This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

New Delhi: The Last Imperial City

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Johnson provides an historically rich examination of the intersection of early twentieth-century imperial culture, imperial politics, and imperial economics as reflected in the colonial built environment at New Delhi, a remarkably ambitious imperial capital built by the British between 1911 and 1931.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access New Delhi: The Last Imperial City by D. Johnson,Kenneth A. Loparo in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Asian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction: Seeing Like a (Colonial) State

The year 1911 was a momentous one for the British Raj in India. A new viceroy with tremendous foreign policy experience, diplomatic tact, and powerful intellect was bringing his skills to bear in his first full year in turbulent India. Lord Hardinge, Viceroy of India from 1910–1916, was the perfect high official to navigate the Government of India through India’s troubled waters. With his long experience as a diplomat in some of the era’s most difficult foreign policy arenas, such as Egypt, the Balkans, Eastern Europe, and Russia, he had learned to seek solutions that satisfied opposing viewpoints while maintaining his country’s primary requirements. His special skills were needed now more than ever in an India divided by anti-colonial agitation that threatened British security in the region. Problems had been exacerbated greatly by Lord Curzon’s 1905 partition of Bengal, which communally divided the province into a Hindu west and a Muslim east. Hardinge’s appointment as viceroy hinted that India’s disastrous colonial status quo would soon undergo modification, perhaps as early as the end of the year when a significant event would occur. George V, the new king-emperor, planned to travel to India for an extremely rare royal tour that would culminate in a grand imperial durbar, a royal assemblage, held in the ancient city of Delhi. Two previous durbars – Victoria’s in 1877 and Edward’s in 1903 – had been staged in the city because it was popularly recognized as one of India’s most important historical seats of empire. But George’s would surpass them both in size and pageantry.1 For the first time in the history of Britain’s Indian Empire, a reigning British monarch would personally receive homage from his Indian subjects and, perhaps more importantly in the existing political climate, bestow gifts on them in return for their loyalty.2

A special durbar committee was set up to plan the event and to make arrangements in the Delhi District – 25 sq. miles to the north of Delhi were set aside to house the 233 camps that contained nearly 200 ruling Indian princes and chiefs, representatives of British-Indian provincial governments, 70,000 to 80,000 British and Indian troops, special guests and sightseers. Infrastructure had to be built to handle the massive influx of people, which approximately doubled Delhi’s normal population of 250,000. Enough tents were raised to cover 10 sq. miles in canvas; 60 miles of new roads were built, 26.5 miles of broad gauge and 9 miles of narrow gauge railway were laid, 24 new railway stations were erected, and 50 miles of new water mains were set with 30 miles of pipeline for distribution in the camps. Markets, butchers, dairies, parks, gardens, and polo, football and review grounds were arranged. Enough electricity to light the towns of Brighton and Portsmouth was directed into the area. The actual durbar site and amphitheatre where the ceremony would take place had enough seating for 4,000 special guests, 70,000 people on a raised semi-circular mound, and space for 35,000 marshalled troops. The total cost for the durbar after the resale of tents and other reusable equipment was £660,000.

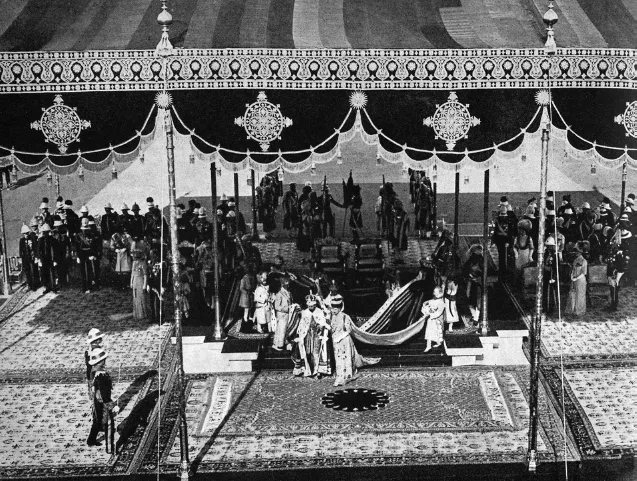

George V’s imperial durbar offered the perfect opportunity to reset colonial relations in India. Throughout 1911 and with strong support from George V, Hardinge, his executive council, and Lord Crewe, Secretary of State for India, crafted a broad new policy that offered colonial reforms and administrative changes to the Raj. Using the spectacle of a grand imperial durbar and George V as their voice piece, they introduced a new direction in colonial India that would have far-reaching consequences. Held in December of that year, the durbar ceremony (Figure 1.1) came off with only a few blemishes. A controversy surrounding the king’s crown,3 his less than spectacular state entrance into Delhi,4 and the Gaekwar of Baroda’s perceived insult to the royal couple5 were far outweighed by the king’s final proclamation. At the end of a long list of boons to his Indian subjects, George V offered his greatest gift of all. He declared that it was his royal wish to transfer the imperial capital from Calcutta to Delhi and, because of this great change, to reverse Lord Curzon’s 1905 partition of Bengal as recompense for that province’s loss of the imperial seat.6 According to Hardinge, the king’s announcement ‘came off like a bombshell … there was a deep silence of profound surprise, followed in a few seconds by a wild burst of cheering’.7 Due to the great secrecy surrounding the new scheme, few officials either in Britain or in India knew that the king, the Government of India, and the India Office were planning such a significant change in colonial policy in India.8

The grand announcement initiated a new colonial building project that would consume massive human, material and financial resources for the next two decades. It also generated a great deal of soul-searching and subsequent heated debate amongst colonial and elected officials and interested observers concerning the meaning and purpose of empire. For the building of the new capital was far more than a shift of where the Government of India did its business; it formalized and put an official stamp of approval on a decentralizing trend in the administrative structure of the British Raj where responsibility over certain government decisions was transferred from the central government to local provinces. As a response to specific historical conditions in India in the first decade of the twentieth century, the transfer of the capital from Calcutta to Delhi was designed to be ‘a bold stroke of statesmanship.’9

Figure 1.1 King George V (1865–1936) and Queen Mary (1867–1953) at the Delhi Durbar, India, 1911

New Delhi as a symbol of coercion and consent

The transfer of the capital and its related reforms represented the intersection of early twentieth-century imperial culture, imperial politics, and imperial economics as reflected in the colonial built environment at New Delhi, a remarkably ambitious imperial capital built by the British between 1911 and 1931. Hardinge, the man most responsible for transferring the capital, initiated a building project that came to represent a multifaceted vision of the late colonial state in South Asia where colonial reforms that were intended to give Indians greater political freedom simultaneously bound them more closely to the British Empire. As Indian resistance to British rule became greater in the twentieth century, older colonial methods of domination and control became increasingly less effective in dealing with Indian nationalists. British police officials could stop a demonstration with policemen armed with lathis (steel tipped canes), for example, but how could they stop Indians from making cloth at home as part of an anti-colonial boycott of British goods? This powerful form of colonial resistance pressured British officials to begin thinking of new ways to assert Britain’s colonial authority in India. India’s changed political conditions, exacerbated by previous colonial policies like Curzon’s partition of Bengal, demanded a new approach to an India which was undergoing tremendous political, social and economic transformations caused by its long interactions with Britain. The new capital symbolized Britain’s attempt to resolve the contradictory goals of giving Indians greater political power while at the same time strengthening Britain’s paramount power in India. As an important pivot of empire that constituted a significant percentage of Britain’s worldwide direct investment, India’s security had become essential to the economic health of Britain’s imperial world system, a fact not lost on those very Indian agitators who called for boycotts of British manufactured goods.

The transfer and building of a new capital at Delhi was an important response to the global challenges of a new geopolitical reality in which Britain was just one among many powerful industrial states, and not the best positioned one in regard to its supply of natural resources as the famous historian, John Robert Seeley, had noted in the early 1880s.10 Seeley claimed that states blessed with abundant natural resources such as the United States and Russia were destined to outpace Britain in the next century unless Britain changed its view of the empire and of itself. What was needed was a genuine and broad appreciation by the British people for the importance of empire, what it had done for Britain, and how it was central to Britain’s status as a world power. Britain needed a new imperial worldview, a ‘Greater Britain’ as he called it, based on communities of religion, race and economic interests shared by Britain, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. This new political, social and economic order, which combined the human and natural resources of Britain and its great dominions, would save Britain from slow decline in the face of foreign competition by more populated and resource-rich states. The role of India in this Greater Britain was always an uncomfortable fit for Seeley because it did not share with Britain a sizeable community of race or religion, but officials like Hardinge, Edwin Montagu, Undersecretary of State for India, and especially Fleetwood Wilson, Finance Minister to the Government of India, saw economic and political opportunities to better unify Britain and India.

The new capital’s grand neo-classical architecture and its rigid geometric town plan with multiple traffic circles and intersecting avenues has encouraged scholars to see the city as an expression of Britain’s attempt to control India by reimposing its coercive authority in the first decades of the twentieth century. Anthony King, for example, rigorously detailed New Delhi’s layout and the architectural styles employed by its two primary architects – Edwin Lutyens and Herbert Baker, two of the most gifted and celebrated architects of the era – who physically rendered the colonial social order and its world through the colonial built-environment.11 The power structure of colonialism and its culture determined the spatial and symbolic relationship of objects within the capital and of the capital itself to the existing Indian city of old Delhi, or Shahjahanabad as it was officially known.12 Robert Grant Irving also focused on Baker and Lutyens, arguing that the design of their city reflected Britain’s unification of an extremely diverse South Asian continent through the Raj’s material superiority.13 Metcalf’s intellectual history of British architecture in India, on the other hand, convincingly showed that New Delhi represented the culmination of a long history of experimentation in colonial architecture that ended with the building of New Delhi as a symbol of Britain’s power and permanence in India.14 Stephen Legg’s historical geography of the Delhi District showed how the physical built environment and its policing could be read as a colonial discourse that both represented and created relationships of power within and between new and old Delhi’s colonial landscapes.15 The studies above, in short, focus on New Delhi as a site of imperial coercion.

Yet there is a deep and important disconnect between what one sees in the built environment and what one reads in the archives. While this study certainly accepts the assertion that New Delhi was used to symbolize Britain’s power over India, it sees this as only half the story. Using Antonio Gramsci’s Marxist interpretation of hegemony, it argues that the new capital also was meant to encourage Indian consent to Britain’s colonial domination. Much as Gramsci argued that capitalist states use powerful forms of manipulation to encourage subjects to consent to their coercion, the Government of India offered political reforms to win Indian consent to continued British colonial rule.16 At this critical moment and as the pre-eminent symbol of British rule in India, New Delhi crucially displayed a double narrative of promised liberation and continued colonial dependence. Britain’s last imperial capital in South Asia was certainly a site of traditional imperial authority, but it was also a symbol of Britain’s willingness to address, and thus hopefully control, the political demands of its Indian subjects. As this study shows, the language of the most important colonial officials who crafted New Delhi’s new vision of empire reflected a willingness to engage educated Indians through political reforms. Even George V, as F. A. Eustis and Z. H. Zaidi long ago argued, desired a greater effort on the part of colonial officials to conciliate Indians.17 Metonymically and allegorically, the new capital may have projected imperial power and permanence, but it also symbolized the underlying strands that connected British political reform with the reinforcement and reaffirmation of continued British rule. If the new capital was meant to symbolize a new direction in British-India, it also was intended to show the absolute inseparability of the two peoples and their nations. This message, rich in ambiguity, created tension between a government intent on satisfying Indian demands for political reform with its equally important need to maintain its absolute authority.

Thus, in many important ways, New Delhi and its builders reflected the ‘high modernism’ that James C. Scott describes in Seeing Like a State. Though grounded in the Enlightenment’s celebration and elevation of natural law as the shaper of human destinies, Scott suggests that high modernism was more of a faith than a science. It was never the handmaiden of any one government or culture but, ‘as a faith’, according to Scott, ‘it was shared by many across a wide spectrum of political ideologies’.18

Like other high modernist cities, such as Brasilia, the building of New Delhi was a lesson in the state’s simplification of extremely complex socio-economic conditions in the Delhi District as well as what can only be called a gross vulgarization of the area’s history. The government’s massive acquisition of lands in the district for the new capital was one example of this simplification. The building project gave the local government freedom to transfer privately owned Indian lands...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Series Editors’ Preface

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction: Seeing Like a (Colonial) State

- 2 The Transfer of Britain’s Imperial Capital: ‘A Bold Stroke of Statesmanship’

- 3 New Delhi’s New Vision for a New Raj: An ‘Altar of Humanity’

- 4 Colonial Finance and the Building of New Delhi: The High Cost of Reform

- 5 Competing Visions of Empire in the Colonial Built Environment

- 6 Hardinge’s Imperial Delhi Committee and his Architectural Board: The Perfect Building Establishment for the Perfect Colonial Capital

- 7 ‘A New Jewel in an Old Setting’: The Cultural Politics of Colonial Space

- 8 Land Acquisition, Landlessness, and the Building of New Delhi

- 9 Conclusion: The Inauguration of New Delhi, 1931 – A British Empire for the Twentieth Century

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index