![]()

1

Foreign Language Education in America

Steven Berbeco

Introduction

There is a story that was recently in common circulation among high school Arabic teachers of an experienced and successful teacher who placed before himself an unusual challenge. He had traveled to many countries in the Middle East to collect materials; his students consistently rated him as a strong teacher; the standardized test results from his classes were surprisingly high for the school’s demographics; he had even developed a curriculum that was published commercially. In short, here was a solid teacher of a highly challenging language. And, to test his aptitude for teaching foreign languages, he decided to teach Arabic to his cat.

This seemed like it would present some difficulties, but the teacher was sure that he would be able to overcome any obstacles. After all, he had authentic materials from the Middle East, a curriculum that was regarded highly by his peers, and years of classroom experience. The teacher also had a graduate degree in education and was fully credentialed by the state’s teacher licensure agency. His cat was good-natured, seemed eager to please, and was attentive for the most part – and in any case the cat paid greater attention than some of the teacher’s high school students.

Not surprisingly, this was not a successful endeavor. The cat got bored and wandered off.

Teaching a foreign language appeared deceptively unproblematic to this teacher. The premise is simple enough: introduce new words for what students already know. Instead of a dog, it’s now a perro, chien, kelb depending on whether your students are there for Spanish, French, or Arabic. But the words themselves carry meaning within a student’s frame of reference, so much so that a picture of even the most benign kelb can send a student scurrying for cover under a sofa.

This story circulates mostly in teacher training workshops, and not as a cautionary tale about teaching one’s pets. The story is used to demonstrate that teaching is more than just the subject matter and the person in the front of the room. When teachers forget about the context of the class, when they make assumptions about their students and the learning setting, then they may find themselves in as ridiculous a situation as trying to teach Arabic to a cat. In these cases, it does not really matter what the teacher says: it’s all just babble.

The problem of linguistic confusion traditionally has its origin with the Biblical account of the Tower of Babel as told in Genesis 11. The people of Shinar decide to build a tower that reaches to the heavens, and God confounds their efforts by muddling the language that they speak. As a result, the people can no longer understand each other: they stop building the city and scatter themselves across the world.

The Tower of Babel may be interpreted in more than a few ways. Perhaps the most common is as an allegory of divine punishment for human conceit and hubris. Others may look at it as unambiguous evidence in support of their efforts to discover or discern the original language of mankind (Eco, 1995). In popular culture, it is often assumed as an explanation for why we don’t all speak the same language, that is to say, a problem that is as old as the Bible.

There is another interpretation of the story of the Tower of Babel, one that is relevant to the cat-teaching teacher. The narrative is clear about the confusion of languages, but perhaps can be expanded for our purposes to include a confusion of the teaching of languages. The builders of this tower all had the same lofty goal, and they were ultimately thwarted by their inability to communicate a shared interest in continuing the tower’s construction to completion. On a smaller scale, the teacher and cat may have had common goals but, like the workers of Shinar, they could not express this to each other.

The central notion of Foreign Language Education in America follows a similar argument, and suggests that the field of foreign language education may suffer from a comparable disorder. Practitioners, researchers, administrators, students, and other stakeholders want to improve the quantity and quality of language learning in the United States, but by and large we have not been cooperating in unison as effectively or efficiently as we might. Possible reasons for this lack of coordination may include the diverse customs and routines of each subfield, the conferences that aren’t promoted widely, or the jobs that are advertised always in the same places.

However it is also possible that we simply don’t understand each other. As the following chapters demonstrate, the styles of writing and discourse change from middle school to university to community college to the military. The narrative from one contributor may be an anecdotal account of a teacher’s experience, whereas another contributor may present statistical outcomes of a program. A chapter may support its arguments by tracking changes over the past century, and yet another may bring the reader to the immediate and detailed present-day experience of the students. This is evidence of different approaches to the same problem – how to teach a foreign language – and not a lack of success on the part of one or another educator to adhere to a consistent method of presentation and analysis.

It may be that we sometimes fail to recognize that, as language educators, we are all dialects of the same original language.

Building the tower1

Pressures outside of the foreign language field also promote the divergent approaches to language teaching. Our country’s record of second language instruction – specifically, non-English languages to English speakers – follows the ebb and flow of greater social and political forces more than any single development in pedagogy or local educational policy (Chastain, 1980; Pavlenko, 2003). In particular, foreign language education is sometimes jerked quickly in a new direction because of world events.

Americans would like to assume that no one would argue against the importance of foreign language education, and clearly we benefit as a country from knowing more about our neighbors (Baroudi, 2007). Yet we do not see the steady increase in foreign language education that these assumptions would presume. ‘Languages, like fall and spring fashions, … rise or fall in the marketplace, usually on the whim of some congressman or other, or some self-proclaimed language expert in the State Department’ (Girouard, 1980). As a recent example, college foreign language course enrollments have fallen in 2015 for the first time in twenty years (Goldberg et al., 2015).

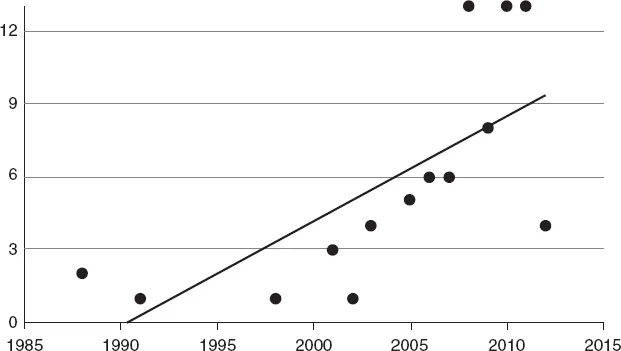

Languages are introduced to the schools as our nation looks outward to its neighbors, and then languages are pulled from the districts as we become more suspicious even of those same neighbors. For example, college student enrollment in Arabic has held low but steady as compared to the overall modern foreign language enrollment until 2002 when it began a meteoric rise (Brod & Huber, 1990; Furman et al., 2007, 2009). Similarly, the number of colleges offering Arabic instruction has nearly doubled, from 264 in 2002 to 466 in 2006 (Furman et al., 2007), a trend that is similar to the rate of elementary, middle, and high school Arabic programs that have been established in public and public charter schools (Doffing et al., 2013; see Figure 1.1).

However, there was a different reaction in Mansfield, Texas when the public schools began development of Arabic classes with the support of a $1.3 million federal grant. News outlets reported residents’ significant concern and local politicians called it an ‘atrocity’ and a ‘decided effort to suppress the history of our own country’ (Knight, 2011). Curriculum development was slowed in response and then eventually halted altogether because of strong political and community opposition.

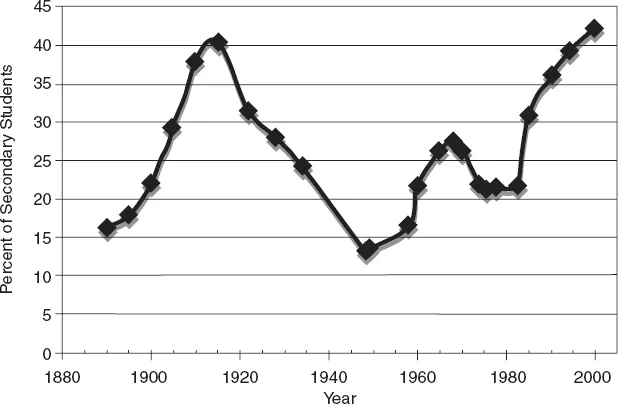

American students feel this loss as their classroom experiences wax and wane in diversity, buffeted by greater socioeconomic forces that drive our national identity (Lantolf & Sunderman, 2001). Figure 1.2 demonstrates the vicissitudes of secondary student enrollment in modern languages (Parker, 1954; Enrollment in Foreign Language Courses, 2007).

Foreign language study started in earnest in secondary schools as the common model of school moved from the elite Latin grammar schools to church-sponsored academies, with the greatest changes coming in the later comprehensive high schools (Reese, 2005). Change was slow; although Latin has been offered continuously since the first grammar schools, modern languages were not widely introduced until the mid-1800s. Classical languages like Latin and Ancient Greek were taught for theological reasons, as well as for the mental training associated with their study, and so modern languages were first introduced – and in some cases are still taught – using the ‘grammar-translation’ method that treats languages as logical objects that can be manipulated but not actively spoken. For example, early support for teaching French and German argued that French should be taught as a gateway to understanding moral reasoning, and German as a means of grasping logic (Du Pont, 1923, pp. 59–63).

Figure 1.1 Number of K-12 Arabic programs established by year

Figure 1.2 Enrollment in modern languages

The grammar-translation method builds students’ skills in translating a written text, rather than understanding and producing spoken and written language. This method is the baseline of modern foreign language education and all pedagogy and curriculum development in the past century can be viewed as expressing tacit conformity with, or loud reaction to, this method and its principles (Byram, 2001, pp. 505–506).

The period between the Civil War and the First World War saw significant changes for public education in general as well as the growth of the comprehensive high school. A Michigan Supreme Court ruling in 1874 established the legal precedent of using property taxes to support public education, laying the economic and legal groundwork for the rapid growth of secondary schools in several states. A year later, Harvard University was the first college to set the study of a foreign language as a graduation requirement; this has become a widespread expectation at the college level, prompting secondary schools to introduce foreign languages in order to help their students place into college. In the following decade Powell v. Board of Education (1881) ruled that foreign languages cannot be prohibited from public schools in Illinois, a clarification of the 1845 School Law that declared English as the official language of instruction for the state (Baron, 1992, p. 188).

During this time period, the most popular foreign language was German, most likely because of the strong German immigrant communities in the Midwest as well as the common perception that German was a more rigorous language – and so similar in a way to studying a modernized Latin – than French or Spanish, the two next-most popular languages in secondary schools at the time. While overall immigration was increasing during this time period, German immigration in particular represented about a quarter of all immigration (Figure 1.3), second only to Irish in numbers. Irish immigrants typically spoke English, so German was a natural and popular candidate for foreign language study (German Immigration Since 1820, n.d.).

German immigrants were spread throughout United States, but mostly concentrated in northern Midwest states like Wisconsin and Minnesota (Schlossman, 1983). Today, more Americans report German ancestry than any other ethnic group (US Census Bureau, 2004, p. 2). German-Americans had a profound effect on America’s elementary education system. A German immigrant to Wisconsin and student of Froebel’s theory of cognitive development opened America’s first (German-language) kindergarten, later training a teacher who moved to Boston and ope...