![]()

1

Introduction: Studying Mass Supervision

Fergus McNeill and Kristel Beyens

Introduction

The numbers of adult offenders1 under supervision in the community have grown rapidly in recent decades. In most jurisdictions in and beyond Europe, offenders under supervision (whether as an alternative to prosecution or sentence, as a community sentence in its own right, or as part of a post-custody licence) heavily outnumber those detained in custody. In Germany, for example, whereas the number of prisoners has decreased in recent years, the number of offenders under probation supervision has increased, such that by 2011 there were about 190,000 people under supervision as opposed to 55,000 sentenced prisoners (Federal Statistics Office, 2013 a, 2013b). To take a second example, in March 2013 in England and Wales the prison population was 83,769, while the population of offenders under statutory supervision in the community at the end of 2012 was 224,823 (Ministry of Justice, 2013). Systems and practices of offender supervision have also developed swiftly in Central and Eastern Europe, where nascent probation systems have been a part of post-Soviet-era criminal justice reforms.

Pan-European figures are hard to establish given the wide range of definitions and forms of community sanctions and differences in official recording of their use, but van Kalmthout and Durnescu’s (2008) extensive recent survey suggests considerable expansion of the use of such sanctions in almost all European jurisdictions. Durnescu (2007) estimated that about 2 million people were incarcerated in Europe at the time of his survey, and about 3.5 million were subject to some form of community supervision. The Council of Europe’s Annual Penal Statistics (SPACE I and II) suggested a mean rate of supervision of 179 persons per 100,000 in 2011 across the Council of Europe countries for which information was available.2 The fact that almost all prisoners are (eventually) released, often under some form of supervision, means of course that many prison sentences also involve community-based supervision, whereas the converse is rarely the case. As Robinson, McNeill and Maruna (2013: 322) argue, ‘[t]he vast majority of the “ordinary” (but barely visible) business of supervised punishment therefore plays out daily in probation or parole offices, and in supervisees’ homes, rather than in custodial institutions’.

Leaving aside their increasing scale and reach across jurisdictions, the intensity of supervisory sanctions has also developed considerably in recent decades, extending beyond traditionally rehabilitative measures to include unpaid work; medical, psychological or substance misuse treatment; mandatory drug or alcohol testing; exclusion orders and residence conditions; curfews; house arrest; electronic monitoring and GPS, as well as other innovations. Under criminal law, the use of supervisory sanctions before trial or sentence is increasing too, but supervision has also emerged under civil law (e.g. in the UK’s Anti-Social Behaviour Orders) and in different age-related (and other) boundaries, with greater and lesser degrees of permeability, between the juvenile justice, youth justice and the adult criminal justice systems of different countries, we cannot be very precise or prescriptive about this differentiation. Suffice it to say that we asked our contributors to focus on research about supervision in their adult criminal justice systems.

One driver of this expansion and adaptation, at least in some jurisdictions, is increasing political and public concern about the costs of imprisonment and of reoffending (i.e. offending during or after criminal sanctions). A recent policy paper in the UK estimates that the ‘vicious cycle’ of reoffending by ex-prisoners costs the UK economy £7–10 billion per year (Ministry of Justice, 2010).

The potential role of offender supervision in reducing these costs has become a key interest of contemporary penal policy, particularly in relation to using such sanctions and measures to displace shorter custodial sentences, which have higher costs per day than longer sentences and are typically associated with higher reconviction rates. To give one example of the possible savings, in Belgium the cost of one day under supervision with electronic monitoring is approximately €39. Though electronic monitoring is one of the more expensive forms of supervision, this is a third of the cost of a day in a Belgian prison (approximately €126 per prisoner per day).3 Many argue (somewhat more controversially) that, as well as being much less expensive than imprisonment, community supervision can produce lower reoffending rates.

This remarkable expansion and adaptation, along with the recurring claims of greater ‘efficiency’, ‘effectiveness’ or credibility that have been made for supervisory sanctions, should have ensured that such sanctions became a key focus of contemporary penology in Europe and elsewhere. Yet despite the influence and standing of Cohen’s (1985) Visions of Social Control, it is the growth of ‘mass incarceration’ that has preoccupied scholars, unwittingly allowing the neglect of the parallel development of ‘mass supervision’. This neglect has analytical and practical consequences. It skews academic, political, professional and public representations and understandings of the penal field, and in consequence it produces a failure to deliver the kinds of analyses that are now urgently required to engage with political, policy and practice communities grappling with the challenges of delivering justice efficiently and effectively in fiscally straitened times – and with the challenges of communicating the meaning, nature, legitimacy and utility of supervisory sanctions to their publics (Bottoms, Rex and Robinson, 2004; McNeill, 2011).

Defining ‘offender supervision’: its aims and meanings

Some readers may already have noticed a certain slippage in terminology; we have referred sometimes to ‘offender supervision’, sometimes to ‘supervisory sanctions’ and sometimes to ‘community sanctions’. Whatever we call it, this is clearly a penal subfield around which it is difficult to draw precise boundaries, which is described and labelled differently in different places, and which has been characterised by the regular renaming that comes with innovation, differentiation and a perennial quest for credibility and legitimacy (Bottoms, Gelsthorpe and Rex, 2001; Robinson, McNeill and Maruna, 2013). In some cases, the changing terminology also reflects a shift in emphasis from welfarist rehabilitation towards more controlling and punitive forms of community punishment. Raynor’s (2007) preferred term, ‘community penalties’, reflects his jurisdictional home (England and Wales), and, as he acknowledges, it suffers from its failure to include the large populations subject to some form of supervision following release from custody or under pre-trial supervision. In other Anglophone jurisdictions (principally North America and Australasia) terms such as ‘community corrections’, ‘probation’ and ‘parole’ are used. Though these are broader in scope, they have the disadvantage of implying either a particular form of practice (correctionalist) or a particular form of legal order which is far from universal in its application, even in the jurisdictions in which such terms are used.

Given the avowedly European focus of this collection, we might have settled on the commendably neutral, if somewhat technical, label ‘community sanctions and measures’ (CSM), defined by the Council of Europe as:

What this definition lacks in depth, it makes up for in breadth: it succeeds in capturing not just the wide array of penalties handed down by courts (sometimes called ‘front-door’ measures) which fall between non-supervisory penalties (e.g. fines) and custodial sentences, but also statutory post-custodial (‘back-door’) measures associated with early-release schemes (such as parole). The use of the term ‘measures’ (as well as ‘sanctions’) allows attention to be paid to measures imposed pre-court and/or in lieu of prosecution, rather than restricting our attention to those that are imposed by judicial or quasi-judicial bodies.

Clear though it is, this definition is all form and no function. As Robinson, McNeill and Maruna note:

Putting this a different way, the term ‘community sanctions and measures’ refers to a kind of formal or legal scaffold, but it tells us very little about the kind of building whose construction it facilitates. It tells us little about the substance or the essence of offender supervision not just as a legal sanction or measure but as a socio-penal institution with its own distinctive (and, we suspect, highly variable) cultures and practices. It is partly for this reason that we have titled the book (and the research network which produced it) ‘Offender Supervision in Europe’. Though using that term runs the risk of colluding with the labelling and demeaning of (some) people as ‘offenders’, it is at least sociologically accurate: our interest is in institutions, cultures and practices of supervision that are directed at and to people precisely because they are labelled as offenders. So, for the record, let us make clear that we intend to label these institutions, cultures and practices and not the people who are their subjects.

Perhaps the initial question concerns how we ‘see’ (and often fail to see) offender supervision. As Hudson’s (2003) excellent introductory text on punishment both argues and demonstrates, there are many ways to construct and examine the objects of the penological gaze. Just as criminology is a ‘rendez-vous discipline’, so penology is a quintessentially interdisciplinary subject that compels and requires criminological, legal, philosophical and sociological scrutiny, as well as raising fundamental political and practical questions. We suggest that offender supervision needs to be scrutinised from all of these different vantage points.

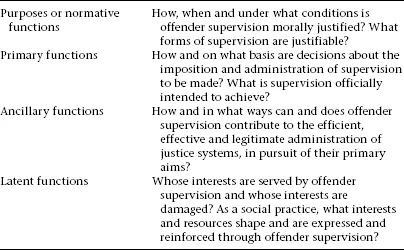

In similar vein, Tonry’s (2006) commanding and authoritative overview of the purposes and functions of sentencing also provides a neat framework for analysing penal sanctions. Tonry distinguishes between sentencing’s purposes or normative functions (i.e. its moral justifications), its primary functions (i.e. what it aims to achieve, such as the proper distribution of punishment; the prevention of crime; the communication of threat, censure and social norms), its ancillary or supporting functions (in contributing to the management of an efficient and effective justice system, and in securing legitimacy and public confidence) and its latent functions (the ways in which it reflects self-interest, ideology and partisanship, and how and what it communicates informally).4

The same taxonomy of perspectives, we suggest, can and should be applied to offender supervision; we can explore its purposes or normative functions, its primary functions, its ancillary functions and its latent functions, provoking respectively legal and philosophical enquiry, criminological research and analysis, and sociological interpretation. In Table 1, we suggest just a few of the questions that this taxonomy might raise about offender supervision.

Reviewing the (sub)field

The vast majority of the existing literature on offender supervision in Europe is descriptive or evaluative and confined to the analysis of supervision in single jurisdictions. Despite a small body of literature, largely inspired by Foucault’s seminal work Discipline and Punish (1975/77), which has centred on the ways in which supervision has adapted since the collapse of the ‘rehabilitative ideal’ in many western jurisdictions, and despite some ‘normative’ literature (especially in France and Germany) addressing the legal and constitutional requirements of forms of supervision, supervision remains relatively under-theorised as well as under-researched in comparative perspective.

Table 1 The purposes and functions of offender supervision

In recent years the most prominent strand of research in the field has addressed the ancillary functions of supervision and in particular its effectiveness. It is worth noting that there are at least two separate sets of questions here. One concerns the effectiveness of one type of sanction vis-à-vis another (usually prison sentences versus community sentences); the other concerns the effectiveness of particular styles of or approaches to supervision or intervention within the legal framework that the sanction requires.

The latter set of questions – about the effectiveness of particular methods and approaches – has been a particular preoccupation in Anglophone jurisdictions (for an excellent overview, see Raynor and Robinson, 2009), although it has also been the focus of much attention and development in the Nordic and the Low countries. Under the general banner of ‘What Works?’, much of this research has been sponsored by national governments (e.g. the Home Office in England and Wales) and is limited to the evaluation of programmes which, despite the amount of energy and investment directed at them, are accessed by only a small minority of offenders subject to supervision, even in those jurisdictions that are most committed to such programmes. At a recent CEP (European Probation Organisation) event concerned with sharing European experience around the accreditation of such programmes and co-sponsored by the Scottish Centre for Crime a...