This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Full of practical diagrams and maps, as well as international case studies, this book offers a unique and extensively-tested 'GO-STOP Signal Framework', which allows managers to better understand why consumers are not buying their products and what can be done to put this right.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Why People (Don't) Buy by Amitav Chakravarti,Manoj Thomas in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Marketing. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

chapter 1

Three causes

Why successful consumer insights are still a hit-or-miss affair

Executives often attribute marketing mistakes to a lack of customer centricity. The standard refrain is that mistakes happen because managers do not listen to the “voice of the customer.” However, the problem is not so simple.

While not listening to the “voice of the customer” has often landed companies in trouble in the past, this does not seem to have been the case with the companies we discussed in the opening vignettes. Managers at firms such as JC Penney, Ocean Spray and Tata have always focused on the customer’s unmet needs and how their actions might fulfill some of the unmet needs. No one can accuse them of not being customer-centric. Indeed, it is precisely because Ron Johnson heeded the customer’s voice applauding the experience at Apple Stores, and deriding the experience at JC Penney, that he decided to make improvements to the customer experience as the centerpiece of his revival strategy for JC Penney. And it is precisely because Ratan Tata (the chief executive officer (CEO) of Tata) paid close attention to the plight of the Indian bottom-of-pyramid two-wheeler customer that he decided to embark on designing a safe, all-weather and highly affordable car for the masses. By the same token, managers at Ocean Spray had their ears on the ground with respect to the latest consumer trends and preferences, which prompted them to launch the 100-calorie packs of Craisins. So it is hard to implicate turning a deaf ear to the voice of the customer as the main reason for these customer insight errors.

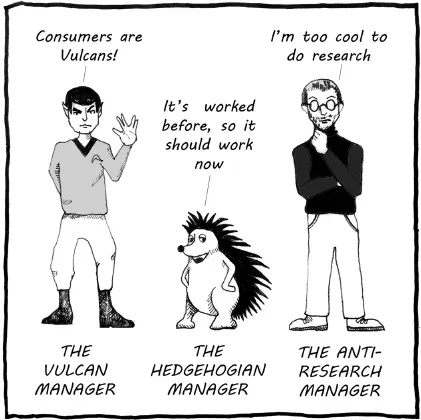

We believe that these glaring mispredictions and this hit-or-miss pattern of consumer insights can be attributed to three major causes: (i) incorrect beliefs about consumer behavior, (ii) a hedgehogian approach to strategic decisions, and (iii) incorrect beliefs about market research.

A word of caution. The next few pages of this chapter might be a little too technical or concept-heavy. However, it is our sincere hope that our readers will bear with these pages. Though a bit complex, this chapter lays a critical foundation that will help readers to understand more easily why the business landscape is littered with consumer insight errors. The rest of the book will be far less technical in comparison.

First cause

Incorrect beliefs about consumer behavior

Our mental models—that is, our beliefs about how things work—shape our thought processes. The accuracy of our predictions, inferences and judgments about the world depend on the validity of our mental model of the world. If an astronomer’s beliefs about the solar system are incorrect, then his predictions about the eclipse are also likely to be incorrect. If an engineer’s beliefs about the properties of a material are incorrect, then his prediction about its tensile strength is also likely to be incorrect. In like vein, if a manager’s beliefs about how the human mind works are incorrect, then his or her predictions about consumer behavior are also likely to be incorrect.

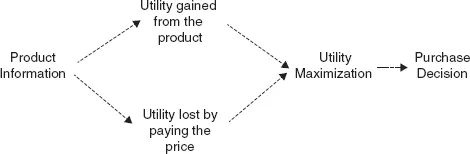

The mental model of consumer behavior among MBAs and managers has been influenced by economics and economists. In academia, for over a century economics has been considered the imperial social science, the noblest of all social sciences. Economists have exerted a strong influence on public policy, business strategy and business school pedagogy. The traditional literature in economics portrays consumers as homo economicus—rational and deliberative beings always making decisions to maximize their long-term utility. As per this utility-maximization model every purchase decision is a trade-off between the utility gained from purchasing the product and the utility lost from the money that is paid to acquire the product. Consumers first assess the utility gained from the product and consider whether it exceeds the utility lost by paying the price of the product. If you were considering buying a $30,000 car, you would proceed with the transaction only if your subjective utility gained from owning the car exceeds the subjective utility lost from paying $30,000. If you are choosing among several cars, you will always choose the car that maximizes your subjective utility. Figure 1.1 summarizes the economic utility-maximization model.

At first blush, this parsimonious utility-maximization model of consumer behavior seems reasonable. Consistent with the predictions of this model, adding more attractive features to a car will make a potential customer more likely to buy the car, whereas increasing the price of the car will make him or her less likely to buy it. The utility-maximization model also yields nice—some would say beautifully precise—graphs of demand and supply. So far, so good!

However, a more careful scrutiny reveals that when it comes to predicting consumer behavior the traditional utility-maximization model and its extensions do not have much descriptive validity beyond some basic economic transactions.1 They are not necessarily incorrect. Rather their predictive validity is quite limited. Neoclassical economic models are useful in explaining why people are less likely to buy when price increases, and why prices tend to decrease when there is competition. But successful marketing strategies are not based on such general and obvious behavioral patterns in the marketplace. Successful marketing strategies are based on latent consumer insights that explain paradoxical consumer behaviors. When it comes to explaining why Apple is such an adored brand despite being more expensive than similar competing brands, or why consumers love “30% off” sale signs even when such signs do not mean much in an era of perpetual discounts, or why economic incentives inhibit instead of encouraging prosocial behavior, the explanations offered by traditional economic models are less persuasive.

FIGURE 1.1 The utility-maximization framework

Enter Mr Spock—the Vulcan

Traditional economic models are more prescriptive than descriptive. That is, these models do not describe actual everyday consumer behavior; instead they characterize how a “rational” consumer ought to behave. Mind you, in economics the word rationality is not used as most people use it in everyday parlance. This is rationality as defined by the mathematical models of economics. If you are a Star Trek fan, then think of Mr Spock, the emotionless extraterrestrial humanoid from plant Vulcan who served as the first officer aboard Captain James T. Kirk’s space ship. Because he can exert complete control over his emotions and mind, and he can perform complex computations in his mind in a jiffy, Spock comes very close to economists’ portrayal of a rational being.2

One doesn’t have to think for long to realize that ordinary earthlings do not behave like Spock. Therefore, their behaviors do not always conform to the tenets of rationality as prescribed in economics.

Here are some illustrative examples. One tenet of rationality is that a homo economicus should have consistent utility for money. For example, a rational consumer should always have more utility from $40 than from $20. So if a rational consumer finds a $20 discount attractive, then he or she should find a $40 discount even more attractive. But real-world consumers often violate this tenet of rationality. If you are like most consumers, then you would be delighted to get a $20 discount on a dress that is usually sold for $100, but would be considerably less excited by a $40 discount on an appliance that is usually sold for $2000. Although everyone knows that $40 can fetch twice the purchasing power, somehow $20 on $40 definitely seems more attractive than $40 on $2000. Clearly, consumers don’t always value $40 more than $20; their valuations are influenced by somewhat arbitrary reference points in their minds.

Another tenet of rationality is that a homo economicus should have reasonably stable preferences for products. Only then can a homo economicus efficiently maximize utility. But this is seldom the case with real-world consumers. Real-world consumers’ preferences for products are hugely influenced by the salient cues in their immediate environment. They learn to spontaneously respond to the cues that they have previously seen in their environment, oftentimes without even being aware of such cues. For example, consumers often use prices and brand names as cues for quality. Extensive work by branding research scholars such as Kevin Keller of Dartmouth attests to the inexorable influence of brands on consumer decision making. Brain-scanning studies have shown that the same wine actually (i.e. physiologically) tastes better when it is priced at $25 than when it is priced at $5. The same energy drink can be actually less efficacious—provide less energy—when it is sold at half the price. For Coca-Cola fans, the same cola—when served in two differently branded packs—seems tastier when it is branded as Coca-Cola than when it is branded as Pepsi-Cola. What these studies tell you is that, unlike the elusive homo economicus, real people do not have stable preferences. Consumers’ preferences, and the utilities that underlie these preferences, are very labile.

Not just the subjective utility of products, even consumers’ subjective valuation of money is influenced by seemingly irrational cues. Home buyers are, paradoxically, more likely to feel that they are paying a very high price for a house when it is listed as $350,000 than when it is listed as $353,465. Even though debit cards and cash are, for all practical purposes, identical modes of payment, consumers spend money more liberally when they spend using debit cards than when they spend cash. Such behavioral patterns are inconsistent with the homo economicus model of consumer behavior, suggesting that economists’ model of a rational consumer might not be very useful in predicting actual consumer behavior. It is not just consumers; researchers such as Adam Alter from New York University have shown that even seasoned decision makers, such as hard-nosed stock-market investors, exhibit the same irrational patterns of behavior.

If managers and public policy formulators work with the assumption that consumers are deliberative and emotionless utility maximizers, then their predictions about consumer behavior are likely to be way off the mark. In fact, many of the consumer insight failures that we will discuss in this book can be attributed to such incorrect conceptions of consumer behavior. Real-world consumers are quick thinkers, relying on fast and frugal heuristics, and emotionally sensitive beings, intrinsically motivated to avoid negative emotions and seek positive emotions. Contrary to the view in neoclassical economics, more and more scholars now believe that the ability to think fast and emotional sensitivity are not necessarily limitations of the human mind, rather, these properties help us to adapt and thrive in new environments. Professors George Loewenstein of Carnegie Mellon and Robert Frank of Cornell University are two of those economists who have highlighted the importance of incorporating the role of emotions in economic models of decision making. They have written extensively about this in the academic as well as popular press. However, while our quick thinking and emotional sensitivity make us the smartest species on earth, it also results in seemingly capricious and irrational behaviors. If you are in the business of predicting consumer behavior—that would include business managers, market researchers, advertisers, public policy formulators and academics—then an appreciation of the roles of heuristics and emotions is a must. Only then can you develop a more descriptive model of consumer behavior.

Consumers are quick thinkers, relying on fast and frugal heuristics

The GO-STOP framework: a preview

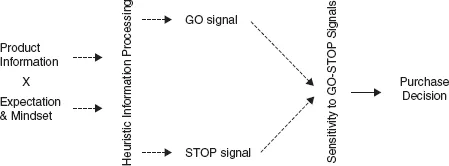

In this book, we present an alternative model of consumer behavior based on decades of research in psychology. Psychology, unlike economics, is more of a descriptive social science and does not portray humans as rational robot-like creatures. The psychological model of human behavior—the homo psychologicus—is not shackled by assumptions of rationality. Instead, psychologists understand the roles of motivational states, heuristic inferences, unconscious mental processes and emotions in adaptive human behavior. The GO-STOP framework of purchase decisions presented in this book builds on the conceptualization and empirical results documented in the cognitive, social and consumer psychology literatures. A schematic depiction of the GO-STOP framework is presented in Figure 1.2.

FIGURE 1.2 The GO-STOP framework

The GO-STOP framework is based on the premise that a purchase decision is driven by two types of brain signals—a GO signal and a STOP signal. A GO signal is a thought, feeling or an unconscious response that energizes the consumer to approach and buy the product. The STOP signal is a thought, feeling or unconscious response that inhibits him or her from spending money on the product. The GO signal activates an approach response whereas the STOP signal inhibits this response. In our GO-STOP framework, it is the interplay between the GO signal and the STOP signal that determines whether or not a product is bought. If the strength of the GO signal is significantly greater than the strength of the STOP signal, then the consumer buys the product. In contrast, if the STOP signal is stronger than the GO signal, then the consumer shies away from purchasing the product.

A purchase decision is driven by two types of brain signals—a GO signal and a STOP signal

There are several important differences between the homo economicus model and the GO-STOP framework, which is based on psychological theories. Let us highlight the four important ones here.

First, this model postulates that emotions play an important role in the activation and regulation of behavioral tendencies. GO signals can be triggered by the anticipation or experience of positive emotional states (although sometimes the GO response can also be triggered by the motivation to alleviate negative emotional states). STOP signals can be activated by the anticipation or experience of negative emotional states such as the pain of parting with money or regret.

Second, the model assumes that these GO and STOP signals could either be based on deliberative thinking or could be triggered by unconsciously activated heuristic rules and mental associations. So consumers might not even be aware that some cues in the environment have activated GO or STOP signals in their brains.

Third, the model posits that the relative sensitivity to GO and STOP signals is not as invariant and stable as economists looking for tractable mathematical models would like it to be. Relative sensitivity to cues that trigger GO and STOP signals varies across people, and even for the same person it can vary depending on the context. Some people tend to be in a benefit-maximization mindset that makes them more sensitive to cues that trigger the GO signals (such as design, quality, prestige and taste). In contrast, some people tend to be in a pain-minimization mindset,3 making them more sensitive to cues that trigger the STOP signal (such as unfair pricing, unhealthy ingredients and risk). Furthermore, the same person is sometimes more sensitive to GO signals (e.g. when she is buying a Hermès Birkin handbag) and sometimes more sensitive to STOP signals (e.g. when looking for the cheapest gas station in her neighborhood).

Fourth, the model stipulates that the GO and STOP signals are not fungible. This is in sharp contrast to the u...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Preface

- Introduction: hit-or-miss consumer insights

- 1 Three causes

- 2 The 100 calories paradox

- 3 Pricing disaster at JC Penney

- 4 Tata Nano, the world’s cheapest car

- 5 When not to discount

- 6 Avoid discordant pricing

- 7 Paying for medicines and Tickle Me Elmo

- 8 Credit cards and obesity

- 9 Why paying people to donate blood does not pay

- 10 Five steps to actionable consumer insights

- Glossary

- References

- Index