![]()

1

Banking Crises and Restructuring Tools

Małgorzata Iwanicz-Drozdowska

This chapter presents a brief history of banking crises and restructuring tools, with a particular focus on the recent global financial crisis (GFC). There always are questions about the causes of turmoil in the financial markets; therefore, the chapter explains how the current crisis is different from the previous ones. The conclusions from the research confirmed that the main causes remained the same all the time; however, the environment in which banks operate has been changing dynamically. A critical factor during the GFC was the contagion effect. In past crises, the most common restructuring tool, associated with government bailouts, was recapitalization (in addition to liquidity support), which allowed most banks to survive.

1.1 Short history and the scope of the analysis

Banks always have faced the threat of losing their safety and soundness because of the way they operate as entities that collect deposits and grant loans, risking the default of the debtor. According to G. Caprio and D. Klingebiel (1996), the first banking crisis occurred in Rome in 33 CE. Until the current global financial crisis, the Great Depression of the 1930s was the most severe breakdown in the banking (and financial) sector.

Political and academic analyses of the causes of the ongoing global financial crisis indicate irregularities in the banking sectors of many countries. One of the key irregularities was excessive lending and the corresponding inappropriate risk management, including risk assessment in the securitization process (Caprio jr. et al., 2008).

One may distinguish three waves of the global financial crisis. In May 2006, Merit Financial Inc. was the first US brokerage firm to go bankrupt, while in August 2006, default rates for subprime loans increased. Subsequent bankruptcies1 of brokerage institutions began in early 2007. The failure of New Century Financial was particularly noteworthy. Because of the American market’s significant global role, the problems occurring in the United States began to spread to other countries and cause contagion. In July 2007, Bear Stearns announced that its two hedge funds investing on the subprime market had nearly lost their value. In July 2007 – beginning of the global financial crisis – financial institutions gradually started to reveal problems with their collateralized debt obligations, or CDOs. One of the first was Swiss UBS. The trouble started to spiral and other institutions declared significant profit falls (including Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs, Bear Stearns, Citigroup, Merrill Lynch, Bank of America, Barclays and HSBC) or serious financial problems (including IKB Deutsche Industrie Bank and Northern Rock). In March 2008, Bear Stearns lost access to short-term financing and ended up being taken over by JP Morgan in May that year.

In Europe, the first wave of the 2007 crisis did not wreak too much havoc on financial markets. But the second wave of the crisis, beginning with Lehman Brothers’ failure, led to a slump in the banking sector and other segments of the financial markets because of losses from exposures to Lehman Brothers, but most of all, because of the loss of trust among the market players. The third phase of the crisis dates to the second quarter of 2010, when Greece’s financial problems became evident. At that time, the banks started to suffer negative consequences of keeping in their portfolios securities issued by the governments of southern European countries.

Although the Great Depression and the current global financial crisis are historically the two greatest breakdowns in the banking sector, banking crises have occurred often. According to IMF statistics, there were 124 banking crises between 1970 and 20072. In order to specify the number of crises, excluding the ongoing global financial crisis, we would have to exclude two cases taken into account by the IMF economists – the United Kingdom and the US (2007). As a result, in the 1970–2007 period 122 banking crises were identified (Laeven and Valencia, 2008, p. 5).Before the outbreak of the current global financial crisis, banking crises occurred in 12 EU countries, including nine in Central and Eastern Europe during the 1990s. (These were the so-called transformation crises – Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Lithuania, Latvia, Poland, Romania and Hungary). Banking crises occurred earlier in Finland, Spain and Sweden.

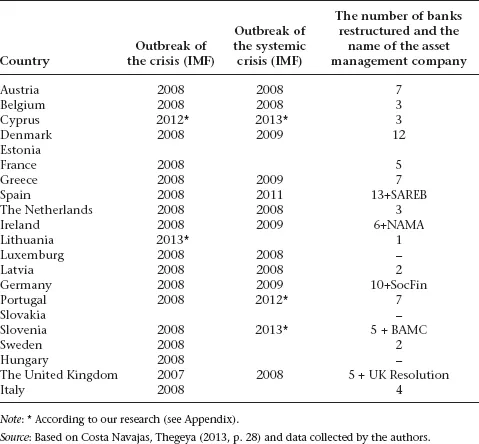

According to the data gathered by the IMF economists (Costa Navajas and Thegeya, 2013, p. 28) over the 2007–2011 period one may identify 11 systemic banking crises in EU countries and additional six crises in other countries (Iceland, Kazakhstan, Mongolia, Nigeria, Ukraine and the United States). This number should be increased by the cases of Cyprus (2012–2013), Portugal (a systemic crisis since 2012) and Slovenia (a systemic crisis since 2013)3. In total, there have been 14 systemic banking crises in EU member states since 2007.

Table 1.1 The list of banking crises in EU countries from 2007 to 2013

In our analysis, we focus on the banks in EU countries (excluding Croatia, which, at the start of the financial crisis, was not a member state). Our study has covered 95 banks4 from 17 EU countries that suffered a systemic crisis or disturbances on a smaller scale that still required government interventions, including the state aid procedure. Additionally, we have analysed five institutions5 created during the crisis to manage bad assets6. Our analysis of the 14 systemic crises does not explicitly include Luxembourg. The issues of that country’s banking sector resulted from ‘importing’ problems from Iceland and from cross-border operations of two banks from the Benelux states (Dexia and Fortis), whose restructuring was co-financed by the government of Luxembourg.

We also have identified cases of bank restructuring in countries that did not suffer systemic crises – France, Lithuania, Sweden and Italy – and we have included them in our analysis. We have not analysed the case of Hungary. The problems occurring there were mainly political and they affected all banks that had granted loans in Swiss francs7. Our analysis has not addressed the consequences of the financial crisis in Iceland for banks and EU countries. Some of them (such as Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg and the UK), through paying deposits to customers, were forced to allocate funds to resolve problems related to branches and/or subsidiaries of Icelandic banks. The major obstacle to analysis is the lack of financial data for those Icelandic institutions that contributed to the problems in EU countries.

1.2 Causes of banking crises – literature review

Over the ages, the main causes of bank failures have changed little. However, financial and organizational innovations undoubtedly make the same cause (for instance, a bad credit policy) have a different impact (usually stronger as the importance of financial operations is greater in the economy) and have a different scope (frequently global). Laeven and Valencia in 2008 described a systemic banking crisis as characterized by, a large number of defaults in the financial and corporate sectors. This results in the increase of non-performing loans and the exhaustion of all or most of the aggregate banking system capital. Massive financial problems on the microeconomic level generate a systemic problem. The decrease or, in extreme cases, exhaustion of banking system capital, requires public authorities to intervene to ‘repair’ the banking sector. There is a strong correlation between the causes of banking crises and the causes of bank defaults.

The tide of the global financial crisis recalled the financial instability hypothesis of H. Minsky (Minsky, 1992, pp. 6–7). Unlike other approaches, this hypothesis treats banking seriously as a profit-seeking activity, which is possible due to the introduction of innovation. H. Minsky distinguished three income-debt relations: hedge financing, speculative financing and Ponzi financing. (The last was named after the founder of the first financial pyramid scheme.) Hedge financing allows the borrowers to repay their debt out of their cash flows. In speculative financing, cash flows are not sufficient to repay the entire debt, but the borrowers may issue new debt or roll over their loans. Speculative borrowers show profits that stress their ability to repay their commitments. Ponzi borrowers do not generate sufficient cash flows to repay their debt or even the interest. Repayments may be made upon the sale of assets or by new borrowing, usually at a higher interest rate. H. Minsky used these three forms of financing to explain both economic stability and instability. When hedge financing dominates, the economy may be in balance. Otherwise, the balance is disturbed. Additionally, after a longer period of economic prosperity, hedge financing is given up, which causes instability8. Operations of banks are procyclical, which should be attributed to, among other things, managers’ approach to risk-taking. During the periods of prosperity, managers concentrate on increasing credit (and investment) activity, especially when prior transactions had proven profitable. This frequently results in a too liberal risk-taking approach, including the loosening of standards of creditworthiness assessment. According to Minsky’s terminology, this represents a move away from hedge financing. Prosperity ends at a ‘certain’ moment and then some customers may fail to fulfil their commitments, which generates losses for the banks. Afterwards, the bank managers apply more restrictive standards when assessing their customers’ creditworthiness, which suppresses increases in lending and makes loans less available in the economy. After some time, the managers change their approach to taking risks and liberalise the rules set earlier. Bergel and Udell (2003) named this phenomenon ‘institutional memory.’ Further, extensive research is required to determine how much profit and loss drive managers’ behaviours, as well as the role of behavioural factors.

Earlier analyses of causes of crises (Iwanicz-Drozdowska ed., 2002; Lindgren et al., 1998; Ostalecka, 2009) pointed to such basic sources as:

•bad policies pursued by banks, mainly with regard to credit risk;

•gaps in regulations and supervision, which allowed for taking excessive risk;

•supervisors’ delayed interventions;

•excessive optimism of market players.

In one of the first papers to analyse the current global financial crisis, the authors enumerate the following main causes (Dell’Ariccia et al., 2008, p. 8):

•more liberal requirements for borrowers due to the dynamic growth of the credits;

•significant, mainly speculative, growth of real estate prices;

•banks’ growing interest in the sale of receivables and securitization, which in consequence led to the easing of the lending policy;

•easing of the monetary policy conditions and keeping low interest rates for long periods.

Here follows a brief review of the literature on the causes of crises and the contagion effect. The contagion effect has been treated as a separate issue because of the important role it has played in the ongoing global financial crisis.

Klomp (2010, pp. 72–87) analysed causes of banking crises and pointed to differences in comparison with prior studies. His literature review comprised, among other things, the variables applied in the studies and the methods and the scope of the analysed cases, as presented in Table 1.2. Klomp conducted research on the period preceding the current crisis, 1970 to 2007, and on 110 countries (with 130 crises). The major differences compared to earlier studies involved application of different estimation techniques, and addition of independent variables that took into account such differences between the countries as the quality of the institutional environment, the financial regulations, independence of the central bank, history of democracy, instability of the government and instability of the regime. Klomp also introduced additional macroeconomic variables. In his conclusions, Klomp argued that the causes of banking crises are different, although one may identify frequently occurring variables, such as increased lending activity, GDP growth and real interest rates. However, none of these variables was significant in more than 60 per cent of crises covered by the analysis. The probability of crisis increased with the growing globalization and the growing ratio of M2 to foreign currency reserves. Klomp also identified differences in the impact of individual variables depending on the level of the economic development and differentiated between a systemic crisis and an ‘ordinary’ crisis. The three most important variables – the growth of lending activity, the GDP growth and the real interest rates – point to the contribution of loans flowing into th...