This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book captures Nigeria's crisis management experience and lessons learnt during the five-year tenure of Sanusi Lamido Sanusi as CBN Governor. It provides a backdrop of the sub-prime mortgage crisis in the US characterised by the Lehman Brothers debacle in 2007-08, which precipitated global economic and financial crisis.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Banking Reform in Nigeria by Y. Makanjuola in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Financial Risk Management. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

High Stakes Intervention

In June 2009, the financial grapevine in Nigeria was rife with reports of public sector debt overhang, margin-loans malaise and possible banking sector collapse. As the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) contemplated an official response to the deepening crisis, it was imperative that the CBN’s new helmsman, Sanusi Lamido Sanusi, should have seasoned and trusted advisers to work with him on his impending mission. Habitually, reformers tend to be either traditionalists or progressives, individuals that often challenge and moderate each other’s opinions. For optimum team performance, inherently the most important ingredients are vision and cohesion, the ability to faithfully align behind a robust strategy and to execute conscientiously. In the absence of a standard playbook, the CBN required a novel crisis management approach with the primary goals of delivering the Nigerian banking sector to safe harbour and to ensure that depositors were protected.

In what was probably his first interview to the foreign media in June 2009, the new CBN governor told the Financial Times (FT) of London:

I’ve set myself two primary tasks: the first one is restoring confidence in the financial system. The second one is slightly less conventional but it is actually playing an important role, as an agent for development.

The paper further reported that

Mr. Sanusi plans to lay the system’s failings bare as a prelude to instilling a more robust regulatory regime, by first auditing bad loans and then enforcing stricter disclosure. In one of his first moves, Mr. Sanusi issued a circular restricting banks to lending a maximum of 10 per cent of their loan books to public sector entities; a move he hopes will encourage private sector lending and improve asset quality at a stroke.1

One of the first actions endorsed by the CBN management team was the formation of a special joint committee of the CBN and the Nigeria Deposit Insurance Corporation (NDIC) to conduct a detailed, on-site examination of Nigeria’s 24 banking institutions. With the spectre of a ticking time bomb at the heart of the financial system, the concern was how it could be defused without causing unintended collateral damage.

Hence, with the full backing of the CBN, the joint committee swung into action on a mission to determine the true financial position of the nation’s banks. Without pre-empting the audit outcome, the banks could be categorised into three groups; namely, those that were tangentially exposed to margin loans and oil sector lending, banks that had significant exposure but with enough capital to absorb the losses and, thirdly, banks which had severe liquidity and solvency problems.

The exercise itself was divided into two batches of ten and 14 banks, respectively. The three key parameters under review were: (i) Capital adequacy; (ii) Corporate governance; and (iii) Liquidity.

According to the CBN 2009 Annual Report, ‘the poor asset quality of some banks engendered concerns about the systemic risk arising from their over-reliance on the use of the Expanded Discount Window (EDW).’2 Ordinarily, the EDW allows banks to borrow money on a short-term basis or during emergencies from the CBN, in order to address temporary liquidity problems. A CBN Circular on the Guidelines on EDW Operations3 issued by the Director of Banking Operations in October 2008, stipulated six criteria under which access could be denied, namely if:

(i) The CBN observes an act of undue rate arbitrage in the operations of the institution’s dealings;

(ii) An institution is found to have contravened the provisions of the CBN’s monetary and credit policy guidelines;

(iii) The CBN discovers that the institution is be over-trading or engaged in undue mismatch of its assets and liabilities;

(iv) There is contravention of the clearing houses rules;

(v) There is any contravention or non-observance of provisions of the prudential guidelines; or

(vi) A bank under a holding action fails to comply with the provisions of the holding action.

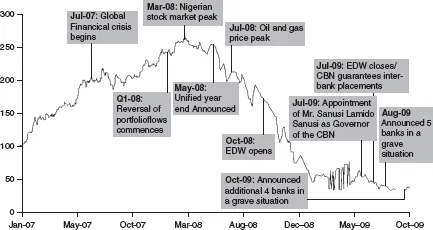

Among the first batch of ten banks, there was obvious evidence that five of them were volatile borrowers at the EDW, which was an indication of overstressed balance sheets. Not only were the contravening banks a source of financial instability but they were also systematically disrupting the interbank market as well. With the EDW facility at N275 billion by May 2009, signifying an obvious red flag, the new CBN governor described the affected banks as being ‘permanently locked in as borrowers and were clearly unable to repay their obligations.’4

More precisely, the 2009 CBN Annual Report provided details of the outcome of the landmark special examination:5

- Five banks failed to meet the statutory minimum Capital Adequacy Ratio (CAR) of 10%, due to capital erosion and additional provisioning for non-performing loans.

- Based on the provisions of the ‘Code of Corporate Governance for Banks in Nigeria’, several of the banks exhibited ‘excessive risk-taking and ineffective risk management, weak internal control mechanisms, undue focus on short-term gains, lack of Board and management capacity, conflicts of interest, and excessive executive compensation’.6

- Investigation into the banks’ exposure to margin loans and proprietary trading activities, the oil and gas sector, and consumer and mortgage credits revealed high levels of non-performing loans (as high as 30%) and severe illiquidity (less than the stipulated minimum of 25%) at five of the ten banks.

The total banking exposure comprising margin lending and the oil and gas sector was approximately N1.6 trillion as at December 2009 (See Figure 1.1). Specifically on the banks’ credit exposure to the latter, crude oil price had earlier peaked in 2008 at US$147 per barrel and well-connected middlemen had taken advantage of market conditions to dominate the retail sale of imported petroleum products. By far, banks’ credit exposure to the oil and gas sector was the highest in the real economy, superseding twenty other economic sectors, including manufacturing, transportation, and real estate.

Undeterred by ridiculously high management fees and upfront interest payments demanded by their banks, these oil marketers ploughed ahead until the global economic shock subverted the speculative and volatile oil market. Shockingly oblivious of foreign exchange and global pricing risks, many banks were taken aback by the sudden downturn that precipitated a drastic fall in crude oil price and the depreciation of the local currency. Left holding devalued petroleum product stocks, credit facilities extended by banks suddenly became doubtful for recovery. By December 2008, banks’ exposure to the oil and gas sector was in the region of N754 billion. This devastating outcome was, of course, further compounded by the precipitous decline in the Nigerian All-Share Index, hitherto anchored on sky-high banking stock valuations.

Figure 1.1 Nigerian banking sector as at October 2009

Source: ‘Project Alpha – Delivery to Safe Harbour’ Presentation (Central Bank of Nigeria).

The 2009 NDIC Annual Report corroborated the findings presented by the CBN but provided these additional details from the perspective of a bank liquidator:7

(i) Inaccurate and opaque financial disclosure;

(ii) Low cash reserves;

(iii) Manipulation of public offer of shares, share-backed collateral lending, and the resultant bubble capital;

(iv) Inadequate provisioning against risky assets (including fraudulent conversion of non-performing loans into short-term securities, such as commercial papers);

(v) Excessive insider dealings and abuse;

(vi) Reckless and fraudulent management; and

(vii) Fraudulent use of subsidiaries (including the use of off-balance sheet special purpose vehicles to hide losses).

The project team set up by the CBN included two directors, two legal advisers and a financial adviser. The CBN governor had deemed it imperative to hire legal advisers before proceeding. The lawyers’ primary role was to ensure that the intervention process was legally unassailable. Once the team had been commissioned, it held its first meeting at a secret location to prevent any leaks. The first conclave was at a boutique hotel in the heart of Ikeja, Lagos, where they deliberated on all possible solutions to the crisis. The plausible options discussed included the liquidation, nationalisation or recapitalisation of financially troubled banks.

Shortly afterwards, the CBN had extended the boundaries of the team dubbed Project Alpha by formally engaging the services of these local and foreign experts: (i) Deutsche Bank, Chapel Hill Denham and Stanbic IBTC as financial advisers; (ii) Olaniwun Ajayi LP and Kola Awodein & Co. as legal advisers; and (iii) KPMG Professional Services and Akintola Williams Deloitte as diagnostic and forensic advisers.

The so-called Project Alpha was predicated on six key pillars, four of which will be analysed in subsequent chapters; that is:

(i) Enhancing the quality of the banks;

(ii) Establishing financial stability;

(iii) Enabling healthy financial sector evolution; and

(iv) Ensuring that the financial sector contributes to the economy.

The last two pillars were complementary and just as crucial:

(v) Ensuring the intervention process was conducted at minimal costs to Nigerian taxpayers; and

(vi) Ensuring the enforceability of all actions carried out under Nigerian law.

Hard choices

So, after receiving the special examination report from the joint CBN/NDIC audit team, what exactly were the CBN’s options? It may be helpful to recall what the CBN governor said in his June 2009 FT interview:

I think it’s also important to send very clear signals to bank executives that it’s not a crime to make a loss, but it’s criminal to lie about it, and people need to understand that.8

Subsequently, the audit report and examiners’ recommendations were approved by the CBN’s Committee of Governors and the top management of NDIC. However, he could not proceed without seeking the approval of the man who appointed him, that is, President Yar’Adua. Also, as the technocratic head of the nation’s apex bank, he would be expected to make and defend his recommendations before the president.

From the president’s perspective, his primary goals would have been the implementation of measures that would restore macroeconomic stability, boost market confidence and foster a healthy banking sector as a catalyst for economic growth and development. However, the problem in Nigeria, and elsewhere, was the threat of a severe recession and stifling credit crunch, a situation whereby financial institutions were unwilling to extend credit to the real economy, and even to each other. Therefore, when banks are unable to play their intermediation role through lending activities, a nation’s economy faces the prospect of grinding to a halt. If, as the CBN governor had suspected all along, the cause of the financial instability could be traced to some troubled banks, the obvious challenge was what the next course of action should be.

Granted that circumstances varied from one country to the next, and also that there were glaring differences between developed and less-developed economies; however, the critical problem they all faced was how to make financial institutions resume lending. As the world’s bellwether economy, it is easy to forget that the public outcry over the US government’s intervention and bailout of major banks overshadowed the fact that more than 200 failed US banking institutions were taken over, merged or allowed to declare bankruptcy between 2009 and 2011.9 In a country built on the principles of individual freedom and free enterprise, there are few public crimes worse than to invoke the ‘N-word’, that is, nationalisation, which to Americans connotes all the purported evils of socialism and commu...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- Acknowledgments

- List of Acronyms

- Introduction

- 1 High Stakes Intervention

- 2 Prelude to the Financial Crisis in 2009

- 3 Fallout of Intervention I – Maintaining Financial Stability

- 4 Fallout of Intervention II – Civil Matters

- 5 Fallout of Intervention III – Criminal Matters

- 6 Ring-fencing Toxic Assets: Establishment of AMCON

- 7 Resolution of Recapitalisation through Bridge Banks

- 8 Case Study: The Union Bank Recapitalisation Process

- 9 Aftermath of Intervention

- 10 Legacies and Lessons Learnt

- 11 Evolution of the Central Bank of Nigeria

- 12 Central Banking in the 21st Century

- 13 Conclusion Epilogue

- Epilogue

- Endnotes

- Index