eBook - ePub

Cultures of Wellbeing

Method, Place, Policy

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The authors challenge psychological perspectives on happiness and subjective wellbeing. Highlighting the politics of quantitative and qualitative methodologies, case studies across continents explore wellbeing in relation to health, children and youth, migration, economics, religion, family, land mines, national surveys, and indigenous identities.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Cultures of Wellbeing by Sarah White, Chloe Blackmore, Sarah White,Chloe Blackmore in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Global Development Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction: The Many Faces of Wellbeing1

Sarah C. White

Introduction

In her novel Regeneration (1998), Pat Barker presents the following reflection of the neurologist and anthropologist W. H. R. Rivers (1864–1922) on his fieldwork in the Solomon Islands:

I thought I’d go through my usual routine, so I started asking questions. The first question was, what would you do with it if you earned or found a guinea? Would you share it, and if so who would you share it with? It gets their attention … and you can uncover all kinds of things about kinship structure and economic arrangements, and so on. Anyway, at the end of this … they decided they’d turn the tables on me, and ask me the same questions. Starting with: What would I do with a guinea? Who would I share it with? I explained I was unmarried and that I wouldn’t necessarily feel obliged to share it with anybody. They were incredulous. How could anybody live like that? And so it went on, question after question. … They were rolling round the deck by the time I’d finished. And suddenly I realized that anything I told them would have got the same response … it would all have been too bizarre. And I suddenly saw that their reactions to my society were neither more nor less valid than mine to theirs. And do you know that was a moment of the most amazing freedom. I lay back and I closed my eyes and I felt as if a ton weight had been lifted. … It was the Great White God de-throned, I suppose. Because we did, we quite unselfconsciously assumed we were the measure of all things. That was how we approached them. And suddenly I saw not only that we weren’t the measure of all things, but that there was no measure.

(Barker 1998: 212, excerpted)

As at once a neurologist and anthropologist, W. H. R. Rivers seems ideally suited as a guide into qualitative, mixed method, intercultural research into wellbeing. This passage is redolent of the experience of wellbeing as something that ‘happens’ – first interactively, in the stimulation of intercultural exchange, shared conversation, laughter and insight, and second internally, in the release of being de-centred, letting go of the need to judge and assess. At the heart of the episode is Rivers’ recognition of the many ways of being, with his own society no more providing a universal standard than does any other. Striking also is his sense of liberation at escaping the need to ‘measure’. Finally, the sense of dislocation he describes – and embraces – may echo a common experience amongst those who research wellbeing, given the multiplicity of influences on it and the extensive range of its possible interpretations.

This book provides a distinctive collection of empirical studies of wellbeing in diverse contexts, predominantly in the Global South. ‘Cultures of wellbeing’ refers first to diversities in social and cultural constructions of wellbeing, and the need for analysis of and dialogue between them. It further suggests that wellbeing is produced through social and cultural (including political, economic and environmental) practice. In addition, it draws attention to the distinct cultures in different traditions of research, materialised in their routinised practices, techniques and technologies, norms and assumptions, structures and social organisation, and what they hold sacred. This connects to the second major theme, that of method. The concern here is first to challenge the dominance of quantitative methods and illustrate the contribution of qualitative and mixed methods approaches to the study of wellbeing. Second, we emphasise the significance of methodology in shaping all accounts of wellbeing. Both culture and methods relate in turn to the third theme of place. This points to the situated nature of both ‘lay’ and ‘expert’ understandings of wellbeing, and suggests that space and place constitute critical dimensions of wellbeing that deserve much greater attention. Finally, the underlying context of the contributions in this volume is concern for the ways that wellbeing has been, and may be, adopted as a focus in policy and practice.

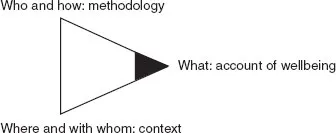

As described below, there are multiple accounts of wellbeing in policy and multiple ways in which the concepts which underlie these are construed. Atkinson (2013: 138) notes that a common response to this diversity is to argue for standardisation, an agreed set of indicators or tools which can be used for constructing authoritative accounts. Our interest in this book is rather different. While different contributors adopt different outlooks and lines of argument, as a collective, the volume proposes a shift of focus away from what wellbeing is, to exploring how accounts of wellbeing are produced. We thus explore the relationships between three key elements of wellbeing research: what is claimed (accounts of wellbeing); how research is undertaken and by whom (researcher identity, cultural and disciplinary assumptions and methods of enquiry producing data and their analysis); and where and with whom the research takes place (place and cultural and socio-economic context) (see Figure 1.1). Practical challenges in generating robust data come together with differences in researchers’ underlying philosophical assumptions regarding epistemology (what can be known and how can it be known, including what it means to do cross-cultural research) and ontology (what actually is, including conceptions of personhood and wellbeing or happiness).

Figure 1.1 The construction of wellbeing knowledge

Each of the chapters thus considers the ways that discipline, method, and/or local culture, socio-economic structure and place shape constructions of wellbeing. Across the volume as a whole, the reification of wellbeing as a ‘real thing’ that people may ‘have’ is resisted. Instead, the argument is advanced that constructions of wellbeing are intrinsically connected to the places in which they are generated and the research methods by which they are produced.

The framework of the book is deliberately comparative. Geographically, the chapters span communities across Africa (Angola, Zambia, Ethiopia and South Africa), South and South-East Asia (Central India and Cambodia), Latin America (Venezuela, Peru and Mexico) and the UK. They draw on different disciplines, including international development, public health, anthropology, sociology and psychology. They focus on different aspects of life: health and physical activity; religion; migration; economic life; family relationships; landmine impact; and the politics of community and identity. Finally, they present and reflect on different methodological approaches, including a national survey, mixed methods, ethnography and a variety of visual and participatory methods. The case studies are organised into two sections. The first five reflect on mixed methods approaches, the second five on qualitative methods. Together, they highlight the complementarities and tensions between quantitative and qualitative methods, issues of reliability in self-reported data, the importance of grounding questions with locally relevant examples, and the scope for person-centred approaches which allow people to talk about what is important for their own wellbeing in their own words.

The purpose of this introductory chapter is threefold. First, it aims to locate this volume in relation to the wider field of wellbeing in policy contexts and the key concepts and methods which this involves. Second, it reflects on the key methodological terms and issues which structure these debates. Third, it introduces the case-study chapters, and describes how they relate to the broader field and how they advance the argument of the volume as a whole.

The field of wellbeing

The ubiquity of references to wellbeing and the diffusion of meanings they bear means any attempt to summarise the field must inspire some trepidation. What perhaps unites contemporary work on wellbeing is the conviction, expressed in many ways, that it is possible to bring wellbeing about intentionally, through a combination of will and technique. Most immediately this is seen in the multitude of publications of the ‘manage yourself, manage your life’ variety promoting self-help psychology, health, spirituality, exercise, diet and lifestyle as a means to self-advancement. But it is also evident in public policy, as voluntary organisations, local councils, national governments and multi-lateral organisations increasingly identify the advancement of wellbeing as their stated objective and statisticians promise new measures which can quantify ‘how people think about and experience their lives’ (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD] 2013: 3).

The diversity, volume and velocity of increase in references to wellbeing suggest a cultural tide that sweeps together a range of different interests and agendas. Its association with health and harmony holds the promise of a release from the tensions of modern life, a hope of re-balancing and revival. Its appeal to ‘science’ – predominantly statistics but more recently neuroscience – reflects the longing for authority and robust foundations for action. Politically, wellbeing gives voice to desires for an alternative, a new moral economy, a counterweight to the excesses of capitalism in a world where the promise of socialism no longer seems credible. Its claim to put people’s own perspectives at the heart of policy-making promises more democratic processes, or even empowerment. Its positive charge offers a corrective to tired old problem-focused policy-making, encouraging people to express their aspirations rather than rehearse their deprivations. Paradoxically perhaps, the stress on personal experience also fits well with the individualist ideologies of late capitalism and their faith in the pursuit of happiness through choice in consumption.

As the paragraph above suggests, much of the energy driving the wellbeing agenda derives from the Global North and those already in a position of relative material advantage. Is it simply a problem of late modernity searching for its soul, a moral reflux in societies which have gorged on excess and sought salvation through consumption? What is the value of this agenda in the Global South, where people surely have more immediate, material concerns to contend with?

This is a serious question. There is without doubt a danger that countries and communities in the Global South have foisted on them an inappropriate agenda derived from elsewhere; the history of international development is full of such examples (e.g. Cooper and Packard 1997, Crush 1995). The chapters in this volume identify several ways in which the dominant approaches to wellbeing need to be challenged or discarded in order to understand lived experience in Asia, Africa and Latin America. There is also a danger that the South – or the East – is invoked in a nostalgic projection of ‘the good life’. Romance with ‘the world we have lost’ is as central to the self-identification of modernity and development as is the disparagement of ‘traditional societies’ (Grossberg 1996). It is precisely because of our sensitivity to such patterns of discursive dominance that we argue the need for more in-depth, qualitative studies which express what wellbeing does – and does not – mean for particular people in particular places, as a way to open up a fuller and more balanced dialogue.

The next section introduces four ‘faces’ of wellbeing in public policy. Before discussing these, however, it is necessary to consider how happiness fits in. There is no clear answer to this. Some writers talk exclusively of wellbeing, some only of happiness and others mix and match between the two. Across the literature as a whole, happiness generally appears as a narrower concept, a component of wellbeing, sometimes identified with ‘subjective wellbeing’ (SWB) (though this fit is far from perfect or consistent, as discussed below). Happiness tends to be identified more with emotion or feelings, and with the individual, while wellbeing may include ‘objective’ elements – such as standard of living, access to health care or education – in addition to ‘subjective’ elements – such as satisfaction with life. Wellbeing has a more established trajectory as a shared objective for community or polity (e.g. Collard 2006). However, happiness is also applied to collectivities, as in the archetypal ‘happy family’, and initiatives like ‘Happy City’ show that happiness is not limited to applications at the individual level (http://www.happycity.org.uk/). In general, happiness is viewed as the more controversial concept, more ideological for its critics, more challenging of prevailing orthodoxies for its advocates. Although our primary orientation is towards wellbeing, we acknowledge that wellbeing and happiness form part of the same cultural complex. Our approach is therefore to explore the ways that different authors use the terms, rather than seeking to draw a definitive line between the two.

Accounts of wellbeing in public policy

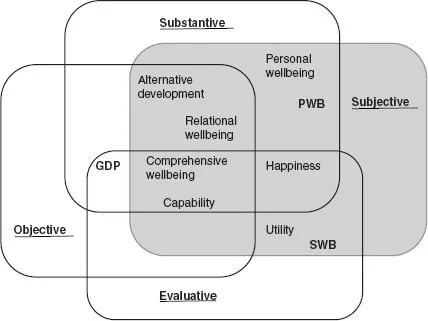

This section identifies four ‘faces’ of wellbeing and happiness in public policy. The first takes a macro approach, using wellbeing to broaden the scope of issues for government attention and specifically to move beyond a sole or primary emphasis on economic growth as the marker of progress. The second focuses on personal wellbeing, aiming to get individuals to take action to promote their own health and happiness. The third concerns the economic concept of utility and involves using subjective measures of happiness or satisfaction to evaluate policy and programme effectiveness. The fourth poses fundamental questions of the current political, economic and social settlements.

The boundaries between these are porous and sometimes fuzzy. The intention is not to draw hard and fast lines between them, but to offer a grid which can be used to map out some key areas of difference in this rather fluid field. The grid focuses particularly on two dimensions. First, does the approach involve subjective or objective dimensions of wellbeing? Second, does it concern the substantive content of wellbeing, or does it primarily involve using measures of wellbeing as a means to evaluate something else? Before proceeding, it is worth taking a little time to explain how I am using these terms.

The division between ‘objective’ and ‘subjective’ dimensions of wellbeing is contested, as discussed below. For the moment, though, we adopt a simple definition. Objective dimensions of wellbeing are those that in principle can be verified by an external observer. Quality of housing, level of education or income would be examples. Subjective dimensions of wellbeing are those that are interior to the person him or herself – thoughts and feelings – where in principle the individual is the ultimate authority (see Gasper 2010, for a more extended discussion). In practice, in social science research, both kinds of data are generally gathered through self-report, either verbally or through a written or online survey. Both kinds of data are thus open to dissimulation, as people say they have one house when in fact they have two, or say they are happy when in fact they are sad. As discussed below and in Camfield (this volume), self-reported data are also very sensitive to the instruments that are used to collect them. This is one of the ways that the simple distinction between objective and subjective begins to unravel.

In public policy, the current interest in wellbeing takes two forms. For some, wellbeing is a substantive concern. This prompts questions like, what does wellbeing mean to different kinds of people and what promotes or inhibits wellbeing? For others, wellbeing, and specifically SWB, is primarily of interest as a means to evaluate something else. In this approach, how happy or satisfied people say they are provides an indicator of the success of a policy or style of government. While some approaches are at one extreme and some at the other, overall this difference is more a matter of emphasis than a complete contrast. A substantive concern with wellbeing may also be the basis of evaluation.

Figure 1.2 maps the four faces of wellbeing in public policy and the key concepts that underlie them on this grid of subjective–objective, substantive–evaluative axes. The darker rectangle identifies the approaches that include a subjective dimension, which are the main focus of this volume. The diagram is explained further in relation to the specific concepts and approaches in the discussion below.

Figure 1.2 Plot of wellbeing approaches in public policy

Comprehensive wellbeing

Comprehensive wellbe...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface

- Notes on Contributors

- 1. Introduction: The Many Faces of Wellbeing

- Part I: Mixed Methods

- Part II: Qualitative Research

- Index