eBook - ePub

Tracing War in British Enlightenment and Romantic Culture

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Tracing War in British Enlightenment and Romantic Culture

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This volume argues for the enduring and pervasive significance of war in the formation of British Enlightenment and Romantic culture. Showing how war throws into question conventional disciplinary parameters and periodization, essays in the collection consider how war shapes culture through its multiple, divergent, and productive traces.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Tracing War in British Enlightenment and Romantic Culture by Gillian Russell, Neil Ramsey, Gillian Russell,Neil Ramsey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literature General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Shandeism and the Shame of War

‘Buildings fall in different ways. The bombs sheer off the front sometimes, as if with a knife, leaving the rooms inside exposed and furniture still sitting where it had been. Sometimes the bomb leaves nothing but a hole filled with lumps of concrete; and other times structures are concertinaed into asymmetric domes prickly with exposed steel reinforcing rods.’ (Peter Beaumont, report from Gaza, Observer, 20 July 2014)

It is soon clear to anyone reading Tristram Shandy that its wild experiments with writing fiction spring from the impossible challenge of framing a story that lacks the three articles necessary for an intelligible sequence of actions: namely, a coherent space in which they are seen to occur; an orderly lapse of time through which they successively appear; and a recognisable character whom they reveal and prove. Commonly these difficulties are referred to Tristram’s own story of his life, which situates him occasionally in as many as three places at once, and causes him to end his book four years before it begins (which makes it five years before he is born): all signatures of an utterly irregular personality. But his difficulties really begin not with himself but with his uncle. In an attempt to tell Toby’s story Tristram commits himself to the three articles mentioned above. A map of Namur provides the scene, even the actual spot of ground between the St Nicholas Gate and the demi-bastion of St Roche, where in 1694 his uncle was wounded in the groin by a piece of masonry dislodged from a parapet by the impact of a cannonball. The events leading up to this disaster and away from it have a tight calendar kept by the London Gazette, lasting from 1689–1714 and comprising the War of the Grand Alliance and the War of Spanish Succession. The central character in this epochal passage of history is Toby Shandy, praised by Hazlitt as one of the finest compliments ever paid to human nature. So there is a definite space, a historical series, and an admirable character. Why cannot the narrative proceed from the beginning to the end in an orderly sequence?

The answer is that Tristram cannot begin to attempt his uncle’s character without breaching the unities of time and place: if we are to know how Toby acquired his modesty (for Tristram insists this leading characteristic of his relative is not innate) then we have to understand how the harm caused in 1694 by a French barrage against a fortified town in Flanders bears on the hurt inflicted twenty years later by Mrs Wadman’s curiosity about that very same wound. And fully to appreciate the resemblance between these two apparently discrete moments is to apprehend how the whole story, far from being a progress like Hogarth’s or a history like Fielding’s, is really a quilt of simultaneous events, all coloured by military actions and metaphors, each restaging the circumstances of the shock Toby suffered when struck by a fragment of stone. What seemed like Yorkshire is really Flanders; 1714 has turned into 1694; and the character to whom this single event keeps happening is a man who, although prey to deep feelings, is far from certain about his history or identity. No matter how much fun Tristram makes out of this predicament, it is one that is entirely faithful to the radical disorganisation of mind and matter caused by war.

When Edmund Blunden embarks on his own disjointed account of his part in the Somme offensive in 1916, he begins it like this: ‘Let me say here that, whereas to my mind the order of our humble events may be confused, no doubt reference to the battalion records would right it; yet does it matter greatly? or are not pictures and evocations better than horology? What says Tristram? – “It was some time in the summer of that year...”’.1 He takes the phrase from the sixth chapter of the sixth volume of Tristram Shandy, where Tristram begins the story of Lieutenant Le Fever by way of prelude to his non-horological account of uncle Toby’s bowling-green wars. In 1918, in a place near Cambrai called Beugny, Ernst Jünger read some of Tristram Shandy before leading the last of many charges into the setting sun, trying to dispel a feeling of hopelessness. Badly wounded by five bullets, two shell splinters, a shrapnel ball, and four grenade fragments he was somehow extricated from the British advance upon Favreuil, and in the hospital he picked up Tristram Shandy from where he had left off, before sinking into a delirium, ‘one of those fever dreams that are often very amusing’.2 It is no coincidence that these two combatants in the last great European siege war, Blunden and Jünger, should have found Sterne’s novel a faithful mirror of their sense of war’s discontinuities and confusions.

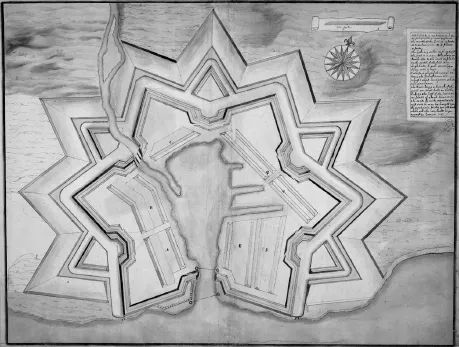

Of all the various forms of battle, siege warfare seems most replete with these impediments to an orderly narrative because it operates according to a fractal logic based on the multiplication of identical phenomena, each a miniature of the total form of the event. With great care and extraordinary fidelity Toby imitates in his garden the pulse of the war of which the siege of Namur formed a part, where labour is commanded not to frame a future benefit for humankind but instead to avert and to attract destruction. Toby raises cities only that they might arrive at ‘a condition to be destroyed,’ and then when they have been levelled, raises them again for the same purpose.3 Like siege architecture itself, whose every improvement is the trace or promise of dilapidation, Toby’s wars are contrivances of ruin. Each vulnerable bastion is reinforced by a ravelin, the ravelin by a half-moon, the half-moon by a tenaille, the one anticipating the ruin of the other. Summing up the history of siege architecture in Flanders, all the way from Namur to the obsolete extravagance of the Maginot Line, W.G. Sebald says the architects of the intricate fortresses of Neuf-Brisach and Saarlouis had forgotten ‘that the largest fortifications will naturally attract the largest enemy forces, and that the more you entrench yourself, the more you must remain on the defensive’.4 The extending crystalline patterns of fortified positions do not trace any evolution of the art of war, or any accumulated knowledge about how conflict can be more decisively joined and sooner ended. These snowflakes of proliferating defensive structures are testimony to the perpetual rhythm of raising up and knocking down that constitutes this kind of struggle, the perpetual alternation of triumph and defeat held forth in arrangements of stone, wood, brass and soil. The half-moon and all its variants stand as memorials to the shattering of the angle it now tries to protect, at the same time as challenging the guns whose success is measured solely by what they shatter (see Illustration 1.1).

What has this to do with the shame of war? I suggest that the anti-narrative stress of the ruin of war is directly proportional to the affective intensities accompanying the experience of it – the elation of victory, the dejection of defeat, and all the passions in between such as gloom, hilarity, fear and boredom. As far as Sterne is concerned these are visible in the manifold shades of the blush, registering severally resentment and remorse, rapture and shame. When Corporal Trim unfolds his plan of a miniature campaign in Toby’s garden, ‘My uncle Toby blushed as red as scarlet as Trim went on;—but it was not a blush of guilt,—of modesty,— or of anger;—it was a blush of joy’ (p. 79). The other sorts of blush have a place elsewhere in the story however. Trim blushes with shame to see the Beguine’s delicate white hand next to his thigh (p. 463), and he blushes with resentment when Bridget reports Mrs Wadman’s suspicions about the extent of his master’s wound. The least hint of Aunt Dinah’s elopement makes the blood fly into Toby’s face, while the intonation of Mrs Wadman’s ‘fiddlestick’ summons all his modest blood into his cheeks (p. 55, p. 369). On the other hand, the blood that makes his heart glow with fire when the compassionate widow leads him ‘all bleeding by the hand out of the trench, wiping her eye, as he was carried to his tent’ is the same that ‘flew out into the camp’ when he was a young man (p. 529, p. 369). Such spontaneous examples of the pressure of blood beneath the skin might seem to be at odds with the alterations of Mrs Wadman’s complexion as she tries rapidly to calculate the social cost of gazing at a man’s naked crotch after Toby promises to put her finger on the very place (‘Mrs Wadman blush’d—look’d towards the door—turn’d pale—blush’d slightly again—recovered her natural colour—blush’d worse than ever’ [p. 514]), but the flushing of her cheeks dramatises the same swift interchange of contrary impulses associated with the map she is shortly to handle. A more immediate mingling of the transverse zigzaggery of fortifications with blushing is evident as Toby watches Walter trying to take off his wig with his right hand while pulling a handkerchief out of his right-hand pocket with his left, causing such a rush of blood to the face that Toby is deterred from sending once again for the map of Namur (p. 127).

Illustration 1.1 Wenceslaus Hollar, Plan of a Fortified Harbour at Tangier, 1627–77, courtesy of the British Museum.

These alternations between the blushes of war and of love feed Sterne’s curiosity about the relation of reddened cheeks to the disarrangement of bodies and structures. The blush aroused by the mention of Aunt Dinah is like the response to a blow. Trim’s blush of resentment, on the other hand, or Walter’s of impatience, are the opposite, tokens of imminent assault. This dialectic is handled awkwardly in Toby’s ‘Apologetical Oration’ where he explains his motives as a soldier purely as the defence of the weak from the aggression of ambitious men, when it is clear that war itself is attractive to him, and that the destruction of things plays a part in the fulfilment of the great ends of his creation. ‘‘Tis one thing, brother Shandy, for a soldier to hazard his own life – to leap first down into the trench... ‘Tis one thing, from public spirit and a thirst of glory, to enter the breach the first man,—to stand in the foremost rank, and march bravely on with drums and trumpets, and colours flying about his ears:—’Tis one thing, I say, brother Shandy, to do this—and ‘tis another thing to reflect on the miseries of war’ (pp. 369–70). The shame of Toby’s war is his failure to understand that these different things are the same thing – the reception of violence and infliction of it – signalled by scarlet uniforms, coloured standards, wounds, and the blush.

In his Two Discourses Concerning the Soul of Brutes (1683) Thomas Willis had tried to show exactly how the blush is answerable to these twin impulses to retire from aggression and to enter into it. Of shame he wrote,

Concerning this Passion, ‘tis observable that when the Corporeall Soul being abashed, is enforced to repress its Compass, she notwithstanding being desirous, as it were to hide this Affection, drives forth outwardly the Blood, and stirs up a redness in the Cheeks.5

He suggests the blush veils weakness, but insofar as it is directed outwards against a likely witness, it belongs to what he calls the power of dilation or emanation, when the soul ‘erects and stretches out itself beyond measure’ in its desire to ‘enlarge the Sphear of [its] Irradiation’.6 The timidity of contraction is a necessary part of the cycle that stimulates the ambition of dilation. Taken on its own as a distinct thing, the blush of modesty or shame is what Mandeville describes when he describes it as follows:

The Heart feels cold and condensed, and the Blood flies from it to the Circumference of the Body; the Face glows, the Neck and part of the Breast partake of the Fire: He is heavy as Lead; the Head is hung down; and the Eyes through a Mist of Confusion are fix’d on the Ground: No Injuries can move him; he is weary of his Being, and heartily desires he could make himself invisible.7

On the other hand, if the dialectic of the blush is examined in its full extent it reproduces the double motion of contraction and expansion Willis has outlined. Here is an outline from The Whore’s Rhetoric:

A seasonable blush is much more prevailing than any artificial supply: it is a token of modesty, and yet an amorous sign... It forces [a Man’s] Blood from the most secret recesses of his Heart, into those amorous parts that soon after pullulate... into a dying transport.8

This at least is the doctrine Mrs Wadman proceeds upon: modest contraction as a prelude to pullulation.

For his part Toby demonstrates at length how pastoral retirement can turn into a military adventure. Landscape architecture derived many of its improvements from military innovat...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on the Contributors

- Introduction: Tracing War in Enlightenment and Romantic Culture

- 1 Shandeism and the Shame of War

- 2 Invalid Elegy and Gothic Pageantry: André, Seward and the Loss of the American War

- 3 Victims of War: Battlefield Casualties and Literary Sensibility

- 4 The Cultural Afterlives of Toussaint Louverture and the Haitian Revolution

- 5 Romantic Militarisation: Sociability, Theatricality and Military Science in the Woolwich Rotunda, 1814–2013

- 6 Exhibiting Discipline: Military Science and the Naval and Military Library and Museum

- 7 Battling Bonaparte after Waterloo: Re-enactment, Representation and ‘The Napoleon Bust Business’

- 8 Turner’s Desert Storm

- 9 Narrative and Atmosphere: War by Other Media in Wilkie, Clausewitz and Turner

- 10 Destroyer and Bearer of Worlds: The Aesthetic Doubleness of War

- Bibliography

- Index