eBook - ePub

Redefining Asia Pacific Higher Education in Contexts of Globalization: Private Markets and the Public Good

Private Markets and the Public Good

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Redefining Asia Pacific Higher Education in Contexts of Globalization: Private Markets and the Public Good

Private Markets and the Public Good

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This edited volume addresses the dynamic global contexts redefining Asia Pacific higher education, including cross-border education, capacity and national birthrate profiles, pressures created within ranking/status systems, and complex shifts in the meanings of the public good that influence public education in an increasingly privatized world.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Redefining Asia Pacific Higher Education in Contexts of Globalization: Private Markets and the Public Good by Deane E. Neubauer, Deane E. Neubauer,Kenneth A. Loparo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Comparative Education. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Comparative Education1

The Perception of Higher Education as a Public Good: The Case of Hong Kong

Siu-yau Lee

Abstract: Higher education has long been seen as a public good that is crucial for the development of a nation-state and the generation of wealth. However, recent years have witnessed growing public concerns in many developed economies over the quality and marketization of higher education. Through an original telephone survey of a representative sample of Hong Kong’s population, this chapter discusses the public perception toward higher education in one of Asia’s global cities. The results suggest that the majority of the population considers higher education as a private good in which the students should be largely responsible for the cost of their education. Further analyses suggest that this perception is more popular among those who have received less education and have a lower income.

Key words: public good; higher education; Hong Kong

Collins, Christopher S. and Deane E. Neubauer. Redefining Asia Pacific Higher Education in Contexts of Globalization: Private Markets and the Public Good. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015. DOI: 10.1057/9781137559203.0006.

Introduction

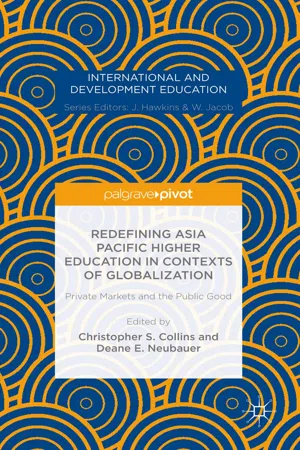

Over the past few decades, higher education in the Asia-Pacific region has experienced rapid transformation, with massification and marketization becoming a major agenda of reform (Mok 2003). Hong Kong is a case in point. Since the 1990s, Hong Kong’s higher education sector has undergone rapid massification. According to official data, in 1980, only 2,579 students (2.2% of the relevant age group) were enrolled as first-year students in local university degree programs. By 2013, however, the figure reached 17,089 (21.3% of the relevant age groups; UGC 2014). Comparatively, although Hong Kong’s gross tertiary enrolment rate still falls well below the average of wealthy OECD countries, the gap closed considerably in the 2000s (Figure 1.1).

FIGURE 1.1 Gross tertiary enrolment rate (%) in Hong Kong, 2003–2012

Note: Gross tertiary enrolment rate is the total enrolment in tertiary education, regardless of age, expressed as a percentage of the total population of the five-year age group following on from secondary school leaving.

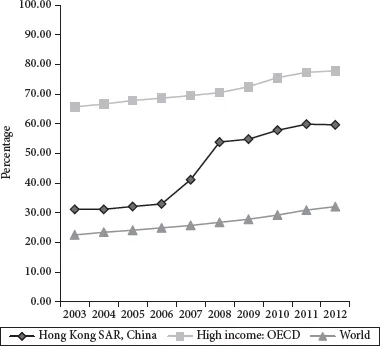

Source: World Bank 2015.

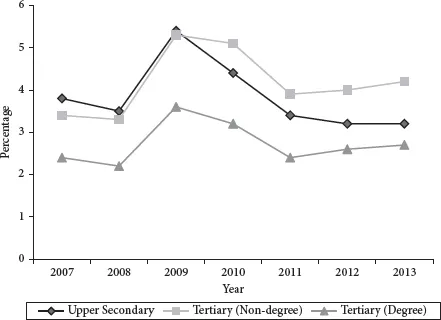

However, as with other countries in the region, the massification of higher education in Hong Kong has been associated with widening inequality in education and decreasing employability. Recent evidence has suggested that attainment of higher education is heavily correlated with family background and that educational inequality has worsened. For example, in 2011, the rate of university degree enrolment of young people in the top 10% of the richest families (48.2%) was 3.7 times that of those in poverty (13%), whereas in 1991 it was just 1.2 times greater (Chou 2013). Also, employment data of graduates from self-financed sub-degree higher education programs—the main area of higher education expansion in Hong Kong—suggest that the premium attached to these programs has diminished rapidly. In 2011, in terms of monthly income from main employment, the difference between graduates of sub-degree programs and upper secondary schools narrowed to around 2,000 Hong Kong dollars (HKD; around 256 US dollars, USD), whereas the gap between graduates of degree programs and upper secondary schools was HKD 15,000 (around USD 1,923; Figure 1.2). Worse still, as Figure 1.3 suggests, since 2009, the unemployment rate among graduates of sub-degree programs has exceeded that of graduates of upper secondary schools. The falling employability and widening educational inequalities cast considerable doubt on the conventional view that higher education is a public good that enhances social mobility and skill-biased industrial transformation.

FIGURE 1.2 Median monthly income from main employment of working population by educational attainment (highest level attended), 2001, 2006, and 2011

Note: The figures include all persons with the educational attainment (highest level attended) of different types of diploma/certificate course, associateship course, or equivalent courses in the 2001 Population Census, and no separate figures were available.

Source: Census and Statistics Department 2015a.

FIGURE 1.3 Unemployment rate by educational attainment, 2007–2013

Note: The unemployment rate is the proportion of unemployed persons in the labor force in the respective groups.

Source: Census and Statistics Department 2015b.

As Neubauer (2008) argues, the creation of new educational institutions and practices often leads to a shift in how higher education is conceived, experienced, and valued. The implications of the massification and marketization of higher education have already been widely discussed in research, and numerous polls have been conducted in the United States and Europe to track how the public views higher education (e.g., Immerwahr and Foleno 2000; Lumina Foundation 2013).1 But so far, in the Asia-Pacific region, where higher education has been undergoing significant transformations, similar work is still in its infancy. Through an original telephone survey of a representative sample of Hong Kong’s population, this chapter examines the extent to which people in Hong Kong agree that higher education should be heavily subsidized by the state. The results are significant not only because they provide new data on public perceptions toward higher education in one of Asia’s global cities, but also because they mark the shifting public–private mix in higher education.

The discussion proceeds in three parts. The first part is a brief discussion on the concept of a public good and its relationship to higher education. The second part outlines the evolution of higher education in Hong Kong. Finally, the third part reports the survey’s findings, which suggest that the majority of the population consider higher education as a private good in which the students should be largely responsible for the cost of their education. Further analyses suggest that this perception is more popular among those who receive less education and have a lower income.

Higher education as a public good

In what sense can higher education be considered a public good? Although the notion of a public good has a long history in Western political thought, its contemporary usage has been shaped by the economist Samuelson (1954, p. 387) who defines public goods as goods which “all enjoy in common in the sense that each individual’s consumption of such a good leads to no subtractions from any other individual’s consumption of that good.” In other words, a good is public if it can be simultaneously consumed by many with very little or no additional cost, and the cost of keeping non-payers from benefiting from it is prohibitive. National defense is a classic example of a public good, not only because it produces a sense of security to all citizens regardless of their contribution to its provision, but also because it is extremely costly, if not impossible, for its provider to charge individuals for the service.

Because public goods are non-rivalrous and non-divisible, private market actors, whose goal is to maximize their individual or organizational interests, cannot efficiently produce them. Given this interpretation, the state should play a leading role in the provision and finance of public goods that are demanded by their subjects (Warr 1983; Roberts 1987; Andreoni 1988). This line of reasoning was particularly popular in the 1960s and 1970s when Keynesian economics was the guiding force of post-war development in industrialized Western countries (Desai 2003). As the role of the state expanded, the usage of the term public good has also been increasingly conflated with state spending or subsidies on goods or services that are not necessarily non-divisible. Public hospitals, for example, are public not because it is impossible for them to identify non-payers, but because the patients they serve pay significantly less than the actual cost of services (Neubauer 2008).

It is against this backdrop that higher education is considered a public good. Universities are divisible, but traditional accounts, as well as many state-sponsored studies, emphasize the importance of higher education in boosting the general economic well-being of the population (Lucas 1988; Acemoglu 1996, 1998; Müller and Shavit 1998; Manski 1992; Moretti 2004; Day and Newburger 2002; Guri-Rosenblit, Sebkova, and Teichler 2007; World Bank 2012; Milburn 2012). They argue that by providing the labor market with more skilled labor, higher education can facilitate skill-biased technical change and increase the overall productivity of the nation, thereby helping the nation to better cope with the challenges of globalization. The view that higher education is a public good not only prompts many governments to reform their higher education sector, but also makes the massification of higher education a highly popular policy goal within the general population. Not surprisingly, therefore, in the past three decades, higher education has witnessed a rapid expansion, especially in the Asia-Pacific region where many countries compete to be a regional education hub.

Ironically, the massification of higher education has led to considerable doubts regarding the public purpose of higher education. Contrary to the conventional wisdom that higher education can promote the general economic well-being of the nation, recent studies suggest that it benefits the wealthy, especially the middle class, more than the poor (Ansell 2008; Johnson 2006). This is primarily because admission to higher education is largely based on academic merit, which is, according to some research, highly biased toward students from the middle and upper classes. As a result, the benefits of higher education are disproportionately captured by the wealthy, especially the middle class, who have the financial resources to support their children to perform well in public exams. The public functions of higher education, as some commentators observe, fade into empty self-marketing claims, leading many to wonder in whose interests higher education is funded by the state (Marginson 2011).

The rapid marketization of growing higher education systems has further complicated the question. While in traditional accounts, state support is treated as one of the defining features of a public good, in the recent decades, many states have restructured their higher education sectors along the lines of decentralization, corporatization, privatization, and commodification (Mok 2007). As universities increasingly rely on tuition fees and support from students and private corporations, knowledge has become a divisible commodity that can be traded in the market to make a profit. Faced with intense competition for students, many universities market their programs as a useful stepping-stone for individuals to achieve career success, rendering themselves an aggregation of private interests rather than institutions that serve wider public interests (Marginson 2011).

The growing ambiguity in the public purpose of higher education highlights an important omission in the traditional accounts, that the identification of public goods is a political process in which the perceptions and interests of key stakeholders can be more important than the actual divisibility and rivalry of the good (Desai 2003). Consider the case of Britain, in which the idea of expanding its higher education system with increased public spending was initiated, contrary to the assumption of many, not by the Labor Party, but by the Conservatives. In fact, when the latter proposed to increase public spending on higher education in the m...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction: Redefining Asia Pacific Higher Education in Dynamic Global Contexts

- 1 The Perception of Higher Education as a Public Good: The Case of Hong Kong

- 2 Higher Education and the Public Good: Creating Inclusive and Diverse National Universities in Indonesia in the Era of Globalization

- 3 Redefining Internationalization: Reverse Student Mobility in South Korea

- 4 Emerging Practices in University- Community Engagement in Malaysia

- 5 Seeking a Redefinition of Higher Education by Exploring the Changing Dynamics of Higher Education Expansion and Corresponding Policies in Taiwan

- 6 International Intersections with Learning Theory: The Role of Feedback in the Learning-Loop

- 7 Changing Dynamics of Asia Pacific Higher Education Globalization, Higher Education Massification, and the Direction of STEM Fields for East Asian Education and Individuals

- 8 Integrating Research into Teaching in the APEX University in Malaysia

- Conclusion

- Index