eBook - ePub

Life After Debt

The Origins and Resolutions of Debt Crisis

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Life After Debt

The Origins and Resolutions of Debt Crisis

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This volume provides a pluralistic discussion from world-renowned scholars on the international aspects of the debt crisis and prospects for resolution. It provides a comprehensive evaluation of how the debt crisis has impacted Western Europe, the emerging markets and Latin America, and puts forward different suggestions for recovery.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Life After Debt by J. Stiglitz, D. Heymann, J. Stiglitz,D. Heymann in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Macroeconomics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Analytical Issues

1.1

Crises: Principles and Policies

With an Application to the Euro Zone Crisis1

Joseph E. Stiglitz

Economies around the world have faced repeated crises – more frequently over the past thirty years.2 The fact that they have become more frequent and pervasive at the same time that we believe we have learned more about the management of the economy and as markets have seemingly improved poses a puzzle: shouldn’t rational markets avoid these catastrophes, the costs of which outweigh, by an enormous amount, any benefit that might have accrued to the economy from the actions prior to the crisis that might have contributed to it? This is especially true of the large fraction of crises that can be called “debt crises,” precipitated by a country’s difficulty in repaying what it owes. The benefits of income smoothing (arising from the difference in the marginal utility of income in periods when income is low and when income is high) are overwhelmed by the social and economic costs of the ensuing crisis.

For economic theory, crises pose another puzzle: typically the state variables that describe an economy change slowly. But what distinguishes a crisis is that the state of the economy seems to change dramatically, in a relatively short time. This should be even more puzzling to those who believe in some version of rational expectations, for shouldn’t markets have anticipated the untoward change of events? And if they had done so, wouldn’t the problems have appeared earlier? There is seldom any single item of “news” that leads to the kind of radical revision of expectations that often seem to be associated with crises.3

For those who believe in well-functioning markets, there is yet another puzzle. The assets – the human, physical, and natural capital – of a country are essentially the same after the crisis as they were before. A misallocation of capital before the crisis – say as a result of a housing bubble – should imply that incomes after the crisis would be lower than would otherwise be the case. But there is nothing in standard theory to suggest that there should be a high level of unemployment, or a dramatically lower level of output. Indeed, properly measured, GDP might even increase. This is true even if there is a legacy of debt. Debt should affect the claims on society’s resources, that is, how the national pie is divided; but that’s all.4

Keynesian economics provides some insights into these puzzles – certainly more than neoclassical models that assume that the economy is always at full employment. But standard Keynesian economics had little to say about dynamics: it was an equilibrium theory, attempting to explain the persistence of unemployment. It made no attempt to explain why the breaking of a bubble should have such adverse effects. Although modern variants of New Keynesian economics (originating with the work of Fisher5 that was contemporaneous with Keynes, and updated in the work of Greenwald and Stiglitz [1988a, 1988b, 1990, 1993a, 1993b) help explain why shocks to the economy that have significant effects on balance sheets would have persistent and long-lasting effects,6 they don’t really explain crises – why there should be events with large balance sheet effects – at least within a theory disciplined by some variant of rational expectations. (Of course, if we are willing simply to posit large changes in expectations and/or a change in asset prices unrelated to any change in underlying fundamentals, then it is easy to generate crises, especially of a kind associated with large changes in balance sheets.)

The euro crisis, and the Great Recession which led to it, provide dramatic instances of these puzzles. And a study of the unfolding euro crisis provides hints as to the plausibility of alternative explanations, and the strengths and deficiencies of different theories.

After providing a general theory of crises, in which multiple equilibrium and discontinuities in expectations play a critical role, we will then focus on the role of adjustments and the reasons that requisite adjustments sometimes don’t occur.

1.1.1 A theoretical taxonomy of crises

Not all economic downturns are crises, but economic crises almost always become severe downturns, of varying durations. Broadly speaking, we can identify three categories of economic fluctuations:

(a)Short-term fluctuations, brought on by, for instance, excess inventory accumulations or central banks stepping on the brakes too hard in an overzealous fight against inflation. (Occasionally, short-term fluctuations can be brought on by a supply shock, such as a drought.)

(b)Somewhat deeper and longer-lasting downturns, the balance sheet recessions described earlier, often associated with the breaking of a bubble or the sudden realization that an important price (or set of prices) in the economy (such as the exchange rate) has been set “incorrectly,” with consequences of a persistent (and evidently unsustainable) departure from “equilibrium.” Prior to the 2008 crisis, many economists had, for instance, argued that out-of-equilibrium exchange rates (sustained in part by government interventions) had led to global imbalances, and that a disorderly unwinding of these global imbalances would result in a crisis.7 As it turned out, it was the bursting of the housing bubble in the United States, rather than the global unwinding of global imbalances, that led to the crisis.8 Those crises associated with credit excesses (leading to bubbles) have become dubbed Minsky cycles. But while Minsky (see, for example, 1982) and Kindleberger (1978) have identified repeated patterns of credit excesses – often fueled by collateral-based lending, where, as real estate prices increases, the value of collateral on which lending is based also increases – it is hard to reconcile such excesses with rational expectations.9

(c)Deep structural crises, such as the Great Depression, which seem to last far longer than can be accounted for by the slow process of repairing balance sheets. These arise out of the difficulties that market economies have in making large structural changes, which typically require significant investments in restoring the strength of those whose human and other capital has been eviscerated by the economic change; because of imperfections in capital markets (explicable in terms of information asymmetries) those who need to make these investments are constrained from doing so, and thus labor, which needs to be reallocated to reflect the structural change, is impeded from doing so. The breakdown of financial institutions in the midst of these long-term downturns only serves to prolong them.

Identifying the nature of the crisis (or downturn) is not always easy, partially because a crisis of one type may morph into one of another type, partly because any long-lived crisis will have real balance sheet effects and will be associated with problems in the financial sector – even when the financial sector was not the original cause of the crisis.10 There are strong reasons to believe that the downturn that began in 2008, the Great and Long Recession, is structural in nature. The fact that output fell in many countries in which there was no financial crisis (for instance, in manufacturing economies such as China) shows that it affected more than just the finance sector. The continuing weakness in the economy in the US, in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis, where bank and corporate balance sheets have been largely restored (at least to the point that investment outside of real estate has returned to near-normal levels11) suggests too that it is more than a balance sheet recession.12,13

This paper focuses on the latter two – and especially the third – kind of downturns, which are often deep and long lasting.

1.1.1.1 A general theoretical framework

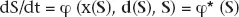

A crisis is a sudden change in the (perceived) state of the economy, one which is often associated with the collapse of a currency, the banking system, or the real economy. It is a sudden change in the performance of the economy. Standard models of the economy model the flow variables (consumption, investment, etc.) x as a function of a set of variables that describe the state of the economy, S, and a set of decision variables, d, which themselves are typically a function of an expanded set of state variables, which include expectations of the future. For simplicity, we write d = d(S), so that the flow variables can be expressed simply as a function of the state of the economy. The state variables change according to a law of motion,

Because S changes slows, x and d change slowly. There should be no crises.

Occasionally, there are what may be viewed as exogenous changes that can lead to a sudden large change in the relevant variables. The above formulation should be generalized to include uncertainty; there can be an “outlier” realization of a random variable (a drought), and, particularly in the presence of non-linearities, this can have a large impact on the state and behavior of the economy.

But most crises are not related to the realization of a 3-standard deviation shock in an exogenous random variable. The 2008 crisis was related to the real estate crash, the 2001 recession to the bursting of the tech bubble. Both were endogenous disturbances. There were no large exogenous events that could have accounted for these crises.

Looking over past crises, there are four possible models that can describe the observed dynamics.

A.Multiple momentary equilibrium. Many economic models are characterized by multiple momentary equilibria. That is, a given set of state variables maps not into a single set of flow variables, but into a multiplicity of possible equilibria. We may not (and typically do not) have a complete theory of determination of equilibrium: how one or the other members of the set happens to occur. For instance, if the “market” believes that a firm (an economy) is not likely to go bankrupt, interest rates will be low, and at the low interest rate, the probability of bankruptcy will be low. But if the market believes that the probability of bankruptcy is high, then there will be a high interest rate, and a correspondingly high probability of bankruptcy. Both of these can be rational expectations equilibria (see Greenwald and Stiglitz, 2003).14 The defining characteristic of such models is “positive feedbacks.” With multiple momentary equilibria, the economy can move suddenly from one configuration into another – with the latter, for instance, having disastrous consequences for the economy or some group within the economy. To take up the example just given: if, suddenly, the market believes that there is a high probability of bankruptcy and interest rates (rationally) adjust to reflect this, then not only will the behavior of the economy change suddenly, but so will its evolution. In short, there can be discontinuous changes in x even if S (now understood to include only the “real” physical variables, like capital stock) changes slowly, and these discontinuous changes in x can lead to discontinuities in the pattern of changes in S. (S may still be a continuous variable, but S(t) is not differentiable).

B.Expectations as State Variables. While physical objects (like the capital stock) typically change continuously, this need not be the case for beliefs. And this includes beliefs about the future value of state variables. Since dS/dt is not continuous when the economy changes from one momentary equilibrium to another, it is clearly conceivable that individuals (even rationally) could suddenly change their beliefs about the future course of the economy. For instance, if there are multiple momentary equilibria corresponding to every S(t), then as the economy “chooses” one or the other, the future course of the economy changes dramatically. This uncertainty can be rationally incorporated into beliefs ex ante.15 Changes in the future course of the economy get reflected, of course, in the values of assets, so that though the physical assets themselves change in a way which is continuous, the valuations themselves may change in ways which are discontinuous, leading to – and reinforcing – discontinuities in behavior.

The fact that in these and related models of dynamics expectations can play such a central role is consistent with the financial sector’s emphasis on the role of confidence. If the market has confidence (for example, that there is only a low probability of default), then interest rates will be low, as we have noted, and the probability of a default will be low. But such assertions do little to help explain (or affect) expectations, though sometimes they can be thought of as helping to construct sunspot equilibria,16 where certain government actions (like raising interest rates) serve as a coordinating mechanism on expectations (for example, that inflation will be low).

C.Multiple long-run equilibrium. Even if there is a unique momentary equilibrium, there can be multiple steady states, and the steady state to which the economy converges can (and will typically) depend on the initial conditions, So. Slight changes in these can lead to the convergence to a different equilibrium. Again, while S is continuous, dS/dt is not, and there can be sudden changes in the prospects of the economy as a result of a shock that moves the economy across a boundary. Debt can, for instance, go from being “sustainable” to being “unsustainable.”

Behaviors are likely t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- Part I Analytical Issues

- Part II Debt Crises: Varieties of Experiences

- Part III Debt Defaults: Costs and Restructuring Games

- Part IV Dealing with Crises: Instruments and Policies

- Index