The Global Education Policy Field

While it is now commonplace for certain education policies or policy ideas to circulate widely around the world, it was not always this way. Rather, the emergence of “global education policies”—or those policies that are widely promoted by education reformers and frequently considered by policymakers—is a relatively recent phenomenon with origins in the post-World War II context. Certainly, prior to this time, there is evidence of the formal and informal study of education internationally (Sobe 2002), not to mention the dissemination of reform principles through such means as World’s Fairs (Sobe and Boven 2014) and regional and international conferences (Chabbott 1998). However, it was only in 1945, in the post-World War II context, when governments were concerned with ensuring peace, stability, and prosperity by creating multilateral institutions, that the first international intergovernmental organization with an education mandate came into being, namely UNESCO, or the United Nations Education, Science and Culture Organization (Jones and Coleman 2005).1 As Mundy et al. (2016) describe, the establishment of UNESCO, together with the development of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, placed education on the postwar agenda of multilateralism , which was focused on ensuring shared principles and values across countries.2 Importantly, these authors furthermore note that, in this context, “while education would remain predominantly the preserve of national sovereignty …, for the first time, the need for global standards and cross-national problem solving in education was recognized as an appropriate and important domain for multilateralism” (Mundy et al. 2016, p. 4).

In subsequent decades, as education became an issue of concern for more and more international organizations, these organizations represented a new aspect of international relations (Jones 2007). However, more than entities in and through which the interests of states were settled, the work of international organizations and their interaction with each other and with national and even subnational actors increasingly constituted a space—or field—of activity in its own right. In this field of activity, which has recently come to be known as the “global education policy field,” many organizations are either semi-independent or completely independent of the interests of states, with the implication being that this field is also characterized by the priorities, preferences, and autonomy of numerous kinds of actors (Jakobi 2009).

The proliferation of actors that would make up the global education policy field accelerated in the 1960s, with the breakdown of colonialism , and continued after this time, with the emergence of new states as well as new organizations that would take an interest in their education systems. These actors can be divided into at least three broad categories (Berman 1992). The first is multilateral institutions such as United Nations organizations and regional development banks. The second is national aid agencies, that is, governmental bodies that provide development assistance to low-income countries, often, though not always, along lines of national self-interest and formerly colonial relationships. The third group can be labeled international civil society and includes nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), such as philanthropic organizations, think tanks, research organizations, Save the Children , Teach for All , the Global Campaign for Education , and Education International (the global federation of teachers’ unions), to name a few. Of course, as there are uneven power relationships across organizations competing for influence (Edwards et al. forthcoming-b), and given that the field of global education policy is situated within larger geopolitical dynamics (Mundy and Verger 2015), it can be said that the “global architecture of education is … a complex web of ideas, networks of influence, policy frameworks and practices, financial arrangements, and organizational structures” (Jones 2007, p. 325).

Starting in the 1990s, in order to characterize the dynamics described above, scholars began to employ the term global governance (Mundy 2007), which can be defined as the “authoritative allocation (by a variety of means) of values in policy areas that potentially affect the world as a whole and its component parts” (Overbeek 2004, p. 2). Not surprisingly, the emergence of this term coincided with the end of the Cold War and came on the heels of a new wave of economic globalization that began in the 1970s. The point here is to note that, when it comes to the global governance of education, in the context of a world capitalist system, there have been new pressures put on states by the combination of economic liberalization , financial deregulation, and periodic recessions, together with the prevalence of the logic of neoliberalism, new public management , and accountability (Bonal 2002, 2003; Carnoy 1999; Harvey 2005; Peck and Tickell 2002; Verger et al. 2016). More specifically, these economic and ideational factors create challenges for states (a) by pressuring them to compete economically, which entails a focus on making education systems competitive (in the case of economic liberalization); (b) by making it more difficult to collect tax revenue (in the case of financial deregulation ); (c) by forcing policymakers to do more with less (in the case of periodic recessions, or in the case of budget shortfalls for other reasons); and (d) by shifting the common sense around reform such that policies based on competition and mechanistic notions of accountability are seen as being the most appropriate and desirable for improving the quality of education (in the case of logic of neoliberalism).

At the same time, politically, one can observe increasing involvement of international actors and increasing influence of globally promoted ideas in education-related affairs, both at the international and national levels. Perhaps the most prominent example is the Education for All initiative, which grew out of the World Conference on Education for All in Dakar in 1990. This conference was organized by four main, multilateral convening institutions, and the resultant education goals were agreed to by 155 countries.3 This initiative served as a key referent in the discussion around education reform in low-income countries through 2015, the date by which the six goals were to have been met (King 2007). However, it should be noted that high-income countries have not been immune to global governance dynamics. Recent examples of the global impacting the national in high-income states include the results of international tests of student achievement (Grek 2009), as well as the work of multinational corporations and consultancy companies that are “firmly embedded in the complex, intersecting networks of policy-making and policy delivery and various kinds of transaction work (brokerage and contract writing)—much of which is hidden from view” (Ball 2009, p. 89; see also Ball 2012).

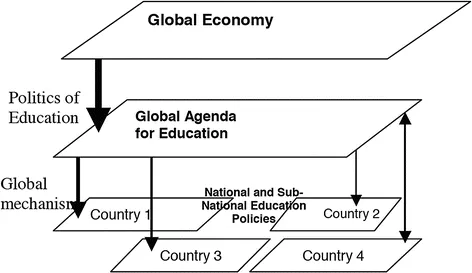

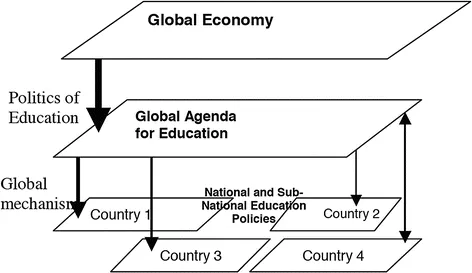

Recent work by scholars has focused explicitly on describing and theorizing the field of global education policy (e.g., Mundy et al.

2016; Verger et al.

forthcoming). The thrust of this work has been to conceptualize the “international political space in which policy agencies compete for influencing the shape of national and international education policy” (Jakobi

2009, p. 477). Visually, this space can be depicted as in Fig.

1.1.

4 A key feature of this field is that it is inhabited by the three types of international actors mentioned above—that is, multilateral institutions, foreign aid agencies, and international

NGOs—as well as national political actors, including policymakers, governmental agencies, and national and local

NGOs, among others (Lingard et al.

2015). Given the developments of recent decades, to this picture should be added a fourth group of international actors that have become increasingly involved and influential in this field—namely, transnational corporations,

consultancy companies , and

philanthropic foundations (Ball

2012). Together, these four groups are the primary actors that compete and collaborate to define and advance agendas and policies for education at the global level and to insert them into policy reform at the national level.

Although Fig. 1.1 visually places countries in a subordinate position, it is important to note that it allows for a two-way relationship between the national and international levels. As can be seen, there is a bidirectional arrow connecting country 4 with the global agenda for education. This is a crucial point,...