This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book examines key issues and policy concerns relating to fiscal sustainability and competitiveness in European and Asian economies. In addition to estimating the extent of fiscal capacity or lack thereof for these economies, the authors supplement the empirical analysis with country case studies.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Fiscal Sustainability and Competitiveness in Europe and Asia by R. Rajan,K. Tan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Public Finance. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Overview

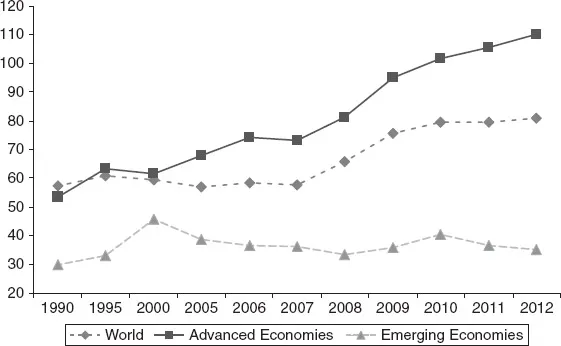

Over the past two decades the fiscal positions of many advanced economies have deteriorated rather precipitously, leading to ever-growing levels of public debt (in absolute terms and as a share of GDP) and mounting concerns about debt sustainability. The ratio of gross government debt1 to GDP for advanced economies was 60 per cent in 2000 and peaked at about 110 per cent in 2012.2 In contrast, the public debt-to-GDP ratio for emerging market economies has remained stable since 2005, ranging from about 35 to 40 per cent (Figure 1.1).3

While some of the abrupt deterioration of the fiscal positions in the advanced economies is no doubt cyclical due to the Great Recession (the gross public debt of advanced economies was just under 75 per cent of GDP at the end of 2007), there have been structural reasons behind it as well. In particular, tax revenues as a share of GDP for the advanced OECD economies hovered at around 35 per cent between 1995 and 2007 before they started falling because of the recession.4 This compares favourably to many emerging economies, a number of which continue to struggle with leaky and narrow tax bases. In addition, the problem in advanced economies has been the sharp rise in government expenditures. Even before the global financial crisis, government expenditures were around 38 per cent of GDP in 2001, reaching nearly 40 per cent in 2007 at the onset of the crisis, before jumping up significantly to a peak of 45 per cent in 2009 due to the stimulus and fiscal stabilisers (IMF 2013a). However, because of the fiscal consolidation measures taken in advanced economies since then, the general government expenditure as a share of GDP started gradually declining and stood at 42.5 per cent in 2012.

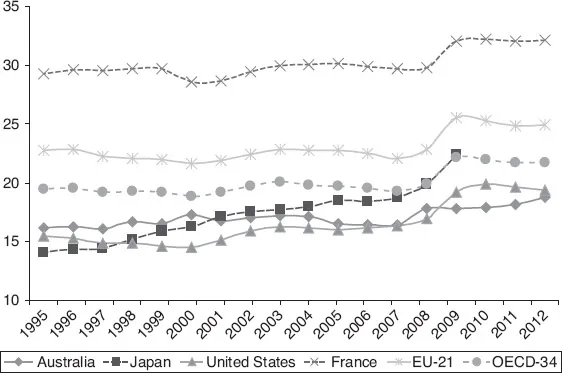

Broadly, about half of these expenditures relate to social expenditures, including public pensions and public health expenditures (Figure 1.2).5 Given worsening demographics in advanced economies, there will inevitably be upward pressure on such expenditures, making fiscal consolidation all the more imperative. Reinhart and Rogoff (2011, 3) note that the “combination of high and climbing public debts ... and the protracted process of private deleveraging makes it likely that the ten years from 2008 to 2017 will be aptly described as a decade of debt”. While financial markets have already passed the verdict that the fiscal positions of some European countries are not sustainable (notably the GIPSIs),6 there is a vigorous debate on how to undertake the required fiscal adjustment in many of the other economies in light of the Eurozone crisis.

Figure 1.1 Gross government debt (% of GDP)

Note: Figures for analytical country groupings are PPPGDP-weighted averages. All the figures and tables for Europe and Asia are based on a combination of OECD, Eurostat, IMF World Economic Outlook and fiscal monitor databases, unless and otherwise specified.

Source: For a detailed list of definitions and the sources for each figure and table, see Rajan, Tan and Tan (2014).

Figure 1.2 Public social expenditure in selected OECD countries, 1995–2012 (% of GDP)

This monograph examines issues relating to fiscal sustainability, competitiveness, and external balances in a set of European and Asian economies. Chapter 2 explores definitions and concepts relating to fiscal sustainability and estimates the extent of fiscal space or lack thereof for a set of European and Asian economies. Chapters 3 through 6 supplement the empirical analysis in Chapter 2 with case studies of the various economies. The aim is to examine the various country experiences using a broadly similar template subject to available data. Chapter 7 draws a set of conclusions based on the case studies and crises experiences in the two regions.

In Europe, we examine two sets of countries – selected Scandinavian countries, including Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden (Chapter 3), and the crisis-hit Eurozone economies that include Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Spain, and Italy (Chapter 4). In Asia, we focus on Japan, South Korea, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and China as well as India (Chapter 5) along with a set of Southeast Asian economies, namely, Singapore, the MIT economies (Malaysia, Indonesia, and Thailand) and the Philippines (Chapter 6).

2

Fiscal Sustainability and Competitiveness: Definitions, Issues, and Measures

2.0 Introduction

This chapter explores the issue of fiscal sustainability and the nexus between public debt and export competitiveness with applications to selected European and Asian economies. The next section briefly outlines some analytical concepts relating to fiscal sustainability as well as their practical limitations. Section 2.2 directly links the issue of export competitiveness with fiscal sustainability and focuses on empirical estimates of debt thresholds. Section 2.3 uses the estimates derived to ascertain the extent of fiscal space or lack thereof in a set of country case studies in Europe and Asia. Section 2.4 concludes.

2.1 What is fiscal sustainability?

There is no single definition of or theoretical benchmark for fiscal sustainability (FS), though it broadly refers to limits on government debt or debt accumulation. At a general level, the IMF (2011a, 5) notes that a “fiscal policy stance can be regarded as unsustainable if, in the absence of adjustment, sooner or later the government would not be able to service its debt”. The most commonly used definition is that the government cannot engage in a Ponzi scheme (i.e., borrowing just to meet interest payments, leading to a ballooning of debt). Buiter (1985) and Blanchard et al. (1990) establish an intertemporal fiscal solvency criterion that essentially requires that the present discounted value of all future primary surpluses equal the initial level of public debt (or some target level). However, such types of intertemporal solvency criteria allow a government to run persistent deficits for a prolonged period as long as there are surpluses at some time in the future and as long as the debt issuance does not rise faster than the real interest rate on debt (transversality condition). These criteria, while useful analytically, are rather loose and offer little by way of policy guidance as to specific limits on debt accumulation.

2.1.1 Long-run sustainable debt

At an operational level, FS often refers broadly to how public debt evolves over time and where debt stabilises as a share of GDP. Based on this definition, one derives the result that the debt ratio will continue to rise indefinitely as long as the real interest rate exceeds real GDP growth unless the primary budget is in sufficient surplus.1 Conversely, if a country is expected to run a primary deficit (thus adding to the stock of debt), then the economic growth rate must exceed (real) interest rates in order for the debt-to-GDP ratio to decrease.2 Thus, for instance, if the historical average interest rate for a decade is 2 per cent, the economy grows at 6 per cent, and primary deficit is 3 per cent of GDP, then the debt-to-GDP ratio ought to stabilise at 75–80 per cent of GDP.3 There are, of course, several problems with this framework – for example, it is a partial equilibrium by nature, assumes that primary balance, interest rates, and economic growth are exogenous variables, and does not incorporate uncertainty, etc.4 Nonetheless, given that it is parsimonious and commonsensical, this formula is quite a useful as a yardstick of FS or, more precisely, as a measure of long-run sustainable debt.

2.1.2 Other methods

Another commonly used operational definition of FS is based on tests to ascertain the univariate statistical properties of individual public finance variables (Hamilton and Flavin 1986; Trehan and Walsh 1991). This strand of the literature tests the stationarity of public debt and the primary balance relative to GDP, with non-stationarity interpreted as an unsustainable policy. However, the problem with such time series approaches is that they are “backward looking” and do not factor in estimates of future revenue and expenditures and also do not offer any guidance about the “fiscal reaction” needed to ensure debt sustainability. To that end, alternative measures include estimating fiscal reaction functions of government; the idea here is to estimate the relationship between a country’s primary surplus and public debt and to test how primary balance responds to changes in public debt (Bohn 1998). In other words, do the fiscal authorities behave in line with a so-called Ricardian fiscal regime and react to debt accumulation, thus suggesting that they care about sustainability of public finances?

In addition, there are other supposed forward-looking measures of FS that forecast future developments of public finances based upon currently available information. A specific type of forward-looking measure is the generational accounting by Auerbach et al. (1999) that not only undertakes long-term projections but also signals FS problems defined broadly to involve the absence of intergenerational fairness. However, these alternative measures are more complicated, more assumption-laden, and are not always easy to operationalise. In addition, all these measures of FS face a similar problem in that their focus is essentially on solvency. They do not pay attention to the possibility of a forced adjustment by markets if creditors decide not to continue financing the sovereign.5

2.1.3 Liquidity measures

Is there a certain debt-to-GDP threshold beyond which a country becomes susceptible to disruptions/painful adjustments?6 This question is tied closely to the concept of “fiscal stress”, which can be broadly defined as a situation reflecting severe difficulties of government funding. To this end the IMF and other institutions have developed non-parametric methods or signal approaches to help alert governments to the possibility of a sovereign debt crisis (for instance, see Berg et al. 2004; IMF 2011a; Manasse and Roubini 2005). Baldacci et al. (2011), for instance, have developed a fiscal monitoring framework that will help in assessing government rollover risk that emerges when a government faces solvency issues. They propose two complementary measures to assess rollover risk: a fiscal vulnerability index and a fiscal stress index. These indices are computed based on a set of fiscal indicators that measure the risk to fiscal sustainability. The list of variables are grouped into three themes: The first relates to current and expected fiscal variables, such as stock of public debt, current and projected primary fiscal balances, and the growth-adjusted interest rate on public debt. The second relates to long-term demographic and economic trends, including spending related to demographic developments. The third relates to examining characteristic...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 Overview

- 2 Fiscal Sustainability and Competitiveness: Definitions, Issues, and Measures

- 3 Nordics

- 4 GIPSIs

- 5 North Asia and India

- 6 Southeast Asia

- 7 Drawing Lessons

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index