eBook - ePub

A Business History of the Swatch Group

The Rebirth of Swiss Watchmaking and the Globalization of the Luxury Industry

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Business History of the Swatch Group

The Rebirth of Swiss Watchmaking and the Globalization of the Luxury Industry

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book offers a detailed and full analysis of the strategy which enabled the Swatch Group to establish itself on the world market. In particular, it tackles the issues of production restructuring, with the opening of subsidiaries in Asia, and the implementation of a new marketing strategy, characterized by the move towards luxury.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access A Business History of the Swatch Group by P. Donzé in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Management. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

People were virtually writing the Swiss watchmaking industry off in the early 1980s, as it had not managed to contain the worldwide expansion of it’s Japanese competitors. Powered by the mass production of first high-quality mechanical watches, then quartz watches, the Japanese watchmaking industry launched a growth policy in the second half of the 1960s in a bid to challenge Swiss domination of world markets.1

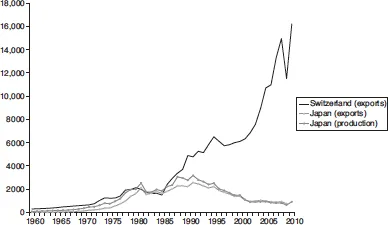

As a result of the extraordinary development of Japanese watchmaking companies in the 1970s, whose production value shot up from USD350 million in 1970 to 2 billion in 1980, Japan managed to overtake Switzerland in 1981–1985 (see Figure 1.1). During this five-year period, the average annual value of Japanese watch production was USD1.96 billion, of which 1.74 billion was for exports, compared with USD1.69 billion for Swiss watch exports (the production value of Swiss companies is not known, but is close to the value of exports, given the small size of the Swiss market, in which sales accounts for some 5 per cent of production). As a result, Japanese competition pushed the watchmaking industry in Switzerland into a crisis situation, marked by a decline and then stagnation in exports as well as a drop in employment. From the end of the 1980s, however, the dynamics were completely different: Swiss exports were booming (USD4.9 billion in 1990, 6.1 billion in 2000, and 16.2 billion in 2010), while Japan’s watch production stagnated, then fell sharply (USD2.8 billion in 1990, 1.5 billion in 2000, and 0.9 billion in 2010).

Japanese researchers working in the management field have focused on the stagnation and decline of the Japanese watchmaking industry. Their work consistently focus on technology as the key factor to understand the dynamics of this industry. Indeed, the Japanese literature of the 1990s and 2000s emphasizes the diversification of products and the transformation of their architecture (the so-called modularization process) as strategies adopted in the hope of regaining lost competitiveness.2 In so doing, they are in total agreement with the actors of the Japanese watchmaking industry, who remain narrowly obsessed by technological innovation. Designing new products and cutting production costs remain the two core strategies which Japanese watchmaking companies have been following, unsuccessfully so far, in their bid to reconquer world markets. On the one hand, they have successively launched genuinely innovative products, such as solar watches (1995), hybrid quartz-mechanism spring-drive watches (1999), and radio-controlled watches (2005), thereby asserting their innovativeness, which remains a key element of their communication strategy. On the other hand, they have relocated a great deal of production outside Japan, mainly to China, in an attempt to reduce manufacturing costs. As a result, the proportion of watches produced abroad by Japanese watchmaking companies has risen sharply, shooting up from 17.8 per cent in 1995 to 24.2 per cent in 2000 and 45.8 per cent in 2010.3 In the final analysis, the aim of this twofold strategy is to bring innovative, inexpensive, and high-quality products to market, in the hope of once again competing with Swiss watchmakers. However, these measures have not helped Japanese watchmaking firms grow or become more competitive.

Figure 1.1 Production and exports of the Swiss and Japanese watchmaking industries, in USD millions, 1960–2010

Note: No figures are available for Swiss production.

Source: Swiss annual foreign trade statistics. Bern: Swiss Federal Customs Administration, 1960–2010; Kikai tokei nenpo. Tokyo: MITI, 1960–2010; Nihon gaikoku boeki tokei. Tokyo: Ministry of Finance, 1960–2010.

Understanding the rebirth of the Swiss watchmaking industry

Whereas Japanese researchers and industrialists attach great importance to technological innovation as a driver of industrial growth and corporate competiveness, Western management researchers and historians explain the extraordinary comeback of Swiss watchmaking on world markets in rather different terms. There are two main approaches. The first, which predominates, may be called the “cultural school” approach. In terms of explanations, it focuses on the industrial district. From this perspective, recourse to a few key elements of the Marshallian district (such as industrial climate and relations of competition–complementarity between companies) makes it possible to interpret the rebirth of the Swiss watchmaking industry as the outcome of a technical culture inscribed in the territory, which has made it possible to reposition the industry at the high end of the market and to manufacture quality products that rely on traditional know-how.4 For example, Hélène Pasquier argues that “watchmaking firms positioned themselves as the guarantors of the age-old regional tradition.”5 This type of reasoning, which is quite widespread and is based on a “romantic description of the district,”6 as the French sociologist Pierre-Paul Zalio puts it, is very close to the narrative produced by the watchmaking industry itself. Moreover, it attaches considerable importance to the Swatch’s role in overcoming the crisis. This innovative product supposedly not only helped the Swiss watchmaking industry prevail against Japan but also enabled it, through the profits earned, to reposition itself to high-quality mechanical watchmaking, through a process which is never clearly exposed in this literature. However, this approach poses a problem, first because it proposes a model which is based on a debatable interpretation of the Marshallian district and an insufficient analysis of the sources, and second because it fails to situate the Swiss watchmaking industry within the global context.

The second approach explains the rebirth of the Swiss watchmaking industry as the consequence of a new marketing strategy aimed at repositioning the sector in relation to its rivals in Japan and Hong Kong. Amy K. Glasmeier showed that the reason the Swiss watchmakers regained their ability to compete was the re-adaptation of the Swiss production system to global competition during the 1980s – what she calls “reorganization à la Japanese,”7 or mass production of a limited number of mechanical calibres (movement without regulating parts), which was the strategy adopted by Hattori & Co. (Seiko) in the 1950s. The work done by Olivier Crevoisier and his team not only highlights the transformation of production systems but also underscores the decisive role played by the new marketing strategies. According to Hugues Jeannerat and Olivier Crevoisier, the success of the Swiss watchmaking industry was even due to precisely “non-technological innovations.”8 Leila Kebir and Olivier Crevoisier clearly showed how the return of mechanical watchmaking in the 1990s was based on the use of such cultural resources as “historical legacy, technique and aesthetics.”9 This process of building a cultural heritage also figures prominently in the work of the ethnologist Hervé Munz.10 Contrary to the cultural school, it is not the existence as such of traditional know-how inscribed in the territory, but rather the use and maintenance of this image for marketing purposes which matters. However, this regional economic research primarily covers the period after 2000 and fails to position this new strategy within the context of a historical process, which could shed light on its origins.

This book adopts the latter approach, but also attaches real importance to an analysis of how the production system is organized. To grasp how Switzerland has been able to return to dominance of world watch markets, one must distance oneself from the high-flown narratives on the age-old know-how and technical excellence of Swiss watchmakers. The circulation of technologies and know-how worldwide is a general phenomenon which has been accelerating since the Industrial Revolution and affects all sectors of the economy.11 Nowadays, high-quality mechanical watches can be manufactured anywhere in the world. Seiko has been making since the 1960’s extremely accurate high-quality mechanical watches and has the know-how to produce tourbillon watches, which are considered the pinnacle of the watchmaking profession (the tourbillion is a small device which eliminates errors of rate in the vertical positions).12 The fact that it has not done so, despite holding the necessary patents, is due to marketing reasons, not technical ones: on the global luxury goods market, watchmaking is Swiss by its very nature. Since the mid-1990s, the transformation of Swiss watchmaking into a luxury industry and its adaptation to the sweeping changes in this sector appear to be the very basis of its success. This far-reaching change is particularly visible when we look at statistics for watch exports.

General trends in Swiss watch exports

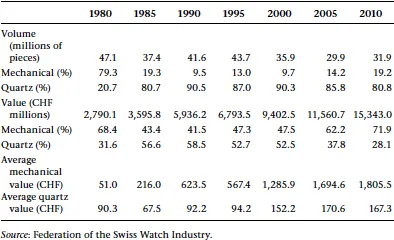

Swiss foreign trade statistics illustrate the overall trend in the Swiss watchmaking industry between 1985 and 2010 (see Table 1.1). There were two distinct phases. First, the years 1985–1995 were the decade when the industry overcame the crisis, as reflected in the overall upturn in exports (in terms of both volume and value) and a sharp rise in the production of quartz watches. The latter accounted on average for 89.2 per cent of the volume of watch exports in the 1990s but barely half of their value. These figures highlight the importance of the restructuring of production systems and efforts to compete with Japanese rivals during this phase.

Second, the years 1995–2010 saw the introduction of a marketing strategy which turned Swiss watches into luxury goods. The volume of exports declined sharply, stabilizing at around 30 million pieces in the second half of the 2000s. On the other hand, the value of exports posted extraordinary growth, reaching CHF15.3 billion in 2010. This boom was based on the strategy of turning mechanical watches into products of prestige, tradition, and luxury: their share of the total export value shot up from 47.3 per cent in 1995 to 71.9 per cent in 2010, whereas their volume showed only a slight rise. In 2010, more than 80 per cent of all Swiss watch exports were quartz watches. Since 1995, however, growth in the watchmaking industry has been driven by the sharp increase in the price of mechanical watches, which are now marketed as luxury goods. Yet, even though marketing strategy appears to have been a decisive factor in this process, production-related aspects must also be taken into consideration.

Table 1.1 Swiss watch and movement exports, 1980–2010

The globalization of the luxury industry

In order to understand the circumstances in which the Swiss watch industry has staged a triumphant comeback on world markets since the late 1980s, as well as the Swatch Group’s strong growth, we must look at the development of the luxury industry as a whole. Watchmaking has been affected by the sweeping changes which have impacted all the industries in this sector since the 1970s, including fashion, wine, and jewellery. The transformation of the luxury industry has been characterized by the rationalization of production, the globalization of brands, and the democratization of use.

Traditionally, luxury products were goods produced in small quantities, often by small family firms, and meant for a small, wealthy elite. However, the creation of multinational companies in the luxury industry, often based on the acquisition and merger of former family firms, has profoundly changed the nature of the products: luxury goods have become objects of mass consumption, bearing hefty price tags but being produced industrially and meant for both the middle and upper classes. Management researchers have developed various concepts to describe the emergence of these new consumer goods. For example, Danielle Allères speaks of “affordable luxury,”13 while Michael J. Silverstein and Neil Fiske use the notion of “New Luxury.”14 The production and sale of such goods has become an extremely profitable activity as a result of the large profit margins generated by an exclusive image maintained by heavy advertising. This can be contrasted with traditional luxury, which is categorized as “exclusive,” involves extremely expensive goods, targets wealthy customers, and usually generates smaller margins.

This transformation has attracted a great deal of attention from management researchers, spinning off a new field of research peculiar to this discipline. Yet these efforts appear insufficient to account for the transformation of Swiss watchmaking in all its complexity. Likewise, modern developments in the European luxury industry remain relatively unexplored by economic historians. The work done in management and the social sciences is generally characterized by a lack of historical perspective and distance in relation to the brands’ version of their own history. A great deal of marketing and management research concentrating on the luxury industry is published by researchers who work as consultants for the large firms in the sector, for which they train the new generations of managers in their universities. This type of research, which is widespread, is aimed more at providing an academic justification for the brands’ narratives than at furthering understanding of their marketing strategies. To cite just one example, Jonas and Bettina Hoffmann wrapped up a study on the watchmaker Richard Mille by writing that “passion is a distinctive characteristic of luxury innovators in their path; it is the source of insights; and it is passion in the execution and the delivery of a rare experience that will make luxury innovation succeed and sustain brand equity in the long run.”15 Marie-Claude Sicard accurately sums up the dominant trend in this field: “Owing to a surprising consensus, no one – neither the media, nor the analysts, nor the authors writing on a given subject – dares challenge conventional ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The Watchmaking Crisis of 19751985

- 3 The Creation of the Swatch Group and the Swatch Legend

- 4 Rationalization and Globalization of the Production System (19851998)

- 5 A New Marketing Strategy (19851995)

- 6 The Major Move into Luxury (Since 1995)

- 7 Omegas Choice

- 8 China: A New El Dorado

- 9 The Swatch Groups Competitors

- 10 Conclusion

- Notes

- References

- Index