eBook - ePub

Inequalities During and After Transition in Central and Eastern Europe

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Inequalities During and After Transition in Central and Eastern Europe

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The book deals with the key aspects of social and economic inequalities developed during the transition of the formerly planned European economies. Particular emphasis is given to the latest years available in order to consider the effects of the global crisis started in 2008-2009.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Inequalities During and After Transition in Central and Eastern Europe by Cristiano Perugini, Fabrizio Pompei, Cristiano Perugini,Fabrizio Pompei in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economia & Economia dello sviluppo. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

EconomiaSubtopic

Economia dello sviluppo1

Income Distribution During and After Transition: A Conceptual Framework

Cristiano Perugini and Fabrizio Pompei

1 Introduction

The transformation from planned to market economies undertaken after 1989 by all new European Union members (NEUMs), former Soviet Union countries (FSU) and Western Balkans (WBs) is a fascinating, extremely complex phenomenon. Extensive market-oriented reforms were implemented in all fields, while many of the rules characterising the pre-transition society were rapidly dismissed. State influence was radically weakened in favour of market liberalisations, firm privatisations and international opening to trade and foreign investments. The whole process allowed the existing visible and hidden inequalities to develop, and new ones, associated with restructuring and vast structural change, to unfold. During the 1990s, distributional patterns in the Formerly Planned Economies evolved at quite a different pace, with inequalities reaching, and in some cases stabilising at, diversified levels after more than 20 years of transition (Aristei and Perugini, 2012). Due to the complexity of the forces into play (economic, social, political and institutional), the study of any aspect of transition is in itself a challenging task; but when distributive patterns are the focus of the analysis, the picture becomes even more intriguing and complicated. This is due not only to the fact that inequality is in itself a multifaceted concept that can then be looked at from many different and complementary perspectives, but also to the fact that basically every social, economic, structural and institutional change affects the distribution of income, either directly or indirectly. The obvious consequence of this state of facts is that a simple, formalised theoretical model of inequality during and after transition would perforce be of a restricted scope, shedding light on a limited set of aspects only, as in some otherwise valuable literature (e.g., Milanovic, 1999; Ferreira, 1999).

The aim of this chapter is to provide instead a qualitative theoretical framework to assist the understanding of the main features of the evolution of distributive pattern during transition and in the most recent years available, where possible also including the outset and the first years of the great recession of 2008. More precisely, our main focus is on income distribution in the Central and Eastern European Countries and on the Baltic Countries (CEECs and BCs, hereinafter), but wherever possible we extend our analysis to the economies of former Yugoslavia and Soviet Union. We are fully aware that taking into account only income dispersion within and between countries is not sufficient to understand the deepest structural traits of inequality. Important recent contributions (e.g., Piketty, 2014; Davies et al., 2009, 2011) show that the distribution of capital ownership (and therefore of capital incomes) is regularly more concentrated than the distribution of labour incomes. Thus, the concentration of wealth (all forms of explicit or implicit return-bearing assets, i.e., housing, land, machineries, financial capital, etc.) shapes a patrimonial capitalism that fuels large inequalities with marked features of persistence, due to the mechanisms of inheritance of wealth across generations (Piketty, 2014). However, as Milanovic (2014) points out for China, all post-communist economies of interest here can be classified as wealth-young countries, where the stock of wealth is still relatively low compared to the annual flows of income. This is related to the fact that the great transformation started to transfer property from the state to private owners only in a very recent past (early 1990s). Hence, the process of wealth concentration is still ongoing. Calculations by Davies et al. (2009, p. 56) show that wealth per capita is at the most three times larger than GDP per capita in Eastern Europe and FSU countries, whereas in the majority of developed economies the same ratio almost always exceeds five.

Bearing in mind these considerations, the following heuristic model is focused on income distribution; it is integrated and underpinned by a review of the most important theoretical and empirical literature concerning the aspects discussed. Its purpose is also – in a unified framework of analysis – to show the links, interdependencies and complementarities between the specific studies included in the chapters of the volume and to illustrate the logic underlying the sequence of individual contributions.

The chapter is structured as follows. The heuristic model is presented in Section 2, with the help of a figure in which the complex relationships between the factors in play are summarised. Then we develop the two main areas of our conceptual framework: in Section 3 we deal with the many consequences that transition as such exerted on inequality patterns, through the impact of institutional and structural change on the distribution of income between and within sources. Systemic change and the gradual entering into force of governance structures and forces typical of capitalistic economies brought into the picture the set of factors commonly recognised as the drivers of inequality in modern societies. We deal with these aspects in Section 4, where we discuss the impact of technological change and globalisation (Section 4.1), of labour and product market institutions (Section 4.2) and of the tax and transfer systems (Section 4.3). Both the discussion of systemic changes and that of the other drivers of income redistribution include a part devoted to the integration of the effects produced on inequality by the great recession that started in 2008. The transition process has indeed entailed a reshaping of the geography of foreign economic relations, which materialised into a closer integration of the Formerly Planned Economies with Western Europe and the global economy, thus increasing their vulnerability to global shocks. Section 5 summarises and provides some concluding remarks.

2 A qualitative theoretical framework for an integrated analysis of distributive patterns in transition

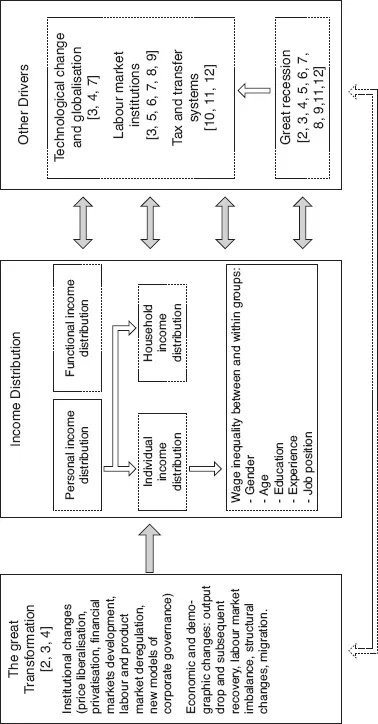

A first important aspect of studying inequality in general is that we are dealing with a multifaceted concept which can then be theoretically and empirically tackled from a range of significantly different, although interrelated, perspectives. Figure 1.1 attempts to unify in a single conceptual framework the components of overall income inequality and its several determinants in transition countries.

Every economic, structural, institutional factor has impacts on the various sides of inequality, which may differ in terms of sign and intensity. A very preliminary conceptual distinction is usually made between the study of functional and personal income distribution; as simple as it is, this distinction is of prime conceptual importance here. A large body of literature investigates the links and the interplay between these two forms and highlights how functional income distribution patterns reverberate on personal income distribution (Atkinson, 2009; Glyn, 2009; ILO, 2011; UNDP, 2013). However, we prefer to keep them conceptually separate here, in order to better clarify the role that different drivers play in shaping the levels and patterns of each of them. On the functional side, one of the inherent (and most controversial) aspects of transition was the process of privatisations and the introduction of private ownership rights, which meant that returns to capital started accruing increasingly to private economic agents (ILO, 2011; UNDP, 2013). At the same time, the transition process replaced the decisions on the allocation of added value to labour, formerly made centrally, with market mechanisms. In addition, the development of financial and securities markets offered the preconditions for capital incomes to grow in relative importance (Blecker, 2010). More generally, every facet of the institutional transformation contributed to the reshaping of the distributive patterns, directly or indirectly. Privatisations and price liberalisations, along with the macroeconomic instability that followed the collapse of the previous regime, determined the deep initial output drop and the consequent labour market imbalances. Mass unemployment suddenly came on stage, feeding important migration outflows (Kahanec and Zimmermann, 2009) while protection systems were still under construction or moving the initial steps (Milanovic, 1998). At the same time, those in employment experienced the sudden end of artificial wage compression; in one fell swoop, not only did the face of functional income distribution change dramatically, but also personal income inequality took off, posing challenges never faced before. Households had to deal with the presence of members no longer receiving labour incomes, a fact that assigned a prominent redistributive and protective function to the family and to household total income; at the same time, the dispersion of individual earnings changed dramatically, now becoming increasingly related to the overall economic conditions, emerging labour market institutional settings and individual characteristics (age, education, experience, gender).

Figure 1.1 Income inequality in transition countries: a conceptual framework

Notes: In square brackets are the numbers of the chapters in this book that deal with the topic specified.

Of course, the way transition reforms were implemented was not irrelevant in shaping inequality. The speed of transition (Aghion and Blanchard, 1994), and particularly the approach to state-owned firms’ privatisation, greatly contributed to the determination of the extent of the economic and labour market imbalances and to the emergence of profits and rents. The timing of other dimensions of institutional change – those able to mitigate these pro-inequality effects, such as competition policy or the development of financial and banking markets – shaped the net distributive outcome (Aristei and Perugini, 2014).

As soon as the mechanisms of market economies started to enter into force, other factors commonly recognised as the drivers of inequality in the capitalistic societies started to gradually gain importance and to interplay with those previously discussed.

First of all, there are forces that mainly influence the market remuneration of the factors of production, with labour earnings playing a prominent role. They are in the first instance associated with the increase of skill-premia, and include phenomena such as globalisation and technical change (e.g., Van Reenen, 2011). Overall, theories on this subject conclude that low-wage positions are associated with low-skilled or low-educated workers and higher earnings with highly educated/skilled labour supply. The predictions of the standard neoclassical Storper–Samuelson framework (for developed countries), the new trade theories (e.g., Feenstra and Hanson, 1996; Melitz, 2003; Helpman et al., 2010) (for both origin and destination countries) and the empirical evidence on firm heterogeneity and international trade (see Serti et al., 2010; Castellani et al., 2010; Helpman et al., 2012), suggest that growing internationalisation increases wage variability, through different channels. In interrelation with these conclusions, the skill-biased technical change (SBTC) hypothesis has complemented the predictions of the human capital (Becker, 1964) and the signalling/screening (Spence, 1973; Weiss, 1995) theories; it has done this by maintaining that the introduction of new technologies and the consequent organisational innovation would increase relative demand for skilled (in the sense of educated) workers, pushing their relative returns upwards (Autor and Katz, 1999). The limited capacity of these theories to explain observed inequality and labour market patterns, particularly job polarisation (Goos and Manning, 2007; Goos et al., 2009), has led to a more nuanced formulation of the SBTC theory, based on the so-called routinisation hypothesis (Autor et al., 2003). In a context such as that experienced by transition countries, that is, changing economic geography and radical structural adjustment, these factors are likely to have played an important function. The unsatisfactory results obtained from these labour demand/supply explanations led many authors to integrate them with inequality drivers related to labour market institutions (Levy and Murnane, 1992). In particular, attention focused on the drivers that favoured a weakening of wage compression mechanisms connected to the declining role of unions, collective bargaining and minimum wage provisions (Card et al., 2004; Card and DiNardo, 2002), and on the labour market reforms that increased employer bargaining power (deregulation of labour markets, proliferation and flexibilisation of new contractual options), and that introduced asymmetries in the employment protection of different categories of worker (Boeri and Garibaldi, 2007). Again, the importance of these factors during the years of labour market institutional building, and in recent years in the transition regions, is apparent.

Secondly, there are factors strictly related to systemic forces that strongly affect secondary and tertiary distribution, that is, household income after taxes, social transfers and other non-cash benefits (UNDP, 2013). Increasing trends of inequality have indeed been explained by the changes in tax and transfer systems which reduced the progressivity of the tax schedule by cutting transfers and, more importantly, the marginal tax rates for the top earners (e.g., Atkinson et al., 2011; Piketty, 2014). The implementation of new taxation systems and welfare state models as part of the transition process (Lane and Myant, 2007) and their evolution towards flat rate systems during the 2000s (OECD, 2012) suggest that these factors might have played a major role for the aspects under scrutiny here.

Lastly, in the explanation of the patterns of inequality in the most recent years, attention is given to the effects of the global crisis that blew up in 2008. The great recession impacted on all forms of inequality, asymmetrically hitting social and labour market segments, with the more disadvantaged groups of workers paying the highest bill (de Beer, 2012). However, the evolution of labour market structural and institutional features in Europe through the 1990s and 2000s considerably changed the position of the various groups of workers and their relative exposition to adverse shocks (e.g., European Commission, 2012). At the same time, the considerable str...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- 1 Income Distribution During and After Transition: A Conceptual Framework

- Part I Personal and Functional Income Distribution Patterns During Transition

- Part II Microeconomic Analysis of Income Distributions and the Role of Institutional Settings

- Part III Redistributive Preferences and Arrangements

- Index