The pursuit of knowledge is superior to all other walks of life.

万般皆下品,唯有读书高

– WANG Zhu (汪洙)

The purpose of this book is to introduce how Chinese students adjust to an intercultural learning environment. Previous research has covered a broad spectrum of topics regarding Chinese students, including their psychological and sociocultural adjustment (Spencer-Oatey and Xiong 2006; Wang 2009; Zhao 2007; Zheng and Berry 1991), acculturation (Zheng et al. 2004), and satisfaction with their sociocultural and educational experience (Zhang and Brunton 2007). In spite of that, research particularly focusing on their academic adjustment still deserves more attention than it has received so far. Even though some research does use the term academic adjustment, it lacks a clear or scientific definition of the term and its domain (Gong and Chang 2007). Not much research has concretely probed the daily academic experience of Chinese students living in host universities, especially their classroom participation, academic performance, and learning strategies. Considering the fact that only limited research on academic-based problems of academic challenges facing international students has been conducted (Samuelowicz 1987), it is necessary to shed light on their situations and identities as international students. Thus, this book explores how Chinese students adjust academically when studying abroad at foreign universities. Moreover, how do they understand the different learning forms in their new environment and adapt to them in order to better meet academic expectations and demands?

The Growing Discussion on Chinese Students

Attention to the broad term ‘Chinese students’ has grown in the last few decades, especially with regard to investigating Chinese student characteristics. Three proposed reasons for this are: (1) excellent performance of East Asian students in international studies of achievement, (2) the increasing number of Chinese students studying overseas, and (3) the influence of China’s economic growth (Rao and Chan 2010).

Indeed, Chinese students demonstrate strong mathematical and scientific aptitude in many cross-national studies. International mathematics tests and competitions, such as the International Assessment of Educational Progress and the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (Xu, B. 2010), show that Chinese students score very competitively against their Western counterparts. Results from both the 2009 and 2012 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) also indicated that students from Shanghai successively outscored their counterparts in dozens of other countries in all PISA sections of reading, mathematics, and science (OECD 2014a).

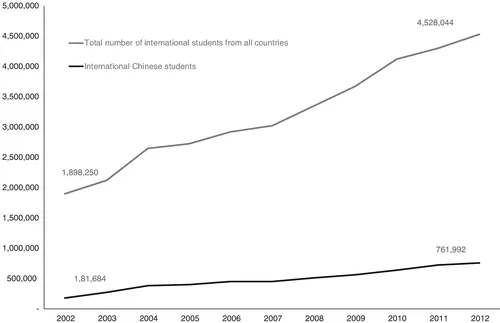

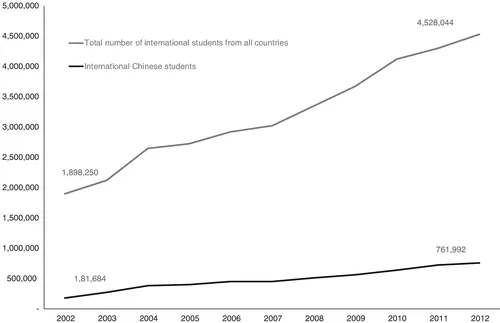

Students from China also represent the largest student group in the world to study in foreign countries. Over ten years, the number of Chinese students studying abroad has increased sharply from 181,684 in 2002 to 761,992 in 2012 (Waldmeir

2013, December 29). In 2012, 16.8 per cent of all international students enrolled for study in OECD (The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) areas came from China (OECD

2014b). According to a report from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, the rise has been particularly dramatic among middle-class families. With strong economic growth fueling a growing middle class, many Chinese families seek an alternative to the rigorous rote-based learning methods of the domestic system in China. At present, over 90 per cent of the Chinese students going abroad are self-funded (Fig.

1.1).

Internationalization of Higher Education and Increased Mobility of International Chinese Students

History of International Education: A Brief Retrospective View

Student mobility is not a new phenomenon. In fact, a large number of medieval universities in Europe were essentially international in nature (Altbach et al. 1985). The first universities founded in Paris and Bologna in the thirteenth century housed students and professors from many countries, and used Latin as a common language (Altbach and Teichler 2001, p. 6). Thus, in the beginnings of Western higher education, foreign students were the norm, not the exception (Altbach et al. 1985). It was not until the influence of the Protestant Reformation in the sixteenth century that universities began to teach in their own national languages, and internationalism became less central to university education. Still, many universities maintained international cooperation and exchanges with each other (Altbach and Teichler 2001).

In the eighteenth century, internationalization of education shifted toward what is now considered a more negative direction, as European powers began to expand their empires through colonialization. During this phase, internationalization manifested through the concerted export of education systems from European colonial powers (particularly the UK and France) to their colonies (Knight and de Wit 1995). Meanwhile, universities in the metropole served to train students from their colonies (Altbach and Teichler 2001).

After World War II, a new era of international educational exchange began, with a shift toward international relations. To achieve ‘a better understanding of the rest of the world and to maintain and even expand their sphere of influence’ (Knight and de Wit 1995, p. 8), the USA and the Soviet Union, the two superpowers that emerged from WWII, began promoting international exchange. Countries that did initiate agreements for student exchange or research cooperation did so on a relatively small scale with a diplomacy-oriented objective (Knight and de Wit 1995). These goals are still visible today in many state-sponsored exchange programs, although, in general, universities have expanded their goals to include various activities (e.g. participating in traditional study abroad programs, upgrading students’ international perspectives and skills, etc.) that raise their international profile in volume, scope, and complexity (Altbach and Knight 2007).

The First Overseas Chinese Students

China has a long history of sending students abroad for advanced knowledge. Yung Wing (容闳 or Rong Hong 1), together with Wong Foon (黄宽 or Huang Kuan) and Wong Shing (黄胜 or Huang Sheng) were the first recorded group of Chinese students in history to study overseas, setting foot in America in 1847.2 In his book My Life in China and America, Yung Wing described his journey to America, and the experience of studying at Yale College (1850–1854). Yung Wing was the first Chinese student to graduate from a US university. Benefiting from his own experience in America, he managed to persuade the Qing Dynasty government to send more young Chinese students abroad (known as the ‘Chinese Educational Mission’) when he returned. Between 1872 and 1875, the Qing Dynasty sent 120 students to the USA. These young boys were respectively placed with local families in about forty towns in the Connecticut River Valley (Hamilton 2009). By the time the program ended, more than sixty of them had attended colleges, universities, or standard technical schools. There were twenty students at Yale, eight at MIT, one at Harvard, and three at Columbia (Jin 2004, April 22). Although this plan was later abandoned in 1881, many of the students made significant contributions to China’s civil services, engineering, and sciences,3 and effectively established the now long-standing ‘modern’ tradition of Chinese students studying abroad (Levin 2004).

The ‘Reform and Opening Up’ of Study Abroad

The late Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping supported the expansion of study-abroad programs for Chinese students to travel overseas. It is worth noting that in the late 1970s and early 1980s, following the Cultural Revolution, study abroad was primarily restricted for those directly sponsored by the Chinese government. As the Chinese economic reform period progressed, the government began to relax restrictions. In 1984, the State Council (国务院 guowuyuan) issued Temporary Provisions of Going Abroad for Self-Funded Students (国务院关于自费出国留学的暂行规定 guowuyuan guanyu zifei chuguo liuxue de zanxing guiding), which required the provincial and local government to promote self-funded students to apply for overseas study and treat them as equal to government-funded students. One year later, China abolished the policy of Verifying the Qualification of Self-Funded Students Applying for Overseas Study (自费出国留学资格审核 zifei chuguo liuxue zige shenhe), signaling that China would now allow self-funded students to study abroad, with the same status and privileges as government-funded students.

Policies shifted from simply relaxing restrictions, to taking a more pro-exchange approach, beginning in the 1990s. In 1993, The Third Plenum of the Fourteenth Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (中共十四届三中全会 zhonggong shisijie sanzhong quanhui) stipulated new goals for studying abroad. Namely, the document was meant ‘to support students and scholars studying abroad, to encourage them to return to China after the completion of studies, and to guarantee them the freedom of coming and going’ (支持留学,鼓励回国,来去自由 zhichi liuxue, guli huiguo, laiqu ziyou). Ten years later, in 2003, ...