Hans Haacke is a German-American artist born in 1936 in Köln, Germany, and since 1965 living in New York. His practice is related to conceptual art, with a long list of works, exhibitions, commissions, international honours and publications to his credit. In 1970 Haacke was invited by the Guggenheim Museum in New York to stage a one-person show, which was “for a German-born artist just thirty-five years old …. a remarkably early canonisation.” 1 Shortly before the exhibition was due to open in April 1971, the Museum Director, Thomas Messer, cancelled it on the grounds that three of the works produced for the exhibition were not art but journalism.

The rejected works were

Shapolsky et al. Manhattan Real Estate Holdings,

a Real-Time Social System,

as of May 1,

1971 and

Sol Goldman and Alex diLorenzo Manhattan Real Estate Holdings,

a Real-Time Social System,

as of May 1,

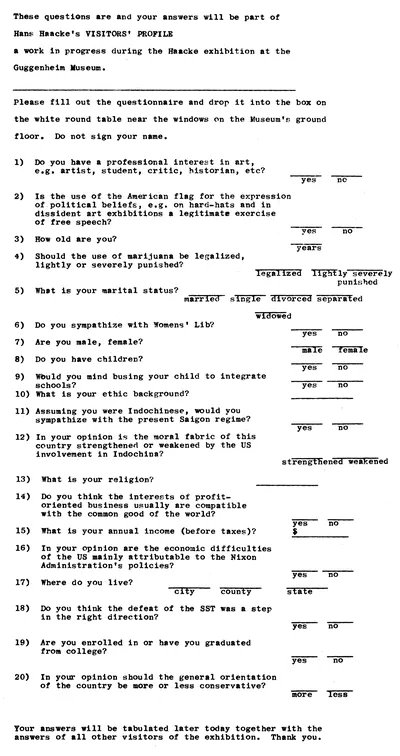

1971, plus a proposed anonymous survey for exhibition visitors. The survey comprised twenty questions about demographic status and political, social, and economic attitudes (Fig.

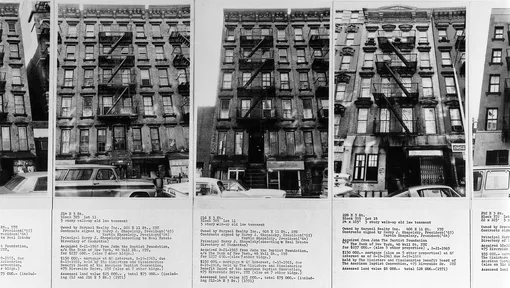

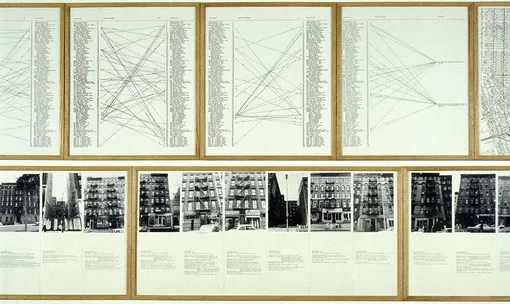

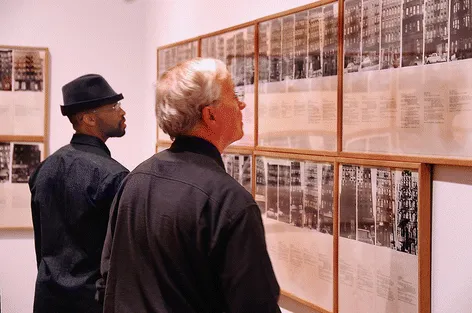

1.1). The two real estate works comprised a series of black and white frontal photographs of slum tenement buildings in a flat uninterpretive style, supplemented with publicly available information from the New York City County Clerk’s Office detailing lot number, address, basic building description, ownership and most recent transfer, assessed land value, and mortgage status (Fig.

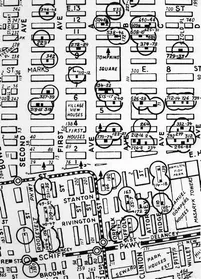

1.2). A street map identified the location of the properties (Fig.

1.3), and charts detailed the various companies and individuals that owned the properties, the interconnections between them, and the sources of mortgage funding (Fig.

1.4). Shapolsky, Goldman and DiLorenzo did not have any association with the Guggenheim Museum.

The curator of the exhibition, Edward F. Fry, was a well-published authority on cubism and contemporary art. He wrote: “In his works Haacke has succeeded in changing the relationship between art and reality, and consequently he has also changed our view of the evolution of modern art.”

2 Fry defended Haacke’s work and was in turn sacked by Messer, never again to be employed by a US museum despite his preeminent international reputation, although he did go on to have a successful academic career in the USA.

3 Quite clearly, the scale and scope of this confrontation indicated that much more was at stake than a mere difference of opinion over the merit of some individual artworks.

Shapolsky was exhibited in a group show the following year at the University of Rochester and at the 1978 Venice Biennale; it and

Sol Goldman were subsequently purchased by the Centre Pompidou in Paris and the Tate Gallery in London, respectively.

4 Haacke had a solo show at The New Museum of Contemporary Art in New York in 1986, and other work by him has been exhibited in the USA over the years at commercial galleries, in group shows and at some smaller public institutions, but until 2008 not in a solo exhibition at a leading US public institution.

Shapolsky was co-purchased with the Museu d’Art Contemporani Barcelona (MACBA) in 2007 by the Whitney Museum of American Art, where it was included in a group show of recent purchases the following year (Fig.

1.5).

In the meantime Haacke had been enormously productive and exhibited in leading venues internationally, including multiple invited appearances at Documenta and the Venice Biennale. He was invited by the newly reunited Germany to occupy that country’s pavilion at the 1993 Venice Biennale, where he and fellow exhibitor German-Korean artist Nam June Paik were awarded the Golden Lion Prize for the best pavilion of that year. In 2000 he was commissioned amid controversy by the German Bundestag to produce the work

DER BEVÖLKERUNG for the renovated and reoccupied Reichstag building in Berlin. In 2012 he was invited to produce a new work and stage a major retrospective by the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia in Madrid. This exhibition was titled

Castles in the Air, and concerned the contemporary burst real estate bubble and impact of the global financial crisis in Spain; the retrospective included the

Sol Goldman piece excluded from the Guggenheim forty-one years earlier. In 2015

Gift Horse was commissioned by the City of London to occupy the vacant fourth plinth in Trafalgar Square (Fig.

1.6). So the jury of his peers, major galleries, and leading scholars and critics internationally,

contra Thomas Messer, has judged that Haacke’s work is certainly art, and indeed that he is one of the major artists of the last half-century.

But we cannot let Messer go so lightly, and have to ask – is it also journalism? And if so, what is journalism? This book addresses these two questions. Its short answer to the first is yes, to that extent agreeing with Messer, but that opens up the much more interesting questions of what sort of art is journalism, and inversely what sort of journalism is art, and what do the two have to offer each other? I will come back to these questions in Chap. 7. A long answer to the second question – what is journalism? – is the main project of this book.

The conflict over Shapolsky and Goldman reflected a major rupture in the way that art was to be conceived and practiced, a rupture that precipitated a new way of thinking about art in relation to reality. If the art is also journalism, then similar issues arise: what is the relationship of journalism to reality? This is a profound epistemological issue, which in journalism studies is still largely stuck in the rut of debates about representation. Fry’s claim that Haacke’s work transcended the representation debates in art signals a comparable opportunity for journalism, and forces an engagement with the basic epistemological and ontological issues that confront any truth-seeking practice. This book is a response to that opportunity.

With few exceptions since 1971, Haacke’s supporters among scholars, critics, and fellow artists and curators have not responded to the journalism side of the challenge. They have explored, analysed, and praised the implications of his work for art, while his detractors have damned it for the same, but for both, journalism has been a known object from which art can and should be distinguished. In this view, art is open, dynamic, fractious, and intellectually contestable, whereas journalism might as well be a urinal or paint rag as far as its intrinsic interest is concerned. But for those who take journalism seriously, Haacke’s work provides a provocation and an opportunity for a breakthrough in how we might think about journalism, both as art and as a rigorous, reflexive truth-seeking practice.

On the art side of the equation, as Fry observed, by 1971 Haacke’s work had been raising fundamental questions about the relationship of art to reality for some time, and the rejected works were just an extension of this challenge into the social realm:

As young Roy Lichtenstein put the case in a famous interview, the problem for a hopeful scene-making artist in the early sixties was how best to be disagreeable. What he needed was to find a body of subject matter sufficiently odious to offend even lovers of art. And as everyone knows, Lichtenstein opted for the vulgarity of comic book images. Here’s what he said to Gene Svenson in November 1963:

It was hard to get a painting that was despicable enough so that no one would hang it – everybody was hanging everything. It was almost acce...