This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

As national leaders struggle to revive their economies, the people of Europe face a stark reality, which has created an opportunity for local leaders and citizen movers and shakers to rise to the occasion to spur revitalization from the bottom up. The author offers a six-point plan to prosperity.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Creating Economic Growth by M. Magnani in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Economic Policy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Building Assets of Local Development

The role of human capital, civic capital, and local governance

If you buy an early-season tomato in Europe, chances are you might be purchasing one grown in the province of Ragusa, Sicily. That’s not only because Sicily has the agricultural advantage of roughly seven hours of sun a day and not much cold. It’s because the region has made an effort to become a leader in growing greenhouse produce. Along the southeastern coast of the island, ‘hothouses’ line up for miles. They are as common as tourists in the summer sun.

To passersby, the army of greenhouses on the Ragusa coast may appear low tech. Many are wooden-frame affairs, covered with sheets of polyethylene. But the homegrown look is deceptive. The region has invested in a host of efforts to leverage native agricultural strengths to make it a global competitor. One of the local initiatives is supporting research on effective greenhouse technology.

A part of that is university research. In 2012, the nearby University of Catania sponsored its third agricultural conference in Ragusa, this one on worker safety in greenhouses.1 One paper looked at the risks of heat to workers. The conference represented one of many efforts to make Ragusa a force in agriculture. In this case, a partnership between the academia and the community leads the way.

An interesting indicator of Ragusa’s economic advance is the rapid increase in employment for women. Four times as many women as men count themselves as shareholders in social cooperatives in Ragusa. Women are especially talented in working and managing firms in the food-processing and service sectors. Even after the recession of the past few years, the rate of participation in the workforce in Ragusa in 2013 was 40.7 percent, still low compared to the rest of the country and to Europe but high for Sicily and the south of Italy.

Ragusa’s support for such advances in agriculture and employment illustrates the first of our six recommendations for revitalizing local and regional economies: building human capital, civic capital, and institutions as the means to get the most out of native strengths. Through such actions, Ragusa has lifted itself to an enviable spot in Sicily. Since 1999, exports from Ragusa have grown more than 50 percent. Unemployment, at about 9 percent in 2011, has stayed well below that of Sicily and southern Italy. Female unemployment has fallen to 10 percent, compared to the Sicilian figure of 15.8 percent, and in line with the national rate of 9.7 percent.

Tomatoes are not the only reason for the relative economic vitality, but they serve as a symbol of revitalization. So does the boomlet in tourists to the Ragusa coast – known for its endless sand beaches. And so does the celebrated handmade Ragusano cheese, for which Ragusa claimed a PDO mark (Protected Designation of Origin, a form of protected geographic status) in 1995. Ragusano is a hard cheese much loved for its sweet flavor when young and spicier flavor when aged. It comes from Modicana cows grazing on grasses and wildflowers on the Sicilian uplands. Modica, a town in the province of Ragusa, is also renowned for its chocolate, still made using the technique of the ancient Aztecs of Mexico.2

To be sure, Ragusa has not performed an economic miracle. It has further to go in building the robust economy of the most vibrant locations in Europe. But it shows that local and regional leaders can take the initiative where leaders at the national level do not. Local leaders can inject dynamism into their economies by nurturing often-neglected local and regional assets – and in so doing grab a share of global commerce in produce, fruits and vegetables, dairy, chocolate, and tourism. And they can do this even in a region not known for economic vitality – and in a country with policy paralysis at the national level.

In other words, not just any community with greenhouses and a lot of sun can succeed in the global produce trade. It takes local and regional leadership to conceive, cultivate, fund, and manage the factors upon which that export machine depends. That is the case in Ragusa.

The significance of Ragusa could easily be written off as having few implications for the rest of Europe. But that would be a mistake. Today, every locale, no matter the country, faces an intensifying challenge: How to create increasing value when people elsewhere in the world can easily copy your products and processes. The solution, as Ragusa shows, is to turn challenge into opportunity: Don’t try to fight the commodity products of copycats. Create newfound value from superior, hard-to-copy, and often tacit knowhow.

In a world where many developed nations cannot compete on price, local savoir faire can become a global competitive advantage. Prosperity depends on the ideas of people and the complexity of products and processes managed by these people. Talented, motivated, clever individuals – working together in a variety of ways that we discuss in this and the next five chapters – are the basis for the generation, production, and commercialization of hard-to-replicate products and services that can restore economic vitality.

The way forward

Even in developed nations, however, support for local economic growth based on such a philosophy is often lacking. That puts the spotlight on leaders and community members who can stand outside that norm. Local people have the opportunity to take action to build local economies on their own. They have not always taken that opportunity in recent decades, and that leads us to a point we make again and again in this book: Local and regional leaders, including ad hoc citizens and business leaders, do not have to wait for leaders at the national level to pull them up. They can do much more to pull themselves up by their own bootstraps.

Relying on national leaders to take action is a loser’s game. Invariably, given today’s pressures, these central leaders will not (or cannot) deliver on expectations. People at the local and regional level will become frustrated as a result. Worse, locally elected leaders will use the inaction at the national level as an excuse for their own lack of performance. This can trigger a mentality of victimization, with both citizens and leaders obsessed with articulating complaints rather than creating solutions.

Ragusa could have easily found an excuse to blame its problems on the lack of national support. Indeed, the Sicilian province ranks next to last among Italian provinces in physical infrastructure. Ragusa is the only province in Italy without a single kilometer of highway. This is particularly challenging for a region where 90 percent of goods are moved by truck, due to poor railroads, and especially for an economy based on tourism and the export of perishable agricultural products. But Ragusa long ago moved beyond excuses to executing its own plans for revitalization.

So how does a locale or region rise to the occasion instead of falling into disarray? To begin with, people who exercise leadership recognize that in their city and surroundings they have a concentration of activities to compete globally on their own. As we mentioned in the introduction, cities and their connected surroundings are a prerequisite for global competition. As firms mutually evolve and specialize in cities (Porter, 1990), they enjoy the benefits of decreasing costs, labor market pooling, highly specialized production, knowledge accumulation through learning-by-doing and learning-by-watching, and spillover value provided by workers sharing (or poaching) ideas across corporate or institutional boundaries.

Other benefits of cities are dynamism, an increased scale of demand, and concentrations of culture with greater economic significance. Dynamism stems from the process of ‘creative destruction’, as described by Joseph Schumpeter. It also stems from social relationships that promote the adaptation and creation of specialized technologies, often via public–private R&D partnerships. Increased demand stems from individual preferences that spur larger and diversified markets, per the consumption variety argument (Abdel-Rahman, 1988; Ogawa, 1998). One of those markets is for goods requiring large audiences to be successful, such as main sport events, concerts, and the opera (Glaeser et al., 2001).

The concentration of culture stems from cities as the place culture is created, showcased, commoditized, sold, and enjoyed. The desire by consumers to seek out cultural events with ‘reputation and authenticity’ ties them unavoidably to particular cities (Scott, 1997). New York, London, Paris, Rome, Venice, Florence – tourists are attracted by different aspects such as architectural beauty, history and traditions, recreational opportunities, festivals, and art and music events such as la Luminaria in Pisa3 and the Verdi Opera Festival in Parma.4

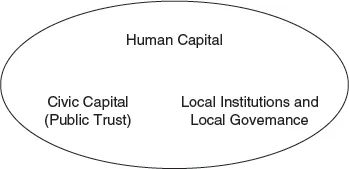

Given the city as an environment for prosperity, local leaders, like those in Ragusa, can start their economic success story by focusing on building human capital, civic capital, and vibrant governance delivered by active institutions at the local level. For a representation of this idea, see Figure 1.1.

This is a new perspective playing on an old theme: As noted by Dani Rodrik (2005), ‘growth-enhancing policies shall be context-specific’. Every locale – Ragusa in Italy, Regensburg in Germany, Rio in Brazil – has to leverage its strengths in its own way. Every locale starts with a different deck of economic and social cards. It inherits civic capital from previous generations and the social environment. It inherits a locale’s unique circumstances – sunny weather, unique markets, trading networks, universities, an educated workforce, and so on. It also inherits local diverse institutions that reflect unique histories. Dealt this hand, local leaders must create, on their own and with these resources, competitive and comparative advantages to compete globally.5

Figure 1.1 The makings of renewed local economic development

We start our story of how to spur local development by stressing human capital. To determine their destiny, local and regional leaders need to nurture a workforce that has both scientific and technical knowledge – in Ragusa that might mean both people who can figure out the right carbon-dioxide levels to best grow hothouse tomatoes and people who can install greenhouse ventilation systems to obtain those levels. They also need to nurture a workforce that has both general and specific skills – in Ragusa’s case, the knowledge of global tomato-market dynamics and the means to get ripened tomatoes on store shelves in those markets. This requires, for example, tailoring vocational training to be sure the locale doesn’t have too much or too little of the skill needed. Ultimately, leaders must monitor local schools and universities to balance the creation of ideas with the transformation of them into advantages that will differentiate the locale from all others.

Along with this nurturing of human capital is the responsibility to build and preserve civic capital, or the elements of public trust. Mutual confidence is invaluable in creating economic vitality and dynamism. Indeed, an environment rich in mutual confidence tends to show low levels of corruption and minimal demand for more regulation. A large reservoir of civic capital – public trust, reciprocal cooperation, and a sense of community – differentiates a locale just as powerfully as workers who increase productivity, favor innovations, and promote better styles of management.

Along with the responsibility to nurture human and civic capital comes the interrelated job of nurturing effective governance through local institutions. Governance should reflect a broad system of rules and beliefs generally accepted at the local level. These rules and beliefs directly affect the economic vitality of a region. Socially efficient institutions favor mechanisms to better coordinate economic success. They work against cronyism, patronage, political bargaining, and other forms of clientelism and rent-seeking that allocate resources in an inefficient manner. When the formal and informal rules by which local institutions operate contribute to welfare-enhancing activities, they facilitate the success of a renewed economic strategy.

Nurturing human capital

For what reasons do human capital, civic capital, and well-governed institutions deserve emphasis as the first agenda items for local and regional leaders concerned with growth? Simply put, without them, leaders cannot set apart their regions as robust competitors in today’s globalized, knowledge-driven economy. Well-governed institutions, human capital, and civic capital together provide the rich soil from which a locale like Ragusa reaps a harvest of ample economic growth. This soil, if it does not remain rich in nutrients, can blight economic vitality.

Let’s start with one of the three components of that soil, human capital, which ranks among the most important nutrients of economic growth. According to research by the World Bank (2011), educated people are more employable, able to earn higher wages, cope better with economic shocks, and raise healthier children. Time spent in school, vocational training, and acquiring technical and scientific knowledge contribute to so-called ‘private’ returns, such as higher labor-force participation and productivity, as well as to ‘social’ returns such as pecuniary and nonpecuniary externalities. Pecu...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Preface and Acknowledgments

- About the Author

- Introduction: Rising to the Occasion

- 1 Building Assets of Local Development

- 2 Unleash and Stimulate Entrepreneurial Creativity

- 3 Foster Innovation and Research

- 4 Leverage Cultural Resources and Creativity

- 5 Make the Most of Cultural Diversity

- 6 Champion Social Mobility

- Conclusion: New Leaders, New Growth

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index