that “the welfare of every Nation depends upon the virtue of it’s [sic] individuals” (MW 232), a common evangelical, radical Whig refrain at the time. Mrs. Percival’s the-sky-is-falling scenario is similar to the predictions of radical, evangelical Whigs, like Jeremy Bentham and Patrick Colquhoun, who blamed the immorality of the poor for Britain’s supposed impending economic collapse (Wilson, Making of 91–2). Moderate Whigs expressed less evangelical zeal and were considerably more hopeful of Britain’s economic survival, but to radical Mrs. Percival, the personal is definitely political, and she is appalled to think that her niece “who offends in so gross a manner against decorum & propriety is certainly hastening [the Nation’s] ruin.”

Just to stir things up a bit, Mrs. Percival’s houseguest, Mr. Stanley, is “a Member of the house of Commons” and a reactionary Tory (MW 197). Throughout Jane Austen’s lifetime, the Tory party was increasingly factionalizing into “Reactionary” and “Liberal” Tories (Lee 28), the reactionaries opposing all change and the liberals, led by Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger calling for political and economic reform. There were also, of course, moderate Tories who supported some reforms and opposed others. In Catharine: or the Bower, MP Stanley is a reactionary Tory, which, in Mrs. Percival’s house, is bound to cause trouble.

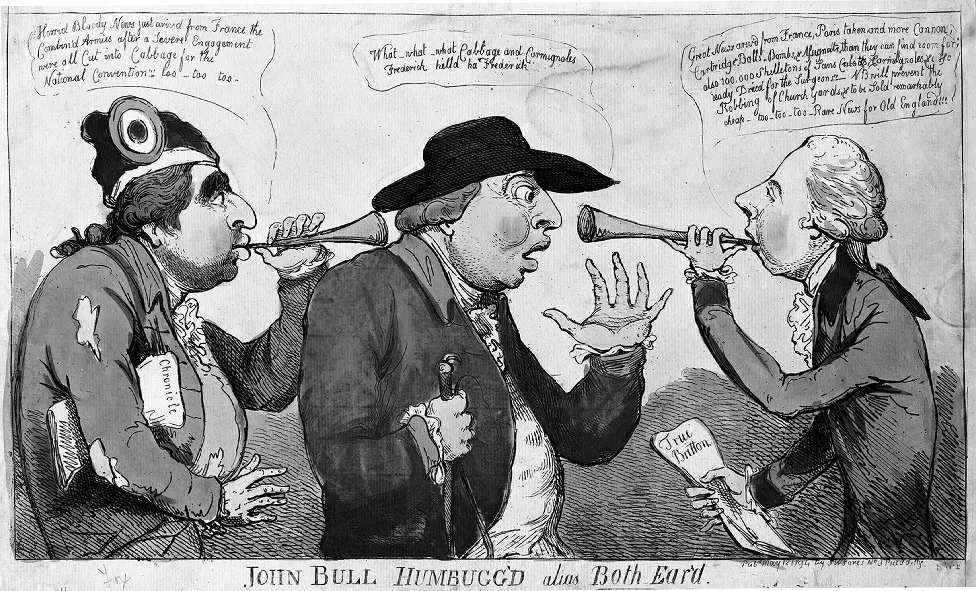

Figure 1.1 In the 1794 print above, John Bull doesn’t know what to think as Whig Opposition Leader Charles James Fox (on the left) predicts the nation’s impending doom while Tory Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger (on the right) assures him that Britain is flourishing

Source: Image courtesy of Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

Whenever Mrs. Percival and Mr. Stanley are together, they represent the two opposing, extremist viewpoints of Parliament, and they are unable to refrain from beginning “their usual conversation on Politics”:

This was a subject on which they could never agree, for Mr. Stanley who considered himself as perfectly qualified by his Seat in the House, to decide on it without hesitation, resolutely maintained that the Kingdom had not for ages been in so flourishing & prosperous a state, and Mrs. Percival with equal warmth, tho’ perhaps less argument, as vehemently asserted that the whole Nation would speedily be ruined, and everything as she expressed herself be at sixes & sevens.

(MW 212)

While Mrs. Percival provides no evidence to justify her prediction of the imminent collapse of the economy, Mr. Stanley dismisses Britain’s real and pressing problems, such as deficit spending for the war, the unprecedented national debt, high unemployment, and widespread poverty. As everyone was well aware, the flood of British immigrants to America and the transportation of petty thieves, many of them children, to Australia suggested that all was not well at home. In defending their own extreme political persuasions, Mrs. Percival and Mr. Stanley exaggerate the economic state of the nation until they both become ridiculous.

The character of Catharine or Kitty functions as the voice of reason in her thoughts and dialogue, a harbinger of intelligent and prudent characters to come, such as Sense and Sensibility’s Elinor Dashwood and Pride and Prejudice’s Elizabeth Bennet. Listening to Mrs. Percival’s and Mr. Stanley’s arguments without becoming involved in their irrational quarrel, Kitty’s calm, non-partisan attitude invites the reader to assume a similar point of view, that of the liberal Tory or moderate Whig:

It was not however unamusing to Kitty to listen to the Dispute … without taking any share in it herself, she found it very entertaining to observe the eagerness with which they both defended their opinions, and could not help thinking that Mr. Stanley would not feel more disappointed if her Aunt’s expectations were fulfilled, than her Aunt would be mortified by their failure.

The message here is plain: Political extremists lose sight of what is at stake, namely the welfare of the nation, and descend into an endless series of disputes based not on reality but on their own gross exaggerations. Mrs. Percival and Mr. Stanley MP, thus, reenact the debates in the House of Commons.

When Mr. Stanley refuses to acknowledge that problems exist, he suggests that nothing needs to be done. By insisting that the nation is doomed, Mrs. Percival implies that it is futile to attempt any intervention. Thus, both extreme political positions produce the same result – inaction – a very astute observation for a 16-year-old author. Conservative Prime Minister Arthur Balfour reached the same conclusion a century later: “conservative prejudices are rooted in a great past and liberal ones planted in an imaginary future” (qtd. in Williams 13). Balfour thus agreed with Jane Austen that, regardless of party affiliation, politicians err by ignoring the reality of the present. Balfour’s uncle, Lord Salisbury, another conservative Prime Minister, contended that the business of politicians was to effect change in the here and now: “the object of our [conservative] party is not and ought not to be simply to keep things as they are” (qtd. in Williams 12). Both Jane Austen and Tory Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger would have agreed.

According to James Edward Austen-Leigh, his aunt, Jane Austen, “probably shared the feeling of moderate Toryism which prevailed in her family” (A Memoir 71). Jane Austen’s niece, Caroline Austen, assumed likewise: “The general politics Tory – rather taken for granted I suppose, than discussed, as even my Uncles seldom talked about it” (My Aunt 173). Remaining non-confrontational about their political opinions was no doubt prudent of the Austens. Jane Austen’s father, the Reverend George Austen, was dependent on patronage for his clerical livings, as was Jane Austen’s eldest brother James, and clergymen had to remain in the good graces of their patrons, whether they were Tories or Whigs. The clerical Austens’ patrons were Tories. Because there was no separation of church and state, people’s religions usually dictated their political affiliations. The Church of England has been referred to, with some justification, as the Tory party at prayer, but Church of England evangelicals were generally Whigs, as were dissenters and non-conformists, such as Methodists and Quakers. Oxford graduates, like Jane Austen’s father, were generally Tories, and Cambridge graduates tended to be Whigs. And then, as today, there were one-issue voters.

Whig William Wilberforce championed the anti-slavery movement, and the Austen family supported the abolition of slavery; Jane Austen’s brother, Captain Francis Austen, was particularly appalled by the slave trade, which he witnessed firsthand. However, although Wilberforce was leading the attack on the slave trade, the merchants who profited from slavery and who were most vehemently opposed to the regulation of the slave trade were also Whigs. Prime Minister William Pitt and many other Tories supported the abolitionists. In this case, as in many others, a person’s party affiliation was not necessarily an indication of his position on some of the hotly debated topics of the day, and Members of Parliament voted independently whenever they felt so inclined.

Hampshire, the Austens’ home county, was staunchly and dependably Tory. First elected in 1790, William Chute was a Tory MP for Hampshire for 30 years and well known to the entire Austen family, although Jane Austen personally disliked him. Jane Austen’s brother, Edward Austen Knight, was, thanks to his adoption by wealthy relatives, a landowner in Hampshire and in Kent who became a magistrate and a High Sheriff. Although Edward was almost certainly a Tory, he showed no interest in becoming a Member of Parliament and discouraged his sons from running for political office (Honan 329).

The Austens’ cousin, Edward Cooper, was an evangelical clergyman and therefore presumably a Whig. Jane Austen found her cousin tiresome. Her sailor brothers, Francis and Charles, were dependent on Whig patronage for their naval promotions. As an officer in the militia and as a London banker, Jane Austen’s brother Henry would have been expected to have Whig sympathies. But when Henry changed careers and became a Church of England clergyman, he may have changed political parties as well. In short, the Austens had divided political loyalties, even if they were all in agreement on the issues.

Voters

At the time, a parliamentary borough could be classified as one of four types: Freeman; Scot and lot and potwalloper; Corporation; or Burgage. The most common voting districts were Freemen boroughs. There were 62 Freemen boroughs, where, in theory, any man who was 21 years old and free, that is self-employed, could vote. In practice, it wasn’t nearly so simple nor so democratic. Most Freemen boroughs restricted the number of voters in various ways, making it difficult to claim freeman status. In other Freemen boroughs, such as Liverpool, residency was not a requirement, and non-resident freemen could be enfranchised whenever it seemed necessary to guarantee the results of an election. For example, Bristol admitted 1,720 new non-resident voters in 1812 (Hammond & Hammond, Village Labourer 12).

The most democratic elections were held in the 59 Scot and lot and potwalloper boroughs. In Scot and lot boroughs, any man who paid Poor Law taxes or taxes to support his parish church could vote, but in other Scot and lot boroughs, any man not receiving welfare from the parish could vote. Voters in potwalloper boroughs were men who had families and who boiled a pot in the borough, meaning that the voter fed himself rather than eating at the table of his employer. In theory, the ability to provide for himself and his family demonstrated that the voter was not subject to another man’s influence, as voters undoubtedly were in corporation boroughs.

In the 43 Corporation boroughs, a patron served as the head of the borough, somewhat like the CEO of a company, and the other voting members of the Corporation were men who had been appointed to clerical livings, or who worked as government clerks, or who held commissions in the military, meaning all voters were indebted to the patron of the Corporation, if not entirely dependent on him, for their incomes, jobs, and promotions. In Pride and Prejudice, Mr. Collins’ groveling and flattery are suggestive of the behavior a patron could demand of his or her minions.

And then there were the 39 Burgage boroughs where only landowners voted. Their property titles ensured their right to vote, and sometimes one man owned all, or almost all, of the land in his district. For instance, Lord Radnor owned 99 of the 100 property titles in his borough (Hammond & Hammond, Village Labourer 9). The result of the borough system was that the outcome of an election was rarely in doubt. Thus, political power remained securely in the hands of the wealthy, like Mrs. Percival and Mr. Stanley in Catharine: or the Bower.

With Mrs. Percival, Mr. Stanley, and the protagonist Kitty, the reader has been shown three political options, two extreme and unacceptable positions and a third acceptable option of middle-of-the-road commonsense, but Catharine: or the Bower admits that a fourth and thoroughly contemptible choice remains, willful ignorance. As Ivor Brown notes in Jane Austen and Her World, “ignorance was bliss for those with good homes and plentiful servants” (46), and the wealthy, like Camilla Stanley, the Tory MP’s brainless daughter, could afford to be politically and economically ignorant, as long as her money held out. Camilla declares herself to be politically apathetic and proud of it: “I know nothing of Politics, and cannot bear to hear them mentioned” (MW 201). According to the petulant Camilla, still smarting over being slighted at a ball, her father “never cares about anything but Politics. If I were Mr. Pitt or the Lord Chancellor, he would take care I should not be insulted” (MW 224). Camilla fantasizes about using her father’s position as an MP to take revenge on people who irritate her: “I wish my Father would propose knocking all their Brains out, some day or other when he is in the House” (MW 204).

Although Jane Austen never finished Catharine: or the Bower in 1792, in 1809 she made alterations to the manuscript. As Claire Harman observes in Jane’s Fame, “It seems rather extraordinary that Austen was keeping this story from her teens in play at all” (50), but Jane Austen remained interested in politics, as her novels reveal, and two similar characters embodying the political extremes will reappear in Persuasion, written in 1816.

Catharine: or the Bower was not the only story in Austen’s juvenilia that depicts politics as a shamelessly self-serving business. Camilla’s assumption that political office should be used entirely for her personal advantage is echoed by another character, Tom Musgrove, in A Collection of Letters: Letter the fifth: From a Young Lady very much in love to her Freind [sic]. When Tom

Musgrove learns that his fiancé is financially dependent on her uncle and aunt, Tom “exclaimed with virulence against Uncles & Aunts; Accused the Laws of England for allowing them to possess their Estates when wanted by their Nephews and Neices [sic], and wished he were in the House of Commons, that he might reform the Legislature, & rectify all its abuses” (MW 169). Austen’s spoofing of politicians continues in another fragment with the character Lady Greville.

In A Collection of Letters, specifically Letter the third: From A young Lady in distress’d Circumstances to her freind [sic], Austen’s quick-witted protagonist Maria Williams is repeatedly humiliated by a wealthy acquaintance, Lady Greville, an earlier incarnation of Pride and Prejudice’s Lady Catherine de Bourgh. Lady Greville’s name is suggestive of the powerful Whig politician Lord Grenville, who opposed William Pitt’s attempts to expand Poor Law benefits. Lord Grenville’s argument was that the poor were beyond help, that they were ignorant, extravagant, and immoral; thus any aid they were given was sure to be money wasted, probably on alcohol. This was the same line of reasoning evangelical Whig Thomas Malthus pursued in his 1798 treatise, Essay on the Principal of Population. Jane Austen places her protagonist Maria in direct opposition to Lord Grenville’s point of view.

As a guest of Lady Greville’s, Maria braces herself for “the disagreable [sic] certainty I always have of being abused for my Poverty” (MW 157). Lady Greville notes that Maria has a new dress: “I only hope your Mother may not have distressed herself to set you off” (MW 156), assumes that Mrs. Williams can only afford the usual diet ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Chronology

- Introduction: Jane Austen’s Legacy

- 1 Juvenilia: A Liberal Conservative

- 2 Sense and Sensibility: Poor Law Reform

- 3 Pride and Prejudice: The Speenhamland System

- 4 Northanger Abbey and The Watsons: The Restriction Act

- 5 Mansfield Park: The Condition of England

- 6 Emma: William Pitt’s Utopia

- 7 Persuasion: The Post-Waterloo Crash

- 8 Sanditon: A Political Novel

- Bibliography

- Index