This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

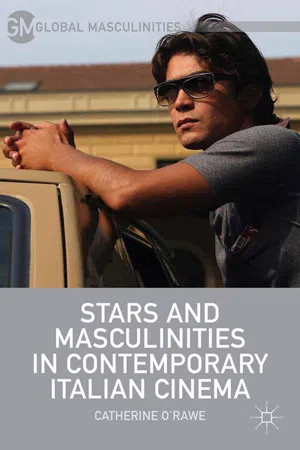

Stars and Masculinities in Contemporary Italian Cinema

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Stars and Masculinities in Contemporary Italian Cinema is the first book to explore contemporary male stars and cinematic constructions of masculinity in Italy. Uniting star analysis with a detailed consideration of the masculinities that are dominating current Italian cinema, the study addresses the supposed crisis of masculinity.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Stars and Masculinities in Contemporary Italian Cinema by C. O'Rawe in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Mezzi di comunicazione e arti performative & Film e video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

P A R T I

Crisis and the Contemporary Italian Man

C H A P T E R 1

Mad About the Boy: Teen Stars and Serious Actors

INTRODUCTION

This chapter takes as its primary focus Riccardo Scamarcio, the actor whose trajectory from unwilling teen heartthrob of films such as Tre metri sopra il cielo (Lucini, 2004) and Ho voglia di te (Prieto, 2007)—both adapted from the cult youth-addressed novels of Federico Moccia—to serious protagonist of middlebrow drama makes him a fascinating figure. The chapter investigates the problems thrown up by the role of the teen idol, looking at the textual strategies that position Scamarcio as a brooding object of the camera’s gaze. The Moccia films have received little critical attention, and the few discussions of Scamarcio that have taken place have focused on his star image and on the heartthrob status the films accorded him. As we will see, the teen film has never enjoyed critical favour, and the target of opprobrium has often been its (presumed) young female fan base. This fan base will be discussed in the chapter, as will the attempts by Scamarcio to move on to more “serious” films, despite critics’ constant references to his status as a (former) teen idol. Scamarcio’s negiotation of his own physical beauty, both via interviews and even by means of self-parody in a film like L’uomo perfetto (Lucini, 2005), will also be addressed. The sexual objectification of the heartthrob additionally highlights the problem of the male pin-up, who of course troubles conventional ideas of the gaze and of hegemonic masculinity. However, I argue that in these teen films there is a complexity of the gaze, both the gaze directed on Scamarcio and that returned by him, which complicates his relationship both with implied spectators and with extradiegetic fans.

The final part of the chapter will look at popular former teen stars Silvio Muccino and Nicolas Vaporidis. Muccino has had a similar career movement to Vaporidis, who, after making the extremely successful Notte prima degli esami (Night Before the Exam) films has moved into producing. Muccino is now writing and directing his own films, and both actors’ experiences testify to the discomfort of the teen idol (a discomfort similar to that experienced by Hollywood idols such as Leonardo DiCaprio and Robert Pattinson), the lack of agency and control associated with the teen idol, and the labor required to effect a successful transition to adulthood and to adult stardom.

The teen film is “often undervalued and disregarded” (Shary 1997: 39) and is difficult to define: Doherty describes it as “elusive” (1988: 12) and “not a critical category” (10). The teen film in Italy is even less studied, mainly because Italian academia has lacked the cultural studies focus of the Anglo-American academy and has tended to work on and celebrate only Italy’s great auteurist or neorealist film heritage. For this reason, it is only recently that some scholarly attention has been paid to Italian teen films: Boero refers to the “adolescent filone [generic strand]” (2009: 9) and “juvenile filone” (13) that grew up in the 1960s, while Capussotti discusses the 1950s as a “fundamental turning point” (2004: 17) in the history of Italian youth, with the creation of a youth culture that would pave the way for the youth-addressed Italian films of the 1960s. However, as we will see in the next chapter, which is devoted to Italian comedy more broadly, the resurgence of popular Italian cinema since the turn of the century can be at least in part attributed to the success of Italian comedies, and Casetti and Salvemini pinpoint the importance to the Italian box-office of “lightweight films aimed at a predominantly youthful public” (2007: 3). They namecheck Notte prima degli esami (Brizzi, 2006) as well as another big hit, Il mio miglior nemico (My Best Enemy; Verdone, 2006) starring Silvio Muccino alongside Carlo Verdone, and Pieraccioni’s Ti amo in tutte le lingue del mondo (I Love You in All the Languages of the World; 2005).1 Spera, meanwhile, pinpoints Fausto Brizzi and Marco Martani, director and writer respectively of Notte prima degli esami, as “the couple who unexpectedly changed Italian cinema” (2010: 39).2 Masoero attributes to Tre metri a fundamental role in the regeneration of Italian cinema in the 2000s, saying that “Tre metri sopra il cielo lays the foundation for the rebirth of the Italian teen film” (2012: 41). Yet these films have been little studied, and even when they are written about a certain tone of patronizing dismissal tends to prevail, a tone that encompasses both the film texts and their audiences; Boero’s allegation that “spectators under twenty don’t have particularly complicated tastes” (2009: 9) is symptomatic of this critical position, which this chapter aims to redress.3

There is no doubt that these teen movies have helped launch new stars such as Scamarcio, Vaporidis, and Muccino, along with many others such as Cristiana Capotondi, Laura Chiatti, and Carolina Crescentini. However, Casetti and Salvemini remind us to bear in mind the role of television in helping to create these stars: “Many of these actors entered the collective imagination through television, which increased their reputation at record speed” (2007: 5).4 The success of Scamarcio, however, is peculiarly tied to books, and to the enormous success of Federico Moccia, author of the novels from which Tre metri and Ho voglia di te (henceforth HVDT) were adapted. It is partly this Moccia connection, and particularly the type of fandom that grew up around Moccia’s textual and extratextual universes to which, I think, can be attributed at least some of the critical disdain to which Scamarcio has been exposed. Moccia has become one of the most successful and influential cultural producers in Italy in the last fifteen years. Tre metri sopra il cielo was initially published in 1994 by a small publisher but its cult popularity among Roman highschoolers meant that photocopies of the book were passed around schools after the small print run had been exhausted. It was reprinted in 2004 by Feltrinelli and sold nearly 2.5 million copies in two years (Galassi 2009: 9). As we will see, it is partly through the paratextual elements of the books and films and the fan practices connected to them that Moccia has become a figure of such suspicion in Italian criticism. Before I address those, though, it is interesting to examine the textual construction of Scamarcio’s character in the two films, and their framing of him.

SCAMARCIO AND THE MOCCIA FILMS: THE HEARTTHROB GAZES BACK

Tre metri is the story of middle-class teenage rebel Step, who meets the equally middle-class but more docile Babi and has a passionate romance with her. After witnessing the death of Step’s best friend Pollo in an illegal motorbike race, Babi breaks off their relationship and retreats to the safety of her parents’ house and a relationship with a respectable boy next door. In one of the only analyses, albeit brief, of Tre metri, Vito Zagarrio claims that the film attracted attention “thanks more to the body of the male protagonist than to that of the female one” (2006a: 235). However, rather than the body of Scamarcio, I would argue that the film showcases his face, and in particular his eyes. The film opens with a forty-second sequence introducing Step: the scene begins with a long shot from above of leather jacket-clad youths dozing at dawn on the steps of a Roman church. Two motorbikes enter the frame, and Step and Pollo dismount and take their helmets off. Step strides over to one of the youths, and when the boy gets to his feet, a close shot from behind the shoulder of the victim shows us Step head-butting his adversary. The camera cuts away as we hear sounds of further blows from Step, who eventually decides to spare the other boy, turns away, and, with Pollo, turns and gets on his bike again. Not a word is spoken. In fact, it is not until several scenes later (and over seven minutes into the film) that Step speaks, when after winning a press-up competition against Siciliano, he replies to the other’s challenge to a possible rematch with a curt “count on it.” Here though, before Step walks away, he turns to gaze at the person whom we presume to be his real antagonist, Siciliano, who later fights him, and the position of the camera makes it appear as if Step is gazing directly into the camera.

Step’s silent gaze is a constant in both films: his first encounter with Babi occurs when he sees her passing in a car and a panning shot in medium close-up reveals him staring at her in silent awe. The relationship between Babi and Step ends in Tre metri with a long shot of him gazing at her as he stands in front of her car in the pouring rain, his face lit up by streetlights; the close-up of his mournful, impassive face lasts for six seconds with the only movement being the blinking of his eyes. It seems that the focus on Step’s gaze has been transferred to an extradiegetic focus on Scamarcio’s eyes, seen as one of his most attractive features. Magazine articles and Internet profiles make frequent reference to his “magnetic eyes” (Niri 2013), “languid gaze,”5 and “blue-eyed gaze”6; the connotations of brooding emotional intensity are clear, as are the films’ attempts to construct Step as a James Dean type. Zagarrio describes Step as “a kind of moody and restless Rusty James” (2006a: 238), referring to the character played by Matt Dillon in Coppola’s Rumble Fish (1983). The iconography of leather jacket, t-shirt, and motorbike is enough to place Step in the tradition of Hollywood rebels, and his brooding inarticulacy apes the “neurosis and sensitivity” of Dean and Marlon Brando; as MacKinnon argues of Dean, “His aggression is explicable at the level of sensitivity which cannot trust itself to be expressed in verbal language” (1997:79). In both films Scamarcio’s acting choices emphasize this nonverbal aspect, and often he will express emotion through the blinking of his famous eyes, or through a nervous swallowing action while his gaze is still fixed on Babi. It is arguable that this underacting (as well as his connection with the despised genre) has led Scamarcio to be overlooked as an actor. Certainly it contributed to his star persona, which after these films was that of “a vulnerable divo” (Canova 2007: 34). Brooding melancholy only increases his star appeal: as Nelmes argues, “In women, melancholy is seen as disabling and negative, whilst in a man . . . it is presented as positive, enabling the transformation of apparent loss into male power” (2003: 270).7

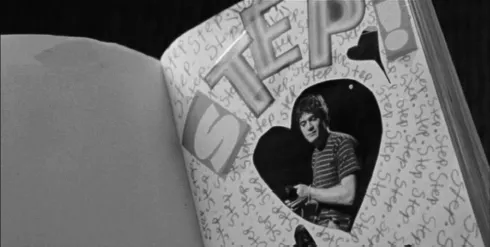

The use of this gaze, which becomes a gaze also toward the camera and the spectator, is picked up interestingly in the opening sequence of HVDT: the film shows Step’s return from America, two years after he had fled there following his break-up with Babi. It opens with a shot of Step’s feet on a moving walkway at Rome airport, accompanied by Iggy Pop’s “The Passenger” on the soundtrack. The shot is held for eight seconds and cuts to a subsequent view of Step with his back to camera, gazing out at the airport grounds. After six seconds he turns round and then deliberately gazes into the camera. The title credits then come up. This star introduction then has built up to the moment of looking at Step/Scamarcio, as one critic notes: “Luis Prieto understood everything well; he intensified and confirmed the link between Scamarcio and his fans by introducing that body a little at a time and making it an erotic object of contemplation” (Gandolfi 2007: 36). Yet what is ignored is that Step is also gazing out at his fans, returning the extradiegetic gaze. This is further complicated by the fact that HVDT takes the gaze at Step/Scamarcio even further than the first one: after the title comes up, the shot changes to a point-of-view shot of someone passing Scamarcio on a different walkway, and then moves to a high-angle view of him ascending an escalator, with the camera again mimicking the viewpoint of a spectator who is passing him on the down escalator. When Step reaches the arrivals area and is embraced by his brother Paolo, we hear the diegetic click of a camera snapping him, though the source is unclear. The sound recurs when they exit the airport and get into Paolo’s car. The paparazzi-style camera clicks have the function of inscribing a sense of Step’s “celebrity” status into the film; this is something that is asserted in other ways, as in the first film Babi’s younger sister Daniela comments excitedly throughout the film on the fact that her sister is going out with a local “star” like Step. We can read this as offering a conventional “fantasy narrative” for girls “in which their favourite celebrity crushes somehow, against all odds, find them, appreciate them, and fall in love with them” (Aubrey et al. 2010: 226).8 However, in HVDT the star status of Step takes a slightly different turn, as at the end of the film it is revealed that the “paparazzo” was none other than Step’s love interest, Gin, who has been stalking him for three years. He finds her journal, in which she has pasted photos she took of him over the last few years, including the ones from the opening airport scene. His celebrity status is made clear from the first page, which has a heart-shaped photo of him with the caption “Step!” and his name written dozens of times (figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 The photo of Step (Riccardo Scamarcio) in Gin’s journal

The captions to the other photos make clear Gin’s status as a Step fan, and by extension, her status as a proxy for Step/Scamarcio fans. They include romantic poems written beside publicity-style photos of Step on his motorbike, references to his “amazing eyes,” and the legend “I will follow you everywhere,” reminding the viewer that the line between stalker and fan is uncomfortably thin. Comically, Gin also takes issue with Babi as Step’s love interest, mirroring some fans’ opposition to that pairing, and Internet disagreements about whether Step-Babi or Step-Gin is the more appropriate couple. Her caption under a photo of Step and Babi together reads “It’s not true. It’s not possible. Not her, NOT HER!”; it seems to reflect an excessive investment in, and an excessive proximity to, Step, and in fact Step’s shock and Gin’s shame at his discovery of her journal seems to put an end to their relationship.9

Yet the film ultimately redeems the abject female fan. Despite the revelation that their relationship was based on a trick (their meet-cute had been orchestrated by Gin based on her knowledge of his movements) and that, according to the photos in her journal, Gin had been secretly present at many of the events in Step’s previous romance, he manages to forgive her with one of his characteristic big romantic gestures. The film’s climax involves him summoning Gin to their previous meeting place, next to the Isola Tiburtina on the river; she stops in amazement as her gaze rests on something the viewer cannot see and then smiles. The scene then cuts to a blown-up close-up of an im...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction Trouble Men: Masculinity, Stardom, and Italian Cinema

- Part I Crisis and the Contemporary Italian Man

- Part II History, Nostalgia, Masculinity

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index