![]()

1

The Persistence of a Local Press: A Folk Memory?

One of the continuing puzzles surrounding the media industry concerns the continuing loyalty which large sections of the general public appear to be displaying towards newspapers, particularly their local newspapers. Despite the fact that the Internet has now been in existence for 25 years and could have been expected to have demolished in large part what had become an arthritic sector, the British local newspaper industry, at least in the UK, while wounded, is still alive.

In the majority of countries in the developed world, the longer a medium has been established, the greater the influence it can command. As newspapers have been around for much longer than any of the newer media, they have the most to tell us regarding the status, history, organisation and longevity of newspapers in Britain, particularly the local press. In the face of the widespread arrival of electronic media (principally but not only the Internet), the traditional news media have survived, depleted but largely intact. Many of their readers have displayed a degree of loyalty which has come as a surprise to many commentators.

Why has this benign influence persisted?

The question which must be asked is as follows: is it possible that the actions of newspaper publishers reporting political and social events in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries would have had such a profound effect upon the general public in the first few years of the twenty-first century? At the beginning of the eighteenth century, the nation was dominated by a combination of the aristocracy and the landed gentry, which controlled Parliament through the control of a very limited and corrupt franchise, directed economic power through the ownership of land in what was a principally rural economy, and provided leadership of both the armed forces and the Anglican Church. This concentration of power ensured that the running of the country remained in the hands of a very small number of people.

It was in this socially stifling environment that the Industrial Revolution began to distribute wealth to, amongst others, the men who were destined to become newspaper publishers. In the beginning, newspapers were subject to efforts to control them through restrictive laws, patronage and rising press taxes; however, these were doomed to fail as Britain became a leading trading nation and the first to industrialise. The increased wealth accumulating to what was now a middle class empowered them, and this was recognised by the 1832 Reform Act, which extended the franchise to the male middle class, but still excluded women and the working class. The existence of this folk memory, which characterised the arrival of local newspapers as a driving force in the eventual enfranchisement of Britain’s working classes, is not beyond the realms of possibility. As the victims of injustice, the British middle and lower classes are bound to have had a deep sense of grievance, giving a long existence to the folk memory.

The middling sort emerge

During what James Curran1 has described as the ‘long eighteenth century’ starting in 1688, marked by the arrival of William of Orange and ending in 1832 when the first Reform Act was passed, the dominance of the aristocracy and the landed gentry began to disappear from the British social and political scenes, to be replaced by the merchants and industrialists who were taking maximum advantage of the opportunities afforded by the industrialisation of Britain. They were what Sir Roy Strong2 referred to as the middling sort, having more standing than the peasantry, but significantly less than members of the Establishment. The critical element was that they had accumulated sufficient resources to invest in the new manufacturing and service industries. It was to be from this emergent middle class that many newspaper founders came.

It was during this time that at least half of the remaining population had no political rights whatsoever; they were generally regarded by the Establishment as the illiterate hoi polloi and were not considered fit to have the vote. However, change was to come from three directions. The first was from the Napoleonic Wars, when the small British army of fewer than 50,000 professional soldiers swelled to almost 300,000, making it the largest organisation of British men ever assembled in a national cause. The discharge of these men from the army when their military service was no longer needed provided a latent threat to the established order, and this was recognised by politicians. The second was the series of Education Acts, which began to permit the education of the masses as much to provide literate manpower for the growing industries, as in the government’s most pressing interests to help prevent the uprising of the masses. The third was the passing of the Great Reform Act in 1832, which Lord Grey, the Prime Minister, spoke of as being designed to ‘prevent the necessity for revolution … reforming to preserve and not to overthrow’. The outcome of the Great Reform Bill was not to institute universal suffrage, but rather to cement the middle classes within the political scene.

Newspaper launches surge

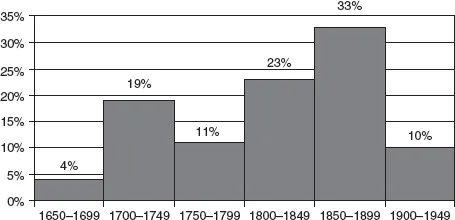

For the general population, it was now clear that change was possible. They could see that the stranglehold of the elite on the politics of the nation had effectively reduced and that universal franchise would be possible in time. Increased literacy had made it possible for everyone who had access to a newspaper to know what was happening in the corridors of power. As an indication of the surge in demand for news, Figure 1.1 below shows the percentage of newspaper titles launched in the country, especially following the wars against Napoleon. While the vast majority of the population were disenfranchised, they could exercise influence either through the middle classes, who had seats in Parliament, or through the various Corresponding Societies, which were calling for universal suffrage.

Figure 1.1 Percentage distribution of newspaper launches (1650–1949)

It was from this time that local newspapers began to occupy a special place in the sentiment of the population. It was through newspaper columns that readers could see what was happening in the political world that they could not yet influence, let alone control. They were, for the first time, being informed, and in a context which differed from that of the national newspapers, in the sense that the latter were suspected of being in the pocket of the old elite, which in many cases they were.

Local newspapers were the net beneficiaries of the feelgood factor which surrounded the progress of democracy in the nation. This resulted in a deep-seated trust of local newspapers developing in local communities, a level of confidence which may have continued to exist up to the present day. In many ways this was gratitude on the part of the general population for the part the local press was playing in the establishment of a sense of entitlement in the working class. Without this loyalty, the local newspaper industry would have largely disappeared as other news media appeared on the scene.

Freed from the restrictions imposed by the landed elite classes and becoming wealthier as the economic effects of the Industrial Revolution spread downwards, a sense of community began to grow, reinforced by the local newspapers operating as a vehicle for the broadcast of the minutiae of local life. The sense of belonging that this fostered added to the perception of self-worth which the increasing demand for wider suffrage was engendering.

Irrespective of the accuracy or otherwise of the folk memory theory, there is no doubt that there is a strong attachment between communities and their local newspaper. It is their voice and their notice board, and it constantly reinforces their identity, something which other forms of media fail to do as effectively.

![]()

2

Communities and Their Media

A member of the general public reading, listening to or viewing an avalanche of seemingly expert opinion could be forgiven for believing that the newspaper industry is on the brink of total collapse and that the rest of the media, with the exception of the Internet, is likely to follow. The evidence would seem to suggest that, while the readership of newspapers has clearly fallen, this smaller audience is likely to display a much higher degree of allegiance to their local newspaper, presumably because, for them, the newspaper is a journal of record of the community, not only archiving the events, threats and opportunities that have occurred, but also providing a voice for discussion and dissent.

In this regard, the local media could be taken to be a significant force for community cohesion by cataloguing the myriad activities taking place within the community. Even within small communities there is a richness of activity that provides a source of news which is of interest within that society, but of little relevance elsewhere. A major motivator for the creation of communities is the individual’s need to belong not only to the community as a whole, but to any local organisation that has an appeal.

Baumann and May in Thinking Sociologically state:

In order for the community and its constituent parts to function efficiently, communication is vital, and this is where the local media have such a critical role to play. While individual organisations, such as churches and clubs, have direct contact with their members, no such facility exists for the community as an entity or for the lower levels of local government. An application for planning permission affects not only the person seeking approval but also a substantial number of neighbours. The extension of licensing hours for a pub may mean the creation of a nuisance through rowdy behaviour late at night. The media bring this level of information to the community, and by doing so strengthen democracy by empowering dissent where needed and support where required.

Viable communities

When communities are large (for example, provincial cities), the viable community units are normally a district of the city based around a neighbourhood shopping centre (the reason for this effect is detailed in Chapter 4). The resulting suburban newspapers carry out the same function as the other local newspapers, but, because of the centralisation of administrative decision-making outside the community, may not have easy access to news relating to local government, where decisions are often made in the overall interests of the city rather than that of any particular community.

Nonetheless, for all local newspapers, the task remains the same: to inform and in some instances to persuade. In the case of national newspapers, the emphasis is rather more on the exercise of persuasion, as their owners almost always support particular political parties and are often purchased for this reason alone. Whereas local newspapers are usually apolitical, even prior to General Elections, national newspapers make no secret of their preferences.

It is perfectly sensible to argue that a symbiotic relationship exists between a community and its media. In the case of a local newspaper, the association is information-centred, while for a national newspaper, it tends to be political. However, for each of these links, the motivating force appears to be the relevant community: the geographical community for local papers and the political community for national papers. Without the requirement on the part of each community to be informed, the newspapers would not exist, and without a continuing requirement, the printed press would be redundant.

Newspapers as a main medium

As the longest established medium, newspapers have experienced most of the opportunities and threats to which media are, or have been, subject. Bearing this in mind, for the purposes of this work, it is felt best to treat the newspaper industry as a foundation of the local media scene, even though its influence has declined and is declining. Throughout most of the history of newspaper publishing, newspapers have been subject to forces exerted from various quarters, either from governments, in the form of Licensing Acts, from the courts, seeking to establish the boundaries of the laws of libel or privacy, or from commercial interests, wishing to obtain for themselves some of the profit and perceived influence that newspaper publishers appeared to have available to them. It did not take long for the newspaper industry to segment into the two main categories of publications that exist today: local and national newspapers.

The point at which the difference became apparent was when transportation, in the form of an extensive railway network, became available, enabling newspapers printed in London and containing up-to-date parliamentary and other reports to become available in most of the large provincial centres at much the same time as the local newspapers were receiving stories from their own London-based reporters or agents. It soon became clear that these proto-nationals had a significant advantage in their access to news sources in and around the centre of power and influence in the capital, an advantage that the provincial newspapers would be hard-pressed to match.

As the sales of national newspapers increased, they gained the significant advantages of the economies of scale that increased circulation brings. Local daily newspapers, lacking the corresponding economies of scale, became more dependent upon the sale of advertising space to enhance their profitability. To support local sales, provincial publishers optimised the local content of their reporting and, as a consequence, the differences between the two types of newspaper became more distinct.

Competition was intense between national newspapers for dominance, first in London, which was (and is) the largest centre of population, and then in the remainder of the country. It was clear from the earliest days that it would be necessary for these newspapers to differentiate themselves by appealing to different readerships, and the easiest of these to reach were the supporters of the various political parties. This is substantially the position today – there are few national newspapers that do not promote the merits of one political party or another, some on a continuing basis and others from time to time.

Local media in Britain are largely apolitical

Whereas national newspapers compete nationwide, provincial newspapers are restricted to the geographical extent of the community they seek to serve. This means that there ...