eBook - ePub

Enterprise Education in Vocational Education

A Comparative Study Between Italy and Australia

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Enterprise Education in Vocational Education

A Comparative Study Between Italy and Australia

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book develops and illustrates a new promising workshop methodology utilized for the first time in a comparative study between Italy and Australia. It is shown how Change Laboratory workshops are useful to trigger sense of initiative and entrepreneurship in vocational students.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Enterprise Education in Vocational Education by Daniele Morselli in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Small Business. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Why Entrepreneurship?

The impact of globalization on our lives

The world is currently living through one of the most extraordinary moments in human history. According to Volkmann et al. (2009, p. 6), “the power equation continues shifting across countries and regions, while rapid changes unfold in the marketplace reshaping both the political landscape and the interactions between governments and businesses”. It has been argued that our societies are becoming more and more open and plural (Cárdenas Gutiérrez & Bernal Guerrero, 2011): within societies, individuals have more opportunities to realize their dreams and their space for action and initiative is improving.

A new definition of human development has come to the fore: “[A]gainst the dominant emphasis on economic growth as an indicator of a nation’s quality of life, Sen [an Indian philosopher and economist who wrote about social justice] has insisted on the importance of the capabilities, what people are actually able to do and to be” (Nussbaum, 2003, p. 33). Human development is seen as a match between the ideas of development and substantial freedom: a “process of expanding the real freedoms that people enjoy” (Sen, 1999, p. 9). In addition to economic assets, human development depends on social assets, such as welfare and education systems, and political ones, such as civil rights and political participation. The freedom to act is represented by the possibilities and opportunities to access diverse courses of action due to individual resources and values. The centrality of the subject with their freedom to act is thus emphasized: thanks to their agency based on their capacities, the individual becomes the trigger for social and economic development, this time inclusive, sustainable and smart (Costa, 2012).

In this context of the expansion of individual freedom, the paradigm of the “entrepreneurial society” is emerging: “[T]he old paradigm of the twentieth century is being replaced with the new paradigm of the entrepreneurial society – a society which rewards creative adaptation, opportunity seeking and the drive to make innovative ideas happen” (Bahri & Haftendorn, 2006, p. IX). The “knowledge era” in which we are living is characterized by the knowledge society and the knowledge economy, and the “knowledge mindset” (Badawi, 2013) becomes important to help the individual “navigate today’s uncertainties and tomorrow’s unknown developments, not only in labour markets but in all aspects of life” (p. 277).

According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), one of the most important changes across societies has been the shift from a “managed” economy to an “entrepreneurial” one (OECD, 2010c). The former was found in mass production societies characterized by “stable employment in large firms and a central role of unions and employers in regulating the economy and society in partnership with government. The social contract included regulation of labour markets and a strong welfare state” (p. 31). This type of society was predominant in the post-Second World War era thanks to the advantages of large companies and large scale production (Audretsch, 2003). However, the importance of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) has been growing since the 1970s in North America and in Europe. The emergence of small niches in the markets, the rapid obsolescence of goods and computer-driven production have made it possible for small companies to compete with the larger ones, taking away most of the competitive advantages big firms used to have. Together with this shift, other changes have occurred: “[T]he growth of the knowledge economy, open innovation, increased global connections, non-technological innovation, the Silicon Valley business model, and social innovation and entrepreneurship – represent an important change in the environment in which innovation takes place” (OECD, 2010c, p. 31). In both advanced and developing economies, the shift to a knowledge society has made knowledge the most important factor of production. In this shift, SMEs have become more competitive due to their ability to be flexible. All these changes have contributed to the emergence of a new economy in which SMEs and entrepreneurship play a crucial role as drivers of innovation growth and creators of jobs (OECD, 2010c).

At the same time, societies are facing global changes extending well beyond the economy, and global competitiveness is making demands on governance, organization and lifestyle structures.

In recent years, the economic fortunes of different countries around the world have become less predictable as national economies become more closely woven together. Companies look for locations with the cheapest operating costs, while capital moves quickly across national borders seeking the highest return. Many population groups find themselves moving to follow employment opportunities or to secure a better quality of life.

(Bahri & Haftendorn, 2006, p. IX)

There is a need to prepare young people for a life of greater uncertainty and complexity, including elements such as frequent occupational changes in job and type of contract; improved mobility; the need to cope with different cultures; the increased probability of self-employment; and more responsibilities, both in family and in social life (Gibb, 2002). Moreover, in the Western economies, phenomena like delocalization have reduced the number of jobs available in manufacturing. At the same time, the level of skills necessary to work in industry is getting wider and deeper:

The world’s population is growing at a time when traditional, stable labour markets are shrinking. In developed and developing countries alike, rapid globalization and technological change have altered both how national economies are organized and what is produced. Countries differ widely in their restructuring practices, but redundancies, unemployment and lack of gainful employment opportunities have been some of the main social costs of recent economic changes around the world.

(Bahri & Haftendorn, 2006, p. 1)

In this scenario, in many countries young people are often left behind.

The issue of youth unemployment

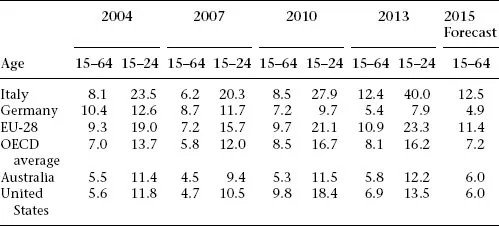

According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), five years after the beginning of the global financial crisis, global growth has started decelerating again and unemployment has risen, leaving 202 million jobless people in 2013 (ILO, 2014). The current trend is expected to continue, and by 2018 there will be 215 million jobseekers. Young people have particularly suffered the consequences of the crisis with 6.4 million dropping out from the job market in 2012 alone (ILO, 2012a). It has been calculated that 74.5 million young people were without a job in 2013 (ILO, 2013). Moving from global figures for unemployment to the OECD countries, the crisis has been particularly severe in some of the most developed countries. In OECD countries in May 2012, for example, 48 million people (equivalent to a rate of 7.9 per cent) were unemployed, 15 million more than in 2007 (OECD, 2012b). Table 1.1 summarizes the figures for joblessness for key OECD countries from 2004 to 2013 with the forecast for 2015.

Table 1.1 General unemployment and youth unemployment rates (per cent) in key OECD countries

Source: OECD Employment and Labour Market Statistics (http://www.oecd.org/statistics/).

The table displays the figures for unemployment for four key countries (Australia, Italy, Germany and the United States), the EU-28 and the OECD average before and during the global crisis. For each year taken into consideration, the left column indicates the overall unemployment figure, while the right column represents the youth unemployment rate. In 2013, while the Australian unemployment rate was two percentage points below the OECD average, whereas the unemployment rate in Italy was four points above it with Italian youth unemployment being 24 points greater than the OECD average for youth unemployment. The overall 2015 forecast for OECD countries predicts that unemployment figures will fall slightly, whilst joblessness will continue to increase for Europe.

In Italy and Australia, which are the focus of this research, the OECD (2012b) suggests that the employment outlook is expected to be quite different. In Italy, which has been hit hard by the crisis, unemployment has been concentrated among youth and low-skilled workers. A comprehensive reform was implemented in 2012 with the aim of combating the segmentation of the labour market, and this is likely to mitigate the social effects of the crisis. On the other hand, it can be said that Australia has weathered the impact of the crisis better, its joblessness rate being one of the lowest of the OCED countries (OECD, 2012b). However, underemployment is still a major problem, especially for women. Furthermore, the labour share has been declining since the 1990s, and the corresponding bargaining power of workers has shrunk.

All in all, youth joblessness is a problem that is common to every nation. In the OECD countries, youth joblessness is at least double the overall rate of unemployment (OECD, 2013). During the years preceding the global downturn, its rate had decreased from 16 per cent in the mid-1990s to 14 per cent in the mid-2000s (Quintini, Martin, & Martin, 2007). In May 2012, youth unemployment rose to more than 16 per cent. A consequence of this is the increasing rate of long-term joblessness: in 2011, 35 per cent of the overall unemployed had spent at least one year seeking a job. This figure rockets to 44 per cent in the European Union (OECD, 2012b). The Southern European countries have the largest percentage of youth at risk (Quintini, 2012). Governments are pushed to take vigorous action against the risk that poor transitions from school to work create in generating social and economic marginality (Quintini, 2011). Not all young people have a satisfying transition from school to work. Those who do not can be divided into two groups. The first group is the “left behind youth” (OECD, 2010b): they lack a certificate or diploma; they come from remote or rural areas; and/or they belong to disadvantaged minorities such as immigrants. As many of them are aged from 15 to 29, they may fall into the category of the so-called “NEET” (neither in employment, nor in education or training). The second group is the “poorly integrated new entrants”. Even if they have some kind of qualification, they end up finding temporary jobs, thus alternating between periods of employment and unemployment even during economic growth.

Overall, the crisis has shown how the problems in the youth labour market are structurally linked to education and training (OECD, 2012a). Tom Karmel, director of the Australian National Centre for Vocational Education Research (NCVER), suggests that nowadays there is “overwhelming agreement on the importance of education and training in the downturn, and this is driven by short-term considerations – the need to keep young people usefully engaged – and long-term considerations – the need to have skilled people in the future” (in Sweet, 2009, p. 3). In developed economies, young people can choose to undertake further education to postpone their entrance into the job market, thus hoping to get a better job when they finish their school path (ILO, 2012b). However, further training and human capital development do not necessarily lead to better or more occupations. As the markets are undergoing rapid changes, the training systems are struggling to catch up, and often students do not have the skills required by industry (ILO, 2012b). Dropout rates are another issue in many countries. In this regard, vocational programmes suffer from higher dropout figures when compared to general education programmes (OECD, 2010a).

Focus on youth unemployment in Europe

According to the European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training (CEDEFOP), although young people have been progressively shrinking in number and becoming more educated, they are experiencing difficult transitions into the job market in many European countries (Cedefop, 2013b): in 2013, 5.6 million youths aged from 15 to 24 were unemployed (Cedefop, 2014). One out of five young unemployed Europeans has never worked, and 75 per cent of these are under 35 years old. As stated by the European Commission (2012c), they need further consideration and help for at least three reasons. First, their situation is more challenging in comparison to that of adults, and it has been deteriorating over time. Young people face high unemployment rates and are increasingly affected by long-term unemployment as well as labour market segmentation. Second, there are negative long-term implications of unemployment at a young age, such as the increased probability of future unemployment, the reduced level of future earnings and the higher probability of working in an unstable job. Third, such negative effects go well beyond work perspectives, encompassing health status, life expectancy and participation in social and civil life. In the Baltic States and in the Mediterranean countries, for example, there is a danger of entering poverty and little probability of exiting from it. Quintini and Manfredi (2009) discuss diverse types of transitions from education to the job market in several OECD countries. In countries like Germany with regulated labour markets and efficient apprenticeships, roughly 80 per cent of the students find a job. In other countries with regulated labour markets but no work-based training within formal education, such transitions prove to be much more complicated. This is the case in Italy and Spain. Employers in these countries tend to hire young people without experience because of their lower labour expenses. This has led to a division of job markets: on the one hand there are well-paid permanent jobs, and on the other hand there are also unstable jobs with poor prospects and protection (OECD, 2010b).

One of the main causes of this is skills mismatch, an issue which can be seen throughout Europe, especially in the Mediterranean countries, with over-education affecting 30 per cent of the youth (Cedefop, 2012b). Recent analysis by the European Central Bank (in European Commission, 2012c) shows how skills mismatches are related to unemployment and are caused by structural imbalances between job demand and supply rather than a lack of geographical mobility. In other words, more highly educated workers do not raise issues of over-qualification as long as industry is able to create a good number of jobs requiring highly educated and innovative workers. It is evident that countries with higher levels of vertical skills mismatches (over- or under-qualification) have some common features (European Commission, 2012b). One is that they have lower levels of public funding in education. This could compromise their capacity to answer to changing requirements of the labour market. Another is that a large share of stakeholders think that the education and training system does not accomplish the needs of the industry. Finally, such countries have rigid job markets, and invest less in job market programmes. In recent decades, the job market in Europe has been reshaped for three main reasons (Cedefop, 2012a). First, technological progress has brought an increased demand for highly skilled workers. Second, delocalization, that is, the production of goods in developing countries, has caused many unskilled jobs to disappear in Europe. Third, the rapid obsolescence of skills is magnified in an aging society. A further influencing factor is the need for new skills required by the advancing green economy. A possible strategy to combat skills mismatch is through higher education in general and specifically through vocational education that provides skills in line with demands made by industry (Cedefop, 2012b).

The European Commission’s youth opportunities initiative (within Europe 2020’s flagship Youth on the Move) has requested the Member States to implement policies so that young people are made a job offer within four months of finishing school. This could be either an apprenticeship or an education opportunity. Europe 2020 – An Agenda for New Skills and Jobs – and the Bruges Communiqué both emphasize the need to invest in young people’s skills so that they are relevant to industry. Moreover, both documents underline the role of vocational education and training (VET). In this respect, many Member States are searching for new policies combining vocational education and labour market services for both the unemployed and new labour market entrants (European Commission, 2011). The principle underlying such policies is that unemployment can be tackled by improving one’s competencies, capabilities and individual motivations, as well as the (re)insertion into active life which is, most of the time, working life (Costa, 2012). Not only do these policies call for a different action from the state, but also from the citizen, who is seen as being aware and participative. Drawing on Sen’s capabilities approach, Costa suggests that the worker’s competent action should be seen in terms of means – that is, agency and substantial freedom – rather than ends such as productivity or level of income. The value of the action stems from the breadth of the possible choices.

Technical and vocational education and training can combat youth unemployment

In this situation, education in general and technical and vocational education and training (TVET1) in particular can play a primary role in effectively preparing young people to live in our fast changing societies. Through its TVET strategy (2012–2015), UNESCO acknowledges the value of vocational education to address youth joblessness, socio-economic inequality and sustainable development (UNESCO-UNEVOC, 2014). According to the Shanghai Consensus:

[C]rises such as the food, fuel and financial crises, as well as natural and technological disasters, are forcing us to re-examine how we conceive of progress and the dominant models of human development. In doing so, we must necessarily re-examine the relevance of currents models of, and approaches to, technical and vocational education in an increasingly complex, interdependent and unpredictable world.

(UNESCO, 2012, p. 1)

Cedefop (2013a, p. 6) suggests that TVET produces a vast array “of monetary and non-monetary benefits, including higher wages, better job prospects, better health and satisfaction with life and leisure for individuals; higher productivity and employee satisfaction for organisations; and higher economic growth and civic engagement for countries”. All in all, “the wide range of benefits generated demonstrate VET’s dual role, in contributing to economic excellence and social inclusion” (p. 6).

Despite its possible role, in many OECD countries VET has been run down in favour of general education and the need to prepare students for university (OECD, 2010a). Furthermore, VET has been commonly considered as low status by both students and the general public. Vocational education has “been associated historically with those classes of society who have to work for a living and who do not partake of the kind of education fit for the gentry” (Winch, 2013, p. 93). As a matter of fact, Winch continues, many state schools have “traditionally had an academic ethos. Transition to employment is not a major preoccupation of their staff, nor indeed is it considered to be a major part of their mission” (p. 107).

However, this could be changing, according to the OECD:

[I]ncreasingly, countries are recognising that good initial vocational education and training has a major contribution to make to economic competitiveness. [ … ] OECD countries need to compete on the quality of goods and services they provide. That requires a well-skilled labour force, with a range of mid-level trade, technical and professional skills alongside those high-level skills associated with university education. More often than not, those skills are delivered through vocational programmes.

(OECD, 2010a, p. 9)

It has been argued that countries such as Germany have done well in tackling youth unemployment as a result of the efficient school to work transitions they provide (Quintini, 2012; Quintini & Manfredi, 2009), and it is widely acknowledged that this is due to their VET and apprenticeship programmes. Iannelli and Raffe (2007) argue that there are two ideal types of transition systems based on the strength of the connections between VET and employment, and served respectively by an “employment log...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables, Figures and Photographs

- Foreword by Umberto Margiotta

- Foreword by Massimiliano Costa

- Introduction

- 1. Why Entrepreneurship?

- 2. Learning Between School and Work

- 3. The Comparative Research

- 4. The Italian Change Laboratories

- 5. The Australian Change Laboratories

- 6. Italy and Australia: A Comparative Perspective

- 7. Conclusions: Vocational Education and Entrepreneurship Education Face Their Common Zone of Proximal Development

- Notes

- References

- Index