eBook - ePub

Britain and the Olympic Games, 1908-1920

Perspectives on Participation and Identity

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Britain and the Olympic Games, 1908-1920 focuses upon the presentation and descriptions of identity that are presented through the depictions of the Olympics in the national press. This book breaks Britain down into its four nations and presents the debates that were present within their national press.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Britain and the Olympic Games, 1908-1920 by Luke J. Harris in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Social History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The 1908 London Olympics

The fourth Olympic Games took place in London, England, between 27 April and 31 October 1908, a period of just over six months, making these the longest of the 30 modern Olympic Games. Twenty-two nations sent athletes to compete, and in total just over 2000 athletes participated. Twenty of these nations had competed in at least one of the three previous Olympics, although there were two nations competing for the first time; Finland and Turkey. Athletes from New Zealand were also competing for the first time since they were part of an Australasian team. The athletes competed across 23 sports and 110 events, which ‘not only made the 1908 Games the largest Olympics to date, but also the largest international sports gathering ever staged.’1

The athletes that featured in the top three positions were the first in Olympic history to receive the gold, silver and bronze medals that are today synonymous with the Olympic Games. The medals featured a naked male being crowned with a laurel wreath by two women and measured just 34 mm in diameter.

The sporting events began with indoor tennis in late April, and concluded with association football, rugby union, boxing and lacrosse, which took place between 19 and 31 October 1908 (the same date that the Franco-British Exhibition, which was held upon the same site, concluded). The athletics events, the centrepiece of The Games, took place between 13 and 25 July 1908.

The fourth Olympic Games had been awarded to Britain with just 17 months’ warning as Rome had been scheduled to host them but dropped out following financial problems after the eruption of Mount Vesuvius.2 The manner by which the British were given the Olympics ‘offered a chance to show British organising ability and established an appropriate relationship with the IOC [International Olympic Committee] which gave the British plenty of leverage in policy matters.’3 The authority by which the British took control of the Olympics was demonstrated by the international rules that their sporting associations established for those sports without such rules. The British also insisted that only British judges would officiate to ensure fair play, moves that also indicated British belief in her sporting hegemony.

The majority of the events took place in the first ever specially constructed Olympic Stadium. Known as ‘The Stadium,’ ‘The Great Stadium’ or the ‘White City Stadium,’ it was located in Shepherd’s Bush, west London and alongside the site of the Franco-British Exhibition that was also taking place in the summer of 1908. The exhibition itself was a great success, attracting 8.5 million visitors between May and October. As well as The Stadium the other Olympic locations were; Queen’s Club, Kensington (indoor and real tennis), Hurlingham Club, Fulham (polo), Prince’s Skating Club, Knightsbridge (figure skating), Northampton Institute, Knightsbridge (boxing), All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club, Wimbledon (lawn tennis) and Uxendon School shooting club (clay pigeon shooting).

The stadium was so vast that inside the 440 yards athletics track there was room for a 50-yard swimming pool, diving board, rugby/football sized pitch and outside of it was a cycling track measuring 660 yards. As Britain had only a short time to prepare, the Stadium was assembled in just ten months by George Wimpey and could hold up to 90,000 spectators.

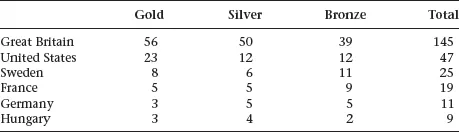

The opening ceremony took place on 13 July 1908 to signal the commencement of the athletic events, with King Edward VII in attendance. On the first Sunday of The Games, a religious service took place in which the Bishop of Pennsylvania gave a sermon where he stated, ‘the important thing in these Olympiads is not to win, but to take part,’ – a statement that has become synonymous with the Olympics. Hosts Great Britain dominated The Games in terms of total competitors and medals won. Britain provided nearly 700 athletes (36 per cent of those competing)4 and consequently won 146 medals, as is illustrated in Table 1.1. As will be discussed in detail throughout the following pages, the majority of these victories occurred in the non-athletic events such as boxing, rowing, sailing and tennis (where Britain won every gold medal on offer at Wimbledon). Only British men entered the racquets competition, and polo was competed solely between teams from Britain and Ireland.

Table 1.1 Medal table from the 1908 Olympics

Source: Llewellyn, 2011, p. 683.

The athletics contests saw numerous controversies between hosts Britain and the United States, principally the 400 metres and tug-of-war events. Such was the displeasure of the American officials that they produced a booklet called Tirade of criticism5, which detailed their criticisms. Britain constructed its own response to this, Replies to criticisms of the Olympic games. Controversy also occurred in track cycling, when after the 1 kilometre event there were no medals handed out. David Miller explains the reason for this; ‘Of the four finalists, Ben Jones and Clarence Kingsbury of Britain suffered punctures, while Maurice Schilles of France and Victor Johnson (Great Britain) adopted such delaying tactics, finishing outside the time limit, the race was declared void.’6

Organising the British team

During the nineteenth century, Britain had been the driving force behind the formal organisation of many modern sports. It was her sporting associations that created formalised rules and aided sports’ global spread. An outcome of this was that the nations’ of Britain played each other in many of the first international sporting contests. A prime example of this was the first international football match that took place between Scotland and England in November 1872. The match ended goalless, but it was the first of many matches between the two teams, and these refuelled the age old rivalries between the peoples of Britain. Richard Holt states, ‘national difference was the very stuff of sport’7 and;

‘Scottishness’ and ‘Welshness’ were constantly fed by a sense of antagonism towards the English as the politically and economically dominant force. Sport acted as a vitally important channel for this sense of collective resentment, which was the nearest either people came to a popular national consciousness.8

International sporting matches began during a time that historians believe the identities of the nations of Britain were changing. This primarily concerned the change and loss of their own individual national identities via industrialisation and their role in the British Empire.9 Paul Ward comments upon British identity and masculinity at this time, ‘Man’s ultimate function was constructed as the conquest, extension and defence of the “Greater Britain” of the Empire. The “new imperialism” of the late nineteenth century was accompanied by a reconstruction of the central tenets of masculinity, from moral earnestness and religiosity to athleticism and patriotism. In such a way the nation and maleness became entwined.’10

When it was announced that for the 1896 Athens Olympics one team would represent England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales it brought about a new sporting concept, as previously the four nations had competed individually. Twelve years later, the concept was still an unusual one, as, apart from in Davis Cup tennis competition, which had begun in 1900 as a contest between Great Britain and the United States of America, the nations of Britain competed separately in sport. The custom of the British nations competing separately may explain why some of the Scottish and Irish sporting associations desired to have their own national team for the 1908 Olympics,11 rather than for any nationalist desires. The possibility of the British nations competing separately at the 1908 Olympics had been quashed at the 1907 IOC Conference, as this meeting determined that a ‘country’ is ‘any territory under one and the same sovereign jurisdiction.’12 This ensured that ‘Great Britain and Ireland’ would have just one team at the London Olympics. The British Olympic Association (BOA) was formed in 1905.

In the three Olympics Games prior to 1905, English sporting associations had organised British participation, for example, the Amateur Athletic Association (AAA) had arranged the British athletics team for the 1900 Games.13 The formation of the BOA saw the inclusion of the Scottish, Irish and Welsh sporting associations in the Council, but often the English Associations dominated. This was the case in swimming, where the selection board comprised three English officials and only one official from each of the other three nations.14

The length of the 1908 Olympics, combined with the lack of international interest in some events, ensured that Britain entered more than one team in some sports. For example in the tug-of-war, three teams represented England (to create a five team competition,)15 and in hockey, each of the British nations had their own team (to make a six team competition).16 The British teams in both of these events competed under the name of ‘Great Britain and Ireland’, and ensured that Britain won all of the medals on offer. The Football Association (of England) also made similar plans for their sports competition, but these plans fell through because of a lack of support from the other national associations.17 The result was that just one British team, comprised solely of English amateurs, competed. This side was captained by Tottenham Hotspurs’ Vivian Woodward and, after victories over Sweden and the Netherlands, they faced Denmark in the final, winning by two goals to nil to take the gold medal.

The belief in superiority of British culture

The growth and prosperity of the British Empire had given the British people a sense of superiority, both physically and culturally.18 Charles Darwin’s various works had a major impact upon this feeling, as described by David W Brown; ‘throughout the English-speaking world, philosophers, politicians and militarists now considered wider social ideas and issues from a Darwinian standpoint.’19 At the start of the twentieth century, some people began to question if British superiority had diminished and international sporting defeats were one area that contributed to this feeling.

Sport was a central element to British identity at the end of the nineteenth and start of the twentieth centuries. Mike Huggins comments that ‘the games ethic and athleticism variously became a cultural bond, a moral metaphor and potent symbol of British power.’20 Success in sporting contests was an expectation, and the inevitable defeats led to dismay. A prime example of the sadness of defeat was demonstrated after England’s first home cricket defeat. Cricket had established itself as England’s national game in the late nineteenth century and enjoyed a strong cross class following. After the eight run defeat to Australia in London in 1882, The Sporting Times published an obituary to ‘English cricket, which died at the Oval on 29th August, 1882,’21 leading to the creation of one of the world’s famous of sporting contests ‘The Ashes’. The growth of sports across the world, particularly across the British Empire and North America, gave Britain previously unprecedented competition. Consequently, defeats occurred and this dented the British belief in her sporting superiority.

One of the most damaging defeats to Britain’s spo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- The Olympic Games, 1896–1920

- Introduction

- 1 The 1908 London Olympics

- 2 The Perspective of the 1908 Olympics in the Nations of Britain

- 3 Preparing for the 1912 Olympics

- 4 The Stockholm 1912 Olympics

- 5 The Perspective of the 1912 Olympics in the Nations of Britain

- 6 Preparing for the 1916 Olympic Games

- 7 The Attitude of Britain towards the Olympic Games in 1919

- 8 British Preparations for the 1920 Olympics

- 9 The 1920 Antwerp Olympics

- 10 The Perspective of the 1920 Olympics in the Nations of Britain

- Conclusions

- Appendix

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index