eBook - ePub

Conservative Economic Policymaking and the Birth of Thatcherism, 1964-1979

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Conservative Economic Policymaking and the Birth of Thatcherism, 1964-1979

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In this book, Adrian Williamson investigates the processes by which Thatcherism became established in Tory thinking, and questions to what extent the politician herself is responsible for Thatcherism within the Conservative Party.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Conservative Economic Policymaking and the Birth of Thatcherism, 1964-1979 by Adrian Williamson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Histoire & Histoire de la Grande-Bretagne. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

HistoireSubtopic

Histoire de la Grande-Bretagne1

Introduction

In 1976, Margaret Thatcher told a biographer that she had ‘changed everything’.1 This was a bold claim for an Opposition Leader scarcely a year into the role. Upon her death in 2013, even hostile obituarists agreed that ‘the Thatcher years were a watershed ... the ideals of collective effort, full employment and a managed economy ... [were] replaced with the politics of me and mine, deregulation ... privatisation ... Thatcher did not cause these changes, but she legitimised and embedded them.’2 Her biographers echo this, but with admiration. According to Charles Moore, Thatcher fought and won the battle of ideas, imbued with ‘the authority of great thinkers’.3

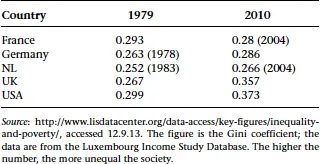

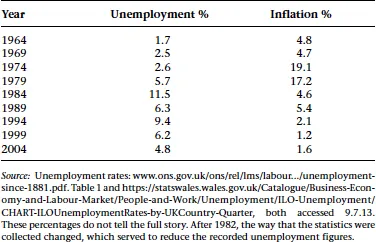

Certainly, there has been profound change. Britain (and Thatcher’s adored USA) became much more unequal, these economies took a very different path from the European social democracies, full employment receded, and attention focused on maintaining low inflation (see Tables 1.1 and 1.2):

Table 1.1 Income inequality, selected countries, 1979–2010

Table 1.2 UK unemployment/inflation rate, 1964–2004 (average for selected years)

Undoubtedly, this change coincided with Thatcher’s political pre-eminence. Such coincidence has led to a conventional account of Britain’s post-war economic history that goes approximately as follows. From 1945 to 1979, most policymakers subscribed to the post-war settlement. This was predicated upon full employment. As a result, the fruits of economic growth were shared quite equally, and governments had to bargain with the trade unions. The oil price shock of 1973/4, and the high inflation of the mid-1970s, persuaded most policymakers that controlling prices was now the top priority. In consequence, the full employment goal disappeared. It was no longer thought necessary, or even desirable, to redistribute wealth or bargain with the unions. What emerged was ‘Thatcherism’, a doctrine culled from the writings of Hayek and Friedman, as interpreted to a waiting world by the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA) and other neo-liberal think tanks.

We will be examining the supposed origins of that change: specifically, policymaking in the Conservative Party from 1964 to 1979.4 Almost everything about this process, and the subsequent direction of policy, is contested. There is fierce debate as to whether the change was necessary, and as to its consequences.5 However, there is little dispute that there was a profound transformation in policy.6 We focus on the process which produced that change: how and why did Conservative policymakers change course? We will be considering primarily the debates taking place amongst leading Tories, their advisers and those seeking to influence them. We are considering the group said to embody the change and at the very moment when, in the conventional account, the transformation occurred. We will consider also, but to a much lesser extent, their Labour opponents. The focus is, however, upon the Conservatives. It was they who were said to have signed up to a consensus over policy, perhaps reluctantly, after the calamity of 1945. It was the Tories also who are commonly supposed to have destroyed this policy consensus after 1979.

There is no agreed definition of the term ‘Thatcherism’, and its use is not to prejudge Thatcher’s own role or the coherence of the project. Indeed, we will suggest that Thatcherism is best understood as a series of programmes, of varying cogency and with markedly differentiated levels of support among supposed Thatcherites. At the core was a package of supply-side or microeconomic reforms. Thus, taxation should be at a consistently lower level, particularly direct taxation and taxation at marginal rates. The nationalised industries were to be privatised wherever possible. The economic, social and political power of the trade unions would be greatly reduced. The economy should be as open as possible to internal and external competition. All Thatcherites, and nearly all Conservatives, believed strongly in this agenda.

Next, there was what Peter Jay described as ‘the New Realism’.7 He was referring specifically to the policies of the Callaghan Government pursued from 1976 to 1979. The conquest of inflation was to be a central aim of macroeconomic policy. Much more emphasis was to be given to monetary rigour. Government was to be disciplined in respect of its finances, with public expenditure held at a stable, or even reducing, proportion of the nation’s output. Once more, all Thatcherites, and nearly all Conservatives, believed strongly in this agenda. However, it was not only Thatcherites who subscribed to the New Realism. Indeed, the identification of such an approach with such a quintessential ‘old Labour’ figure as Callaghan should give one immediate pause as to any suggestion that this shift in policy marked the end of the settlement. After all, while that supposed settlement was in full swing, its high priests were quite capable of practising severe austerity, which bore considerable resemblance to the New Realism.8 Equally, when the 1970s crisis was at its height, the intellectual titans of social democracy such as Crosland and Jenkins told their followers that ‘the party [was] over’, and that the level of public spending was far too high.9 However, they were not then abandoning, and did not later renounce, the settlement. Rather, as Callaghan’s biographer suggests, they were seeking to update the Keynesian programme in the light of new circumstances.10

At this point, however, all that is solid about Thatcherism melts into air. Did Thatcherites believe in greater European integration (the Single European Act) or increased self-determination (Bruges)? Were they ‘monetarists’ and, if so, what did that mean? Did they think sterling should float freely or be fixed within an international monetary system? Did they wish to break the chains of collectivism, or to preserve universal education, health and welfare programmes in challenging times? Was industrial policy to be less interventionist? There is no convincing answer to any of these questions. To a large extent, Thatcher’s governments did one thing, and Thatcherites seemed to believe something quite different. Howe both argued for an essentially passive response to deindustrialisation and urged an enhanced role for the National Economic Development Council (NEDC).11 Joseph embraced the market.12 Yet, when it came to it, he pleaded with his colleagues for increased public support for British Leyland.13 There is throughout inconsistency, uncertainty and contingency: if one is looking for a smooth transition from Keynesianism, one will not find it here.14 As even Moore accepts, there was little in the way of an agreed or coherent Thatcherite programme by 1979.15 The position was no clearer by the time Thatcher fell. In a seminal text, Nigel Lawson proclaimed in 1991 that ‘the conduct of policy is assisted by the maximum adherence to rules and the minimum use of discretion’.16 Yet, ‘that rule [was] best framed in terms of the exchange rate’ and, in particular, membership of the European Monetary System (EMS). Thatcher had bitterly opposed this policy, and it swiftly led to the humiliation of ‘Black Wednesday’.

As we shall see, however, there was a relatively coherent set of answers to the questions posed in the preceding paragraph, and that was the approach advocated by Powell and the IEA. ‘Powellism’, for shorthand, was a form of market-oriented nationalism. Powellites distrusted all international economic organisations but, above all, the EEC.17 Sterling should float freely. Attempts to fix the value of currencies were bound to end in failure. Domestic governments should concentrate on controlling the money supply, the rate of which was the sole determinant of the level of inflation. This was, indeed, the primary economic function of government. It was not for the state to seek to manage demand or intervene in industry or direct the regional allocation of business. Education, health and welfare should be provided by the market, or voluntarily, rather than by governments.

We will, therefore, be arguing that Thatcherism, rather than a single doctrine, is an amalgamation of three potentially inconsistent approaches: Supply Side Reform, the New Realism, and Powellism. This argument is not without its difficulties for, as we shall see, even Thatcher’s closest associates were violently opposed to most of the Powellite prospectus. Moreover, Thatcher was far too canny a politician to venture very far down the road of dismantling the NHS or the social security system. Nonetheless, we suggest that the most helpful way to think of Thatcherism is as an uneasy amalgam of these three creeds, albeit that the Powellite element was strongly contested. Certainly, this seemed to be approximately what Thatcher herself believed by the end of her career, and it is not far away from the line taken by the post-Thatcher Conservative Party. Of course, Thatcherism also involved ‘a dash of populism’.18 How this approach was sold to the electorate, and why the voters wished to buy it, is a fascinating question, but largely outside the scope of the present work.19

Having adopted that model for Thatcherism, we will now seek to set out the essential argument of this book as to how Thatcherism came to be born. The first element, Supply Side Reform, was, we shall see, forged not in the crisis of the 1970s, but in the period after 1964 when the Tories licked their wounds and reformulated policy. The Conservatives were, therefore, already impatient with the post-war settlement by 1965, and eager to depart from the approach to tax, the unions and industry which had prevailed in the 1950s. The glue that held their new agenda together was a desire for more competition. This was symbolised by the overwhelming Conservative commitment to the EEC which, it was thought, would usher in this less ossified economy. The impact of the IEA and like bodies on this process was negligible. In the 1960s, the IEA was a new, marginal body with little influence on Conservative thinking. Its principal political spokesperson, Enoch Powell, was semi-detached from the Conservatives after 1965 and internally exiled from 1968 onwards.

The crisis of the 1970s did, of course, have an effect, but this was not confined to the Conservatives. The New Realism was adopted with enthusiasm across the policy elite. Labour, the Bank of England (‘the Bank’), and the Treasury were likewise convinced of the need to focus on reducing inflation, cutting public spending and adopting a stricter monetary policy. It was only the proponents of the Alternative Economic Strategy (AES) who held out against this consensus. Again, the influence of the IEA and other free market ideologues was minimal. They were but part of an overwhelming clamour. Moreover, and somewhat counter-intuitively, the crisis and its aftermath caused at least some Conservatives to doubt elements of the Supply Side package that they had developed in the 1960s. On Trade Union policy, and the associated issue of Prices and Incomes, they appeared to be moving away from the competitive approach towards a more corporatist solution.

Whilst the Conservative tide was generally running strongly in favour of Supply Side Reform, and, after 1974, the New Realism, the same cannot be said in respect of Powellism. Indeed, in important respects, the Party moved further and further away from, in fact was on a collision course with, Powellism in this period. Thus, there...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Policymaking: Structures, Ideas and Influences

- 3 Tax and Spend: Towards a Smaller State?

- 4 From Prices and Incomes Policy to Sado-Monetarism?

- 5 Conservative Industrial Policy: The End of the Mixed Economy?

- 6 Trade Unions: The Discipline of Law?

- 7 Britains Role in the World Economy

- 8 Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography and Other Sources

- Index