eBook - ePub

Report on the State of the European Union

Is Europe Sustainable?

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Report on the State of the European Union

Is Europe Sustainable?

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This volume is the fourth instalment of the 'Report on the state of the European Union' series. Its shows that if the EU does not want to be ruled by crisis any longer, it must invest in sustainability, political, economic, social and environmental. Europe must turn this elusive and ever-threatening 'crisis' into a chosen and meaningful transition.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Report on the State of the European Union by E. Laurent,Kenneth A. Loparo,Kenneth A. Loparo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & International Business. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Is Governance Sustainable?

1

The Democratic Paradox of the EU

While the EU has been a driving force for the expansion of civil liberties, political rights and human rights, making Europe the most democratic continent in the world, democracy is in crisis within nation states because of the very nature of European integration that structurally relies more on output than input democracy (discussed below). The European crisis of efficiency in the course of and the aftermath of the “great recession” has logically turned into a crisis of trust with respect to the European project itself that must be fixed if Europeans want to curb the rise of anti-EU populism.

1 The democratic continent

In 2012, to the surprise of many and the consternation of some, the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to the European Union (EU), which according to the Nobel Committee, “for over six decades contributed to the advancement of peace and reconciliation, democracy and human rights in Europe.” This prize was well deserved.

There is in fact very little doubt that the enlargement of the then European Economic Community in the 1980s to Spain, Greece and Portugal and the significant enlargement to the East in 2004 and 2007 were decisive in the democratization of Europe by the European Union, as acknowledged by the Nobel Committee in their nomination: “In the 1980s, Greece, Spain and Portugal joined the EU. The introduction of democracy was a condition for their membership. The fall of the Berlin Wall made EU membership possible for several Central and Eastern European countries, thereby opening a new era in European history. The division between East and West has to a large extent been brought to an end; democracy has been strengthened.”

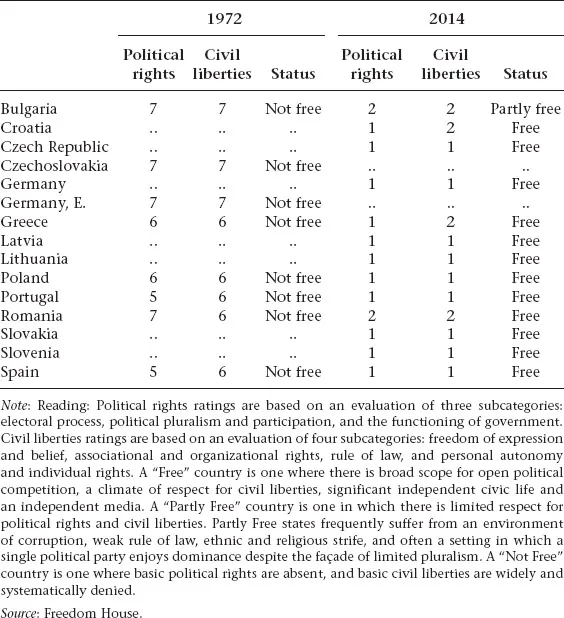

Table 1.1 The progress of democracy in Europe, 1972–2014

This democratization effort can be precisely assessed in quantitative terms thanks to the dataset of Freedom House that goes back to the early 1970s (see Table 1.1).

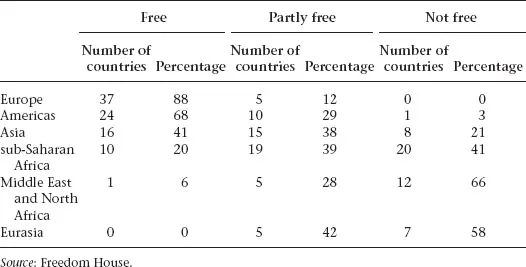

The result of this democratization is that Europe is today the most democratic continent, with close to 90% of its countries considered to be free, compared to only 70% in the Americas, 40% in Asia, 20% in sub-Saharan Africa and only 1% in the Middle East and North Africa (see Table 1.2).

Table 1.2 Freedom in Europe and other continents

2 The peculiar European democracy

Faced with the historical reality of the democratization of the European continent under the influence of the European Union in the last three to four decades, it may be hard to acknowledge that within the borders of the EEC and then the EU a conflict between “democracy” and “Europe” appeared as early as the 1970s.

The lament of a “democratic deficit” is in fact not new and was originally formulated in England in the early 1970s by Labor MP David Marquand to denounce the deepening of European integration in which no instance was directly responsible to the people. This denunciation found a resurgence in popularity following the rejection of the “European Constitution” by the French and the Dutch in the spring of 2005 (a rejection by referendum which was itself rejected by the adoption of essentially the same via parliamentary approval, fuelling even more popular resentment against the lack of accountability of European institutions).

Questioning the political nature of the new and unique system that is the European Union has fed a vast academic literature (see Wessels, 1997 for a synthesis). In strictly legal terms, European treaties provide a clear answer to the question of the nature of European citizenship and thus of the democratic quality of the European Union: European citizen are citizens of a member state belonging to the European Union. It is from national belonging that European citizenship follows, which has no independent existence. The treaty hence remains faithful to the spirit of the approach of European founding father Jean Monnet who said he wanted to unite men through states.

Two apparently consistent related sets of arguments have been developed in European studies to account for the European Union’s (EU) democratic shortcomings and unique “political system.”

The first set of arguments states that while Europe is one thing, democracy as we know it in the member states is another, and that thinking otherwise amounts to a composition fallacy. Two versions of that theorem coexist in the literature. The first one is positive: the EU is as democratic as it can be. This was forcefully presented as a “defense of the ‘democratic deficit’” by Moravcsik (2002). The second one is normative: the EU should not be democratic. It was justified in Majone (1996) by the distinction between European Pareto-improving policies and national non-Pareto-improving policies. In brief, the idea lying at the core of this reasoning is that since the EU, a non-state, is truly “new under the sun,” no past or current political criteria can be accurately used to assess its qualities, least of all those devised to evaluate qualities of national liberal democracies. According to Majone (2005), this “analogical fallacy” between national and European political regimes would be nothing less than the “most serious pitfall” threatening (s)he who studies the European Union.

The second set of arguments comes down to the idea that Europe works best without politics. Here again, two distinct ideas have been developed in the literature, embracing two historical ages of the European project. “Market Europe,” that was born out of pragmatic steps, is said to function more efficiently without the “fallacy of grand theorizing” – visions or “illusions” – and should steer clear of any conscious political integration, as undesirable as it is impossible (see Moravcsik, 2005); “Moral Europe,” an anti-power in its essence, is a grand design for the world rather than for itself, a “civilian power” heir to Christianity’s selflessness rather than Greeks’ democratic politicization. The EU raison d’être in the contemporary period would thus be to benevolently spread democracy outward, integrating as many countries as possible even at the risk of centrifugal dissolution.

Both sets of these arguments miss the economic and social power acquired by the European political regime over the years and thus the very nature of European Union democracy. The European Union is not an international organization such as the United Nations. It is not intended for peaceful coexistence and cooperation in the interest of world order by states which are members, but remain fully sovereign. It is the place of creation, application and preservation of a unique legal system that applies to the internal legal order of the member states to, if necessary, replace them. Therefore, the “European Treaties” appear improperly appointed in that they induce confusion with international treaties. They are more accurately a constitutional order, a true “European constitution,” which governs in particular the economic sphere, which was historically the first locus of sovereignty-pooling by European states.

The roots of this “European economic constitution” (see Laurent and Le Cacheux, 2006, for a detailed presentation and discussion) are to be found in the second ordo-liberal school, that of the post-war, embodied by Hayek (who, in 1962, took over the chair occupied by Walter Eucken in Freiburg). It is quite different than the original conceptions carried in the political arena by Ludwig Erhard, Minister of Economics under Chancellor Adenauer then chancellor himself, shaping the post-Nazi Germany economic system. Ordoliberalism according to Hayek proposes a more absolute view of the notion of economic constitution, as the legal means of compelling economic action of the interventionist state.

This conception was formally advanced by Kydland and Prescott (1977) and Brennan and Buchanan (1988), who aimed at developing and legitimizing, on behalf of individual freedoms and the effectiveness of public policy, an economic constitutional order constraining the state power. According to this perspective, public policies ought to be governed by principles with which the State cannot interfere. To better measure the distance between the first and second ordo-liberal schools it can be noted that in the first case, the aim is to protect the rule of law from political intervention while in the second case, the goal is to regulate government intervention by placing the “right” economic policies under constitutional protection.

The application of this logic to the European Union by the Maastricht Treaty resulted in a double bind: The national political authorities no longer had the traditional instruments of macroeconomic management or were prevented from using them, so that Europe’s institutions, in effect, supersede those of national governments, without allowing the emergence of a European government. By contrast, European institutions had the tools (currency, foreign exchange, competition policy and budgetary surveillance), but not the political legitimacy to use those tools. The result was a power-legitimacy chasm in Europe: on the one hand, power without legitimacy, on the other hand, legitimacy without power.

Furthermore, one needs to understand that the reach of the European constitution goes beyond economic policies. The separation between economic and social policy is in fact no longer that envisioned by the Treaty of Rome (1957). According to the founding text of European integration, on the one hand member states share their national sovereignty by pursuing common economic policies; on the other hand they remain absolutely sovereign in the conduct of social policies. This frontier, if it existed in the very first decades of the European integration, has become imaginary since the Single Act (1986) came partially to reality with the achievement of the Single market (1993). The gap between fiction and reality has widened in the course of the preparation and advent of the single currency. Actually, the Treaty of Rome itself explicitly aimed at this spillover of economic integration onto social policies:

Member States agree upon the need to promote improved working conditions and an improved standard of living for workers, so as to make possible their harmonisation while the improvement is being maintained.

They believe that such a development will ensue not only from the functioning of the common market, which will favour the harmonisation of social systems, but also from the procedures provided for in this Treaty and from the approximation of provisions laid down by law, regulation or administrative action.1

Because of this evolution, the efficiency of the European economic constitution becomes even more critical in shaping the relation between European citizens and European Union institutions. Scharpf (1999) has interestingly distinguished two types of legitimacy of European integration. The first one is the legitimacy through direct (or indirect) participation that he calls “input legitimacy.” The other type of legitimacy is a legitimacy of result, that is to say the collective well-being produced by European integration (“output legitimacy”).

The idea of Scharpf (1999), also found in Siedentop (2002), is that the historical and current legitimacy of European integration is based more on results than on active participation. In the name of the common good, citizens are supposed to accept their absence from the democratic process. This lack of participation becomes in the version by Majone (1996) a condition for the success of European affairs.

Because European economic and social policies are constrained by a consistent and ordered set of rules that can be thought of both positively and normatively as a constitution, and because European citizens have little power to change those rules, their efficiency is critical in the democratic viability of the European Union. The “Great Recession” triggered a crisis in European efficiency that has now turned into a crisis of political trust.

3 A crisis of efficiency turning into a crisis of trust

A sense of complacency – or worse Schadenfreude – was on display in the early months of the global crisis. Even after the brutal acceler...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction: From Crisis to Sustainability

- Part I Is Governance Sustainable?

- Part II Is the State Sustainable?

- Part III Is Inequality Sustainable?

- Part IV Is the Environment Sustainable?

- Index