This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The Future BRICS provides in depth quantitative and qualitative questions and answers about the future of the BRICS Forum as a synergistic economic alliance and is a valuable resource for anyone interested in the ongoing international debate about the economic future and sustainability of the emerging markets in general.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Future BRICS by R. Marino in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Macroeconomics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

BRICS Forum: an Overview

1

Introduction

BRICS is more than an acronym. It’s the official title of a structured economic association of five high-profile emerging market economies: Brazil, Russia, India, China and now South Africa. Each nation has its particular strengths along with its particular weaknesses, but in the case of the BRICS as one economic entity, the original purpose of the alliance is that each country’s strengths will become stronger and their weaknesses will diminish.

Beginning with the first formal BRIC summit in Yekaterinburg, Russia on 16 May 2008, an official summit is held each year and the summits are attended by each nation’s head of state. In the first summit, discussions focused primarily on global economic conditions and opportunities for growth. Each country agreed that cooperation among the four was a distinct global economic advantage. At the end of 2010, South Africa became a full member of the BRIC extending the alliance and the acronym to the BRICS. The BRICS Forum was officially organized in 2011. The Forum is an independent organization of the BRICS countries which encourages economic, cultural and political cooperation among the BRICS nations. BRICS economic treaties on tariffs were established along with an international political alignment in terms of global affairs. Of particular importance is the macroeconomic reach of the BRICS. With a total estimated 2012 GDP of roughly $15 trillion, based on the official exchange rates, the BRICS nations are not far behind the United States, whose GDP is $15.6 trillion.

Chapter 3 of this book looks at the upcoming regulatory changes, mainly Basel III, and is entitled ‘Basel III in Conjunction with Nation-Specific Regulatory Measures’. This is an important subject for the book’s thesis. In order for us to determine if the future BRICS is a synergistic economic alliance or business as usual, we need to engage all possibilities of future capital flows. This chapter in particular enunciates the reduction of capital available from the global banking system for capital flows, especially for the emerging market economies that are heavily dependent on foreign capital inflows to finance their above-average GDP growth rates. From a technical perspective, to determine the exact reduction in capital unavailable from the global banking system is an extremely difficult if not impossible task due to the ever expanding money supply of the advanced economies, but nonetheless as students of the global economy it’s imperative that we fully understand the negative future effects of increased regulation, most notably Basel III, relative to a reduction of future global capital flows throughout the phase-in Basel III period from 2013 to 2019.

Ironically, the collapse of the Bretton Woods consensus in 1973 set the stage for a dramatic increase in contemporary financial globalization of the developed nations which ushered in the contagions and crises of the 1990s and laid the foundation for the subprime debacle and the Great Recession of 2008. With that said, the collapse of Bretton Woods undoubtedly produced a more elastic world economy which included the formidable growth of the emerging markets. The free flow of capital from the developed world into the emerging markets was relatively low in the mid- to late 1970s, but the global financial world witnessed a healthy increase of free-flowing capital to the emerging markets in the 1980s through to the mid-1990s. However in 1997, there was definitely a setback due to the Russian and Asian financial crises, but it should also be noted that, beginning in 1997, there was an inordinate increase of private capital flows to those countries: foreign direct investment (FDI).

Beginning in the 1990s, the emerging markets in general became synonymous with staggering GDP growth rates which obviously spawned a greater need for capital funds. World financial intermediaries, such as mutual funds, pension funds and insurance company funds, worked their way into the emerging markets’ financial systems through international banks to capitalize on the exceptional growth rates. Moreover, the emerging markets were able to generate additional capital in the American markets with the creation of their own American Depository Receipts (ADRs) which trade on the American exchanges and also the Global Depository Receipts (GDRs) which trade on any number of world exchanges.

China in 2007 received $190 billion in net private capital flows. The estimate for net private capital flows to China in 2012 is approximately $250 billion. In 2007, India received roughly $100 billion in net private capital flows. The 2011 estimate for 2012 is around $90 billion. Brazil in 2007 was the recipient of roughly $100 billion in net private capital flows and the 2012 estimate for net private capital flows to Brazil is between $135 and $140 billion. Now to a more checkered scenario: Russia in 2007 received roughly $200 billion in net private capital flows, only to see that number plummet to approximately $75 billion in 2008 followed by an even further decline in 2009 to almost flat. However, the estimate for Russia’s net private capital flows for 2010 is almost $50 billion, but this amount is the precursor to the $100 billion per year estimate for years 2011 and 2012.1

The future success or failure of the BRICS as an economic alliance will depend on the answer to this question: why has the increase in upcoming global financial regulations underscored by sluggish GDP growth in the US, the Eurozone and Japan restricted capital flows to the emerging markets resulting in lower future growth rates for the BRICS?

This is an important question because at this point in time we really don’t know. For one thing, the lag time between the complete implementation of the new international financial reserve requirements (Basel III) and the actual culminating effects among the global BRICS is too great. As of this writing, a number of concerns are beginning to surface from the BRICS countries with regard to fundamental GDP growth, for example, huge capital outflows, civil discontent, inflation, deflation, unemployment, wealth distribution, and so on. These factors will obviously vary from country to country, but a so-called better-than-expected current GDP growth rate from an emerging market is not in and of itself a prediction of sustained future growth if the global financial markets are constrained.2

This book will bridge the gap between the staggering growth rates of the BRICS over the past ten years and the BRICS’ forecasted growth rates for the next ten years. It will serve as a valuable resource for the world academic community in general and for anyone in particular who may have an interest in the long-term future growth prospects of the BRICS in conjunction with the success or failure of their economic alliance, the BRICS Forum. This book will also be an important resource for any government, legal or business organization that may have a vested or unvested interest in the success or failure of the future growth of the BRICS and the emerging markets in general relative to the past, present and future growth rates of the advanced economies.

Chapter 2 will focus on the BRICS Forum as an economic and global political alliance. This chapter in particular sets the stage in analyzing the BRICS Forum as a synergistic economic alliance where all participants benefit equally – or are there unequal factors among the five nations which tilt the alliance in favour of one country or another at the expense of the rest, making the economic alliance business as usual?

Chapter 3 extensively addresses the Basel Accords in general and most specifically Basel III, but it’s important to note that due to the role of regulation within the global economic spectrum, Basel III will be analyzed in conjunction with nation-specific regulatory measures – most notably the US, the EU, the UK and Switzerland. For our purposes, we will discuss the Basel Accords and Basel III both in conjunction with nation-specific measures and in terms of its ramifications on the world banking system. The Basel Accords and Basel III establish the world’s uniform bank reserve requirements. It’s important that the reader grasp the regulatory reserve requirements of Basel III in conjunction with its phased-in implementation timetable (2014–19). Chapters 4 to 8 will analyze the overall macroeconomics of each BRICS nation in relation to its position as a high-profile emerging market economy past and present, but more importantly the analysis will highlight the macro-economy of each BRICS nation relative to its peers within the BRICS Forum. Chapter 9 will analyze and forecast the BRICS GDP projection for 2013–15. In Chapter 10, we arrive at a conclusion. In this effort, we will answer two pivotal questions with regard to the success or failure of the BRICS Forum: (i) why has the increase in upcoming global financial regulations underscored by sluggish GDP growth in the US, the Eurozone and Japan restricted capital flows to the emerging markets resulting in lower future growth rates for the BRICS; and (ii) the BRICS future – a synergistic economic alliance or business as usual?

In 2013, the BRICS GDP forecasts underwent a significant reversal accompanied by a substantial rotation of capital outflows especially in Brazil, India and South Africa. In an interview on 7 July 2013 IMF Managing Director Christine Lagarde said that the IMF’s global growth forecast for this year would be scaled back this week – and emerging market economies were to blame. ‘We had a growth forecast of about 3.3%,’ Ms Lagarde said, referring to the fund’s forecast for this year. ‘But I fear that considering what we are seeing now in emerging countries in particular – not developing countries and low-income countries but emerging countries – I fear that we might be slightly below that,’ she told an economists’ conference in the southern French city of Aix-en-Provence.3

In April 2013, the IMF had cut its 2013 global growth forecast to 3.3 per cent, down from its January estimate of 3.5 per cent. For South Africa in particular, the revision in growth estimates is extremely disappointing. South Africa’s entrée into the BRICS economic alliance was underscored by hopes that the economic alliance would help bridge the gap in South African exports due to a prolonged slowdown in European economic activity. Moreover, the recent IMF growth revisions work in tandem with the World Bank Global Economic Prospects report which claims that ‘the growth rates of BRICS member have long been overstated’.4 The report argues that inflation problems continue to worsen in conjunction with deteriorating current account balances which are a clear indication that the BRICS countries are unable to maintain rapid growth momentum without increases in prices. ‘The report blames domestic supply bottlenecks – arising from weak or poorly enforced regulations, corruption, inadequate or irregular provision of electricity, or inadequate educational and health investment – for the price pressures.’5

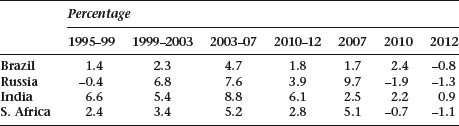

In light of its latest BRICS revisions, the IMF will probably upgrade other forecasts, particularly in the United Kingdom where the IMF and the UK Treasury have publicly disagreed with each other over monetary and fiscal policies. In all likelihood in the case of the UK, the IMF will probably increase its growth forecast from 0.7 per cent to 1 per cent. In April 2013, IMF chief economist Olivier Blanchard warned Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne he was ‘playing with fire’ and should ‘consider adjustment to the original fiscal plans’. The IMF had expected the world economy to grow 3.3 per cent in 2013 and 4 per cent in 2014, with corresponding growth of 1.2 per cent and 2.2 per cent in the advanced economies, and 5.3 per cent and 5.7 per cent in emerging economies. The IMF’s latest World Economic Outlook report, from April, forecasts a growth rate of 2.8 per cent for South Africa this year, rising slightly to only 3.3 per cent next year, owing to sluggish mining production and weakened demand from the Eurozone, which remains a key export market for the country (see Table 1.1).6

Table 1.1 Growth post-crisis has been much weaker than pre-crisis: BRICS without China

Source: Based on data collected from International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook, April, 2013.

The year 2013 seems to have been something of a turning point for the BRICS nations in terms of its illustrious economic history. Numerous financial news headlines and lengthy articles inside the BRICS countries have begun to surface, for example:

BRICS a force but cannot challenge US due to disputes

Though BRICS has emerged as a dynamic emerging economic market group with its plan to set up a development bank, it would be ‘unrealistic’ to expect the grouping to challenge US hegemony as the member nations face many hurdles, including territorial disputes, preventing them from deeper cooperation.7

The above headline is part of an article which was originally published in Beijing and written by Chu Zhaogen, a Chinese scholar. On 2 April 2013 it was picked up and published by the Economic Times of India.8 Moreover, the article was originally titled: ‘BRICS a force despite ifs and buts’. According to Zhaogen, ‘It is unrealistic to expect Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (BRICS) to become a center of power that can break the existing world order, which is marked by Western dominance and US hegemony.’9

In order for the reader to fully appreciate the BRICS as an economic alliance, we need to take a step back and try to understand its geographical disparities. Each BRICS nation is a regional power, but history has put each of them in precarious situations in terms of territorial or political disputes. For example, as of this writing Russia is in an ongoing disagreement with Chechnya while simultaneously trying to come to terms with its pro-US neighbours. On the other hand for years, China has had territorial disputes with India, Japan and a number of Southeast Asian countries. Moreover, India has historically had ongoing territorial disputes with Pakistan and China, and in the same vein, Brazil is very wary of Argentina. Plus it is important to remember that China shares its borders with Russia and India. From a political perspective that can be somewhat problematic for the Chinese and the Indian authorities as well. Here recently, tensions have increased in the China–India relationship over China’s objections to India’s enhanced nuclear programme.

An interesting side-note took place in March 2013 at the annual BRICS Forum meeting which was held in Durban, South Africa. The BRICS Forum officially announced the formation of its own development bank which in essence would rival the World Bank. Needless to say, this came as a complete surprise to the world economic community and from the outset was widely regarded with enormous scepticism. The BRICS Development Bank is still at least four to five years from inception and there are a number of inter-BRICS issues that have to be resolved.

Se...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Part I BRICS Forum: an Overview

- Part II Basel Accords

- Part III BRICS Macroeconomics

- Part IV Conclusions

- Notes

- Index