![]()

1

Justice Reinvestment: A Response to Mass Incarceration and Racial Disparity

In little over a decade, the concept of justice reinvestment has captured the imagination of communities, the actors in the criminal justice system and legislatures alike in a range of Western countries. With its promise of reduced spending, decarceration and improved public safety, justice reinvestment emerged at a unique point in time as a reaction to mass incarceration. In the USA, and increasingly elsewhere, a combination of fiscal, political and societal conditions are favourable to the emergence of strategies of penal reduction, including justice reinvestment, to an extent not seen since the 1970s.

The evolution of the practical implementation of justice reinvestment has differed significantly in the UK and Australia in comparison to the USA. Whereas the approach in the USA has concentrated on legislative reform and technical assistance measures, the UK model has adopted a ‘payment by results’ (PbR) approach. By comparison, the embrace of justice reinvestment in Australia to date has been distinctive, focused on a non-government and community-driven approach. However, what is common across all three countries is the recognition that traditional criminal justice policies are failing and are disproportionately failing vulnerable groups.

This chapter examines the emergence of justice reinvestment in the USA, the UK and Australia. Tracing the concept from its origins, this chapter locates the birth of justice reinvestment initially as a reaction to mass incarceration and racial disparity, through its early development in the USA and its progression towards the JRI. Further, it briefly considers the adaptation of the principles of justice reinvestment to suit the UK context before canvassing the momentum building towards justice reinvestment in Australia to date.

Justice reinvestment has come to mean many things to many people. As the story of justice reinvestment is a mere 12 years old, it is still a work in progress. This chapter begins by looking back at key moments during the history of justice reinvestment as a means of grounding the discussion to come and contextualising the analysis of the portability of the concept.

A term is coined

Justice reinvestment is a term that owes its origins to Susan Tucker and Eric Cadora. In an article first published in Open Society, Tucker and Cadora (2003: 3) lament the ‘cumulative failure of three decades of “prison fundamentalism”’ and argue for a place-based approach ‘driven by the realities of crime and punishment’. In an oft quoted passage, Tucker and Cadora (ibid.: 2) assert:

This sentiment has resonated widely. As Austin et al. (2013: 1) explain, ‘the intent was to reduce corrections populations and budgets, thereby generating savings for the purpose of reinvesting in high incarceration communities to make them safer, stronger, more prosperous and equitable’. However, it is important to acknowledge that Tucker and Cadora intended justice reinvestment to generate change well beyond the cost saving to taxpayers. As the authors state, ‘[i]t is also about devolving accountability and responsibility to the local level. Justice reinvestment seeks community level solutions to community level problems’ (Tucker and Cadora, 2003: 2).

An important inspiration for the concept of justice reinvestment was the research conducted by Cadora, Clear, Gonnerman, Kurgan and others identifying ‘million dollar blocks’: literally city blocks in locations such as Brooklyn where the state was spending a million dollars incarcerating the residents (Cadora, 2008; Clear, 2012; Gonnerman, 2004; SIDL, 2009). The focus on geography evident in this analysis of blocks in Brooklyn and elsewhere, is demonstrated in Tucker and Cadora’s (2003: 3) assertion that ‘[a] critical component of reinvestment thinking is stopping the debilitating pattern of cyclical imprisonment’, not least because ‘[t]he “coercive mobility” of cyclical imprisonment disrupts the fragile economic, social and political bonds that are the basis for informal social control in the community’. Ultimately, as Susan Tucker explained in an interview, ‘we were really looking for some kind of mechanism that would in a sense depoliticise the issue of mass incarceration’.

The context of mass incarceration in the USA

Despite what appears to be recent stabilisation, a more than fourfold increase in the prison population nationally since 1975 has left imprisonment and incarceration levels, both in raw numbers and rates in the USA, at historic highs (Green and Mauer, 2010: 2; Tonry, 2014: 525). This exponential growth in incarceration led to the crossing of the dubious milestone of one in 100 Americans being imprisoned by the end of the first decade of the millennium (Pew, 2008: James, Eisen and Subramanian, 2012: 821).

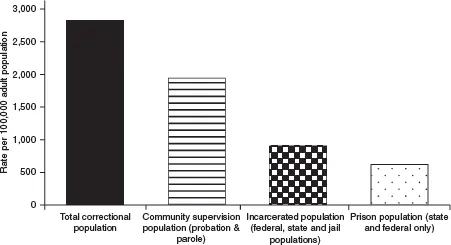

On 31 December 2013, 6,899,000 adult residents in the USA were under some form of supervision through the criminal justice system. This number includes probation, parole, prison and jail (Glaze and Kaeble, 2014; 1). Of those, approximately 1,574,700 were detained in state and federal prisons and a further 731,208 in local jails (Carson, 2014: 1–2; Minton and Golinelli, 2014). These numbers, converted into rates of incarceration per 100,000 of the US adult population, are represented in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 US Incarceration – Rates of supervision comparing total correctional population, with offenders subject to community supervision (probation and parole), and federal, state and jail populations in 2013

Source: Authors’ graph (Carson, 2014: Table 5; Glaze and Kaeble, 2014 Table 2)

For a cross-jurisdictional analysis it is important to understand what the terms jail, prison, parole and probation mean in the USA. A small number of US jurisdictions are unified, which is similar to the position in Australia, where there is no distinction drawn between prisons and jails. However, generally:

•Prison refers to state- or federal-based custody

•Jail denotes local- or county-level custody

•Probation is court-ordered supervision, as an alternative to full-time custody

•Parole means supervision in the community, usually after a term of full-time custody.

The distinction between the term prison and jail is an important one in the US context. Prison populations refer to offenders sentenced under state or federal regimes. State prisons almost exclusively house people serving state sentences. The terms ‘sentenced prisoners’ or ‘imprisonment’ usually refer to offenders sentenced to prison (state, federal or both) for a term of more than one year (Carson, 2014: 1).

Local jails operate at the local or county level. They house primarily pretrial detainees and locally sentenced inmates convicted of minor offences. However, the jail population can also include state-sentenced inmates awaiting transfer to a state prison, people on probation and/or parole who have allegedly violated their supervision orders, accused or sentenced persons from other jurisdictions due to the unavailability of beds, and immigration and customs enforcement detainees (Subramanian et al., 2015: 6–7).

Offenders subject to probation or parole are supervised in the community. Offenders on probation serve their sentence in the community as an alternative to full-time custody. Offenders on parole have generally already served a period of full-time custody and have been conditionally released into the community. However, the latter group can also include persons sentenced to a term of supervised release. Some offenders can be at the same time serving separate probation and parole sentences (Herberman and Bonczar, 2014: 2).

Thus, as Simon (2012: 28) rightly suggests, mass incarceration is a more appropriate phrase as it incorporates populations held in US jails and thus can better ‘facilitate cross-national comparison’ with unified jurisdictions.

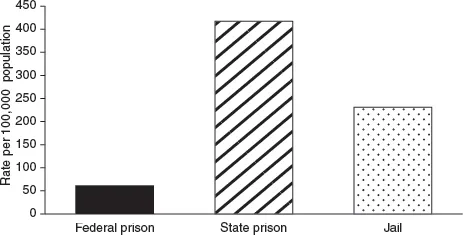

In 1973 the imprisonment rate, which counts state and federal prisoners only, was 150 per 100,000 (Tonry, 2014: 525). In 2013, the imprisonment rate was 478 per 100,000 of the whole US population. This comprises a rate of 61 per 100,000 for federal prisoners and 417 per 100,000 for state prisoners, as demonstrated in Figure 1.2 (Carsen, 2014: 6).

The rate of imprisonment for the US adult population is 623 per 100,000 (Carson, 2014: 6). However, the rate of incarceration, which includes jail populations as well as state and federal prisoners, for the adult population in 2013 was 910 per 100,000, which represents a slight decrease from a peak rate of 1,000 per 100,000 in the years 2006–08 (Glaze and Kaeble, 2014: 4). (See Figure 1.1)

Nevertheless, these statistics do not present a true portrait of incarceration in the USA as they are merely a snapshot of the levels of incarceration on a particular day. In fact, such statistics can dramatically under-represent the true numbers of people entering some type of custody each year. This is best demonstrated by reviewing the jail population. Since 1983, the number of people entering jail has doubled to 11.7 million admissions in 2013. Therefore, while there were 731,208 people in jail on a single day in 2013, nearly 12 million people cycled through jails throughout the USA in that same year (Subramanian et al., 2015: 7; Minton and Golinelli, 2014: 6).

Figure 1.2 US Incarceration – Rates of custody comparing federal, state and local jail populations in 2013

Source: Authors’ graph (Carson, 2014; Table 5; Minton and Golinelli, 2014; Table 1; Glaze and Kaeble, 2014: Table 2).

Difficulties also surround the collection of data for mentally ill or cognitively impaired persons in contact with the criminal justice system. An estimated 25 per cent of the US correctional population has a ‘severe’ mental illness; and it has also been estimated that 56 per cent of state prisoners, 45 per cent of federal prisoners, and 64 per cent of jail inmates have a mental health problem (Kim, Becker-Cohen and Serakos, 2015: 1, v).

The story of mass incarceration

The story of the dramatic rise in incarceration in the USA from the 1970s is one that has been told in detail elsewhere (Garland, 2001a; Drucker, 2011; Tonry, 2014; Alexander, 2012; Cunneen et al., 2013).

David Garland (2001a: 1) first used the phrase ‘mass imprisonment’ in 2001 to characterise what he saw as a unique development in imprisonment in the USA from the mid-1970s onwards: a ‘phenomenon ... that has no parallel in the Western world’. Mass imprisonment, according to Garland (ibid.: 1–2), has two defining features:

Mass imprisonment, he explains:

Thus, a key feature of Garland’s (2001a: 2) description of mass imprisonment as a ‘systemic imprisonment’ is, as Cunneen et al., (2013: 141) explain that, ‘penal culture extends well beyond the prison gates to form part of the defining social conditions of being young, black and male in the USA, the UK, Canada, New Zealand and Australia’.

While the original conception of mass imprisonment as defined by Garland (2001a: 1) clearly entails ‘the social concentration of imprisonment’s effects’ on selected, usually racialised groups, some commentators suggest that the term might (wrongly) imply that the risk of incarceration is uniform (Simon, 2012: 28; Cunneen et al., 2013: 3–4). Wacquant coined the term ‘hyperincarceration’ in order to place class and race at the forefront of the mass incarceration debate. Thus: