eBook - ePub

Managing the Macroeconomy

Monetary and Exchange Rate Issues in India

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Managing the Macroeconomy

Monetary and Exchange Rate Issues in India

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

While offering many growth-enhancing opportunities, India's ever-increasing integration with the world economy has given rise to a host of new challenges in managing the economy. This book provides an up-to-date empirical assessment of some of India's crucial policy challenges pertaining to its monetary and external sector management.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Managing the Macroeconomy by Ramkishen S. Rajan,Venkataramana (Rama) Yanamandra in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Asian Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Macroeconomic Overview of the Indian Economy

1.1 Introduction

Having originated in the advanced economies, the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008–09 spread rapidly to the rest of the world. The impact on the emerging markets, especially those in Asia, though not as severe as that in the advanced countries, was still quite significant. India withstood the crisis initially but could not remain entirely unaffected for long (especially after the collapse of Lehman Brothers) given that it has become quite closely integrated with the rest of the world. It was affected by the GFC through the financial, real and the confidence channels (Patnaik and Shah, 2010; Sinha, 2012). Initially, the Indian financial markets (equity, foreign exchange and credit) were hit by the external shock, though the real sector did not remain immune for long, as reflected in the deceleration in growth from a high of around 9 per cent before the crisis to 5 per cent in 2013 (MoF, 2012; Subbarao, 2009; WDI, 2014). Despite being affected by the GFC, India was able to bounce back relatively quickly mainly because the country’s growth was driven by domestic demand and was less reliant on the export sector for its growth compared to many East Asian economies (Bosworth et al., 2006).

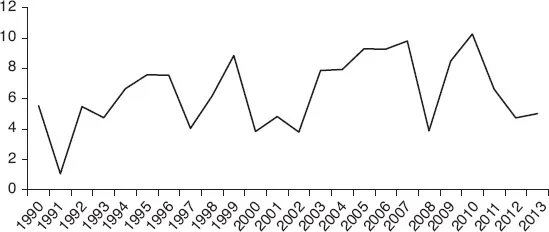

India’s central bank, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), resorted to conventional and unconventional monetary policy measures to deal with the GFC. It tried to augment domestic and foreign exchange liquidity through a sharp reduction in the policy rates as well as the liquidity adjustment facility (LAF), open market operations (OMO) and cash reserve ratio (CRR) (Mohanty, 2011a). The aggressive intervention by the RBI helped assuage the financial markets, and the banking sector returned to some degree of normalcy; real GDP growth quickly bounced back to 8 per cent and 8.5 per cent in 2009–10 and 2010–11, respectively, confirming the V-shape growth hypothesis for India (Figure 1.1) (Mohanty, 2011a; Sinha, 2012; Virmani, 2012). Even though some studies have suggested that Indian business cycles exhibited co-movement with the business cycles in the industrial countries prior to the GFC, India continued to grow despite a slump in the industrial countries (Ghate et al., 2011; Jayaram et al., 2009; Patnaik, 2013).

However, the bounce-back after the GFC was short-lived as growth slowed down to about 5 per cent during 2012–13, with India’s inflation rates and the fiscal deficit (as share of GDP) among the highest for emerging markets (IMF, 2013a). Apart from cyclical and global factors, India’s structural constraints and uncertain policy environment contributed to negative growth-inflation dynamics. One of the main constraints on growth has been “infrastructural bottlenecks,” particularly in the power and mining sectors, which has contributed to a slowdown in industrial growth, in turn causing pressure on the economy as a whole. The policy uncertainties on the tax front, coupled with a loose fiscal policy, reduced foreign investor interest in India and contributed to the slower growth along with growing macroeconomic imbalances (Goyal, 2013a; IMF, 2013a; Patnaik, 2013; RBI, 2013b).1

Figure 1.1 Economic Growth based on gross domestic product (%)

Source: World Development Indicators.

The post-GFC growth slowdown notwithstanding, the macroeconomic situation and challenges faced by India since its liberalisation in 1991 warrants discussion. Section 1.2 will focus on the macro growth story of India. Section 1.3 discusses India’s balance of payment (BoP) dynamics. Section 1.4 focuses on the evolution of monetary policy and the monetary framework and operating procedure of the RBI. Exchange rate regimes, movements and reserve management policies and their impacts are discussed in Section 1.5. The final section provides some concluding remarks. Annex 1.1 presents a note on the fiscal sustainability (FS) of India.

1.2 Background: Indian macro growth story in brief

1.2.1 Growth

Indian growth took off after its economic liberalisation in 1991 (Figure 1.1).2 India started the decade of the 1990s with a BoP crisis. The crisis was caused by weak fundamentals in the economy since the mid-1980s, particularly large fiscal and current account deficits (CAD). The CAD widened in this period due to a policy change of moving away from autarky and import substitution towards export-led growth. Exports started to grow robustly but imports rose even faster, especially due to the rising demand for petroleum products.

From a savings and investment perspective, while gross domestic savings (GDS) rose (from 18.5 per cent in 1985 to 23 per cent in 1990), gross domestic capital formation (GDCF) rose more sharply (20.6 per cent in 1985 to 26 per cent in 1990), leading to growing CADs. The rising CAD could not be met by the concessional finance available to the country, and therefore India resorted to external commercial borrowing (ECB). India’s external debt rose to around 38 per cent of its gross national income (GNI) by 1990, from around 11.5 per cent in 1980. These developments made India vulnerable to external liquidity shocks (Cerra and Saxena, 2002; Mohan, 2008; Saraogi, 2006; Sen Gupta and Sengupta, 2013).

Against the background of growing vulnerability, the trigger for the BoP crisis of the early 1990s was the rise in oil prices caused by unrest in the Middle East (the Iraqi-Kuwait war), which was further compounded by the fragile political situation in India. Remittances declined as a result of the war in the Middle East and so did exports due to a slower growth in the US, which was India’s most important trading partner after the European Union (EU) (constituting around 15 per cent of India’s total exports in 1990–91). These factors led to a downgrade of India by the credit rating agencies, which added to India’s capital account problems and pushed the country to the verge of a default, with international reserves sufficient for only three weeks of imports (Cerra and Saxena, 2002).

However, swift action was taken to resolve the crisis, and within two fiscal years (1991–92 and 1992–93), the country managed to recover smartly from the crisis. India underwent a combination of devaluation, domestic deflation and support from the IMF to deal with the crisis. The Indian rupee (INR) was devalued twice in July 1991 to deal with the withdrawal of reserves so as to instill confidence in the investors and improve domestic competitiveness (Ghosh, 2006). The Indian government initiated a process of economic reforms along with macroeconomic stabilisation. With regard specifically to external liberalisation, the Rangarajan Committee of 1991, which was set up to recommend reforms after the crisis, suggested the following set of policies: encouraging current account convertibility by liberalising current account transactions, selectively liberalising the capital account, focusing on encouraging long-term flows, and discouraging short-term debt and volatile flows (Reddy, 1998). As part of these reforms, Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) was opened up to domestic and foreign firms, while portfolio flows were opened up only to foreigners, ECBs were regulated, volatile elements of flows from non-resident Indians (NRIs) were discouraged and there was a gradual liberalisation of outflows and disintermediation of the government in the flow of external assistance (Shah and Patnaik, 2007).

The reforms undertaken after the crisis led to a change in the structure of the Indian economy. Unlike in many other emerging markets, where the manufacturing sector led the structural transformation, in India the services sector became a major driver of growth, particularly due to the opening of the current and capital account and the rising importance of international trade. This sector contributed to more than 55 per cent of the GDP and thereby to the overall growth of the economy by 2000.3 Despite the move towards services from agriculture, the share of employment in the agriculture sector has not declined commensurate with the fall in the share of this sector, implying declining productivity in the agricultural sector. To sustain the growth that India has achieved so far, it is essential to ensure that labour moves out of agriculture into both the services and manufacturing sectors (Bosworth et al., 2006; Eichengreen and Gupta, 2011; Kotwal et al., 2011).

The period since 1991 can be divided into three phases of growth: (1) 1992–2003, when the country was recovering from the BoP crisis with an average GDP growth of a little less than 6 per cent; (2) 2003–08, a period of high growth for India with average growth rates near 8.5 per cent; and (3) a slowdown triggered by the GFC, when growth slowed to around 6.5 per cent (Mohanty, 2012a; WDI, 2013). Total trade for India as a percentage of GDP tripled from around 14 per cent in 1991 to 42 per cent by 2012. This period also witnessed an increase in capital flows, with net capital inflows more than doubling from around 2 per cent in 1990s to above 4 per cent of GDP during the high growth period of 2004–08. The openness of the Indian economy has been accompanied by an improvement in India’s external position, as the foreign debt to GDP ratio fell from about 29 per cent in the 1990s to around 18.5 per cent by 2010. The debt-service ratio also dropped from 26 to 5 per cent during the same period. Prices remained stable till the beginning of the GFC, with both the wholesale price index (WPI) and consumer price index (CPI) inflation rates declining from an average of around 8 per cent in the 1990s to around 5.5 per cent in the 2000s. However, India has experienced double-digit CPI inflation since the beginning of the GFC and the WPI also increased to over 7 per cent (Mohanty, 2012a; WDI, 2013).

Even though the reforms enacted in the 1990s led to an improvement in efficiency, the growth impacts occurred with a long and variable lag and did not bear fruit until the early 2000s. Several reasons have been identified for this pattern. Most of the reforms enacted during this period, such as the tax reforms, were efficiency-improving and only had lagged effects on growth. Second, after the initial spurt of policy initiatives, reforms started to stall and many distortions severely constrained growth.4 Third, total factor productivity (TFP) followed a J-curve pattern, with an initial deterioration followed by an improvement over the long term. This pattern was due to the adjustment of the distorted prices based on protection to the industries until the 1990s, reduction in capacity utilisation of unprofitable product lines and gestation lags in investment in the newly profitable product lines (Virmani, 2012).

As noted, it was initially assumed that the impact of GFC on India would not be too severe, as Indian growth was mainly driven by domestic demand and also because of the lack of US toxic assets in Indian balance sheets. However, things changed rather dramatically with the collapse of the Lehman Brothers in September 2008. This change was because the crisis, which initially began as a localised sub-prime crisis, soon spread to the different sectors of the economy and countries of the world given the high level of trade and financial integration. For the same reason, India – which was not as severely impacted during the Asian Financial Crisis (AFC) – was impacted more during the GFC as its integration with international markets increased. India’s increased openness is well captured by the ratio of total external transactions (gross current account plus capital account flows) to GDP – an indicator of both trade and financial integration – which went up 2.5-fold from 44 per cent ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 Macroeconomic Overview of the Indian Economy

- 2 Effectiveness of Monetary Policy in India: The Interest Rate Pass-Through Channel

- 3 Understanding Exchange Rate and Reserve Management in India

- 4 Impact of Exchange Rate Pass-Through on Inflation in India

- 5 Rupee Movements and India’s Trade Balance: Exploring the Existence of a J-Curve

- 6 External Financing in India: Sources and Types of Foreign Direct Investment

- Index