eBook - ePub

Emerging Issues in Contemporary African Economies

Structure, Policy, and Sustainability

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Onyeiwu focuses on how events of the twenty-first century are shaping key sectors of African economies and societies. He suggests that, compared to East Asia and Latin America, Africa still has a long way to go, despite recent improvements in performance.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Emerging Issues in Contemporary African Economies by S. Onyeiwu in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & International Business. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

How New Is the “New Africa”?

The media and commentators are abuzz with narratives about how Africa has finally turned a corner from years of lackluster economic performance. They seem to be fascinated by a “new Africa” that has been outperforming much of the rest of the world and threatening the economic hegemony of emerging markets. So impressive has the performance of the region been that financial market analysts have coined a new term for African countries: “frontier markets.” Twenty years ago, the focus of financial institutions and investors was on “emerging markets,” and Africa was discussed only in reference to military coups d’etat, humanitarian aid, wars, violence, and disease (especially HIV/AIDS). Africa has now become a focus of attention not only as a “frontier market,” but also as a region with new business opportunities, a bastion of natural resources, and a “hopeful continent.” According to Penny Pritzker, US commerce secretary, “The time to do business in Africa is no longer five years away. The time to do business is now.”1 Sentiments apart, are we really at a defining moment of African development, or is this yet another false start reminiscent of the 1960s? Is Africa about to take China’s coveted status as the economic powerhouse of the world? These are intriguing questions that cannot be answered without a systematic review of Africa’s recent economic performance.

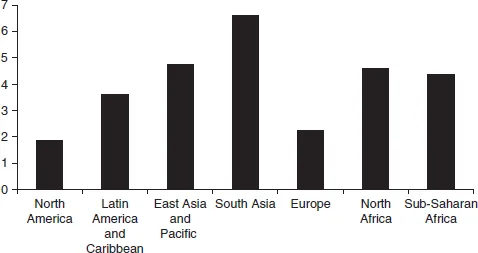

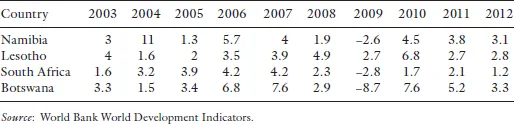

While much of the global economy has been grappling with anemic economic growth during the past decade, many African countries achieved impressive economic performance. Figure 1.1 shows that, aside from South Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), and North Africa achieved higher rates of growth of gross domestic product (GDP) than the rest of the world during 2003–2013.2

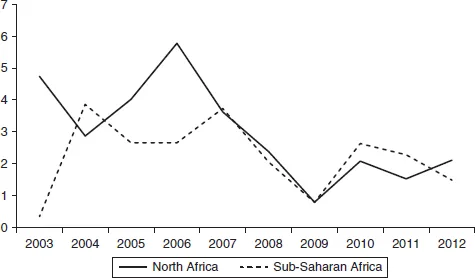

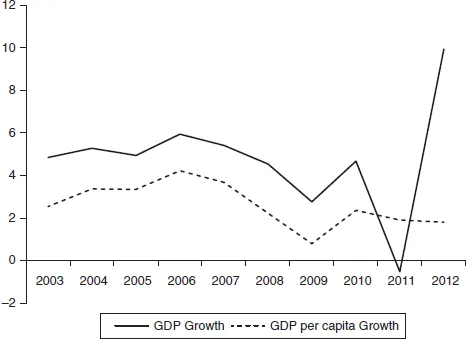

The region’s GDP grew by an average of 5 percent during 2008–2013, compared with a global average of 3 percent. About half of the 45 SSA countries achieved average growth rates of 5 percent and above during 2003–2013. The fastest-growing countries (i.e., those achieving growth rates of more than 7 percent) during 2003–2013 include Angola, Ethiopia, Chad, Sierra Leone, Equatorial Guinea, and Libya. Except for the period 2009–2011, North African countries grew faster, on average, than SSA countries (figure 1.2). This is despite the so-called Arab Awakenings, which not only disrupted North African economies, but also rattled tourists, foreign investors, and donors.3

Figure 1.1 Average growth rates of GDP (%), 2003–2013.

Source: Compiled from IMF World Economic Outlook Database.

Figure 1.2 GDP growth versus GDP per capita growth rates (%).

Source: World Bank World Development Indicators.

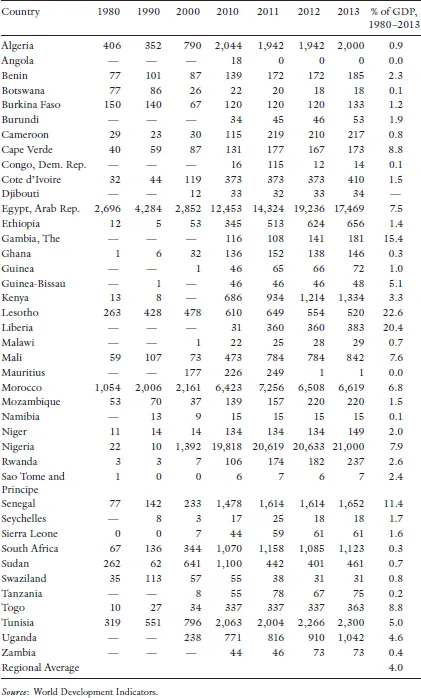

Growth in North Africa may have been buoyed by remittances and aid from the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states, which more than compensated for the loss in tourism revenue arising from instability in the region.4 As table 1.1 shows, worker remittances as a percentage of GDP in Egypt, Morocco, and Tunisia exceed the average levels in Africa. Remittances increased by an average of 84.92 percent in these three countries between 1980 and 2013.

Table 1.1 Migrant remittance inflows (in US$ million)

Figure 1.3 Africa GDP versus GDP per capita growth rates, 2003–2012.

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook and World Bank World Development Indicators.

Given population increases, GDP per capita grew at a much slower rate, averaging about 3.15 percent in North Africa and 2.04 percent in SSA during the 2003–2013 period (figure 1.3). However, this growth rate is still higher than the global average of 1.53 percent during the same period.

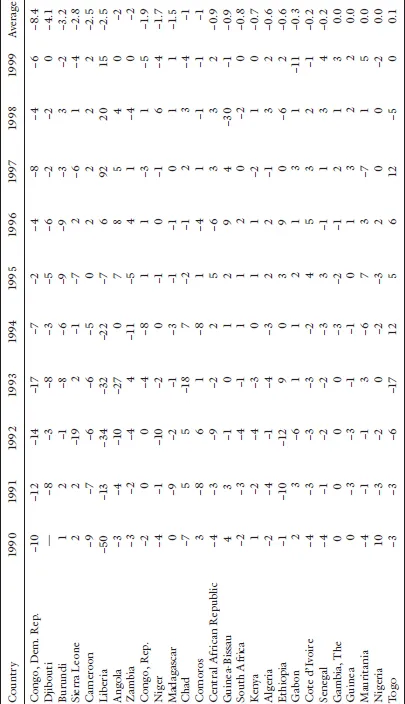

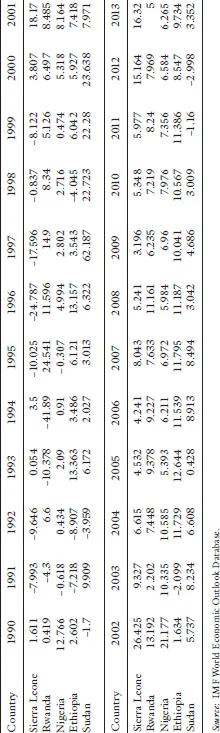

To gain a more incisive perspective on the performance of African countries, it is worth pointing out that, in the 1990s, several African countries achieved negative rates of growth of real GDP per capita (table 1.2).

During 1990–1999, 26 or about half of African countries had negative rates of growth of GDP per capita, but that number has decreased to only 6 countries between 2003 and 2013 (World Development Indicators Database).

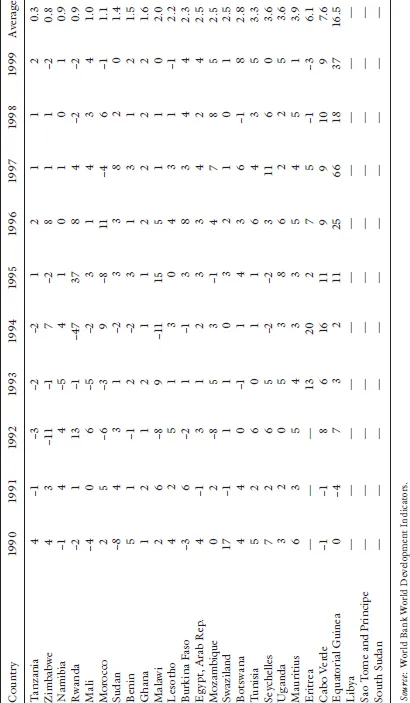

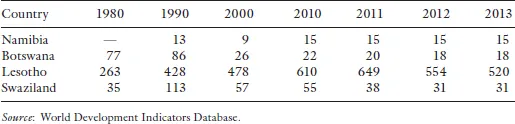

Intercountry variations in the growth of African economies are also reflected in the fact that countries that grew rapidly during the 1990s have witnessed slower growth rates in the past decade.5 In Senegal, growth has slowed down from an average of 5 percent during 1998–2005, to about 3 percent during 2006–2013, a decline attributable to lower levels of agricultural production, as well as difficulties in the manufacturing and extractive sectors.6 Botswana was applauded and showcased as one of the fastest-growing countries in the world in the 1990s, with an average rate of growth of GDP of 5.08 percent between 1990 and 2000, compared to 2.21 percent for SSA, 4.46 percent for North Africa and the Middle East, and 2.76 percent for the world, respectively. Botswana’s growth rate has averaged only 2.99 percent within the past 5 years, a contraction that is partly attributable to steep declines in diamond prices—the country’s main export. The prices of top-quality diamonds have fallen by about 80 percent in real, inflation-adjusted terms over the past 30 years (Arends, Undated). Other resource-rich countries whose economic growth rates have declined recently include Namibia, Lesotho, and South Africa, all heavily dependent on the export of diamonds (see table 1.3).

Table 1.2 GDP growth rates of African countries, 1990–1999

Table 1.3 GDP per capita growth rates (annual percent) of some resource-rich countries

Africa’s impressive growth performance has produced a number of “miracle countries” that were perceived as either too politically unstable, grossly mismanaged, or too resource-poor and landlocked to achieve any meaningful economic growth. The miracle countries include: Sierra Leone, Rwanda, Nigeria, Ethiopia, and Sudan. As table 1.4 shows, these countries achieved an average growth rate of GDP in excess of 7 percent during 2000–2010, compared to about 2.5 percent in the 1990s.

A number of useful lessons about growth in Africa can be learned from the experiences of the miracle countries:

An enabling macroeconomic environment is good for growth: The experiences of the miracle countries confirm the widely held notion that strong economic fundamentals are crucial for economic growth. A number of key macroindicators for the miracle countries show impressive trends over the past decade. For instance, general government net debt as a percentage of GDP has been declining in most of these countries. In Ethiopia, government debt as a percentage of GDP fell from 108.7 percent in 2002 to just 18.17 percent in 2012. In Sudan, gross debt as a percentage of GDP fell from 148.23 percent in 2002 to 90.94 percent in 2012. After years of excruciating debt burden, Nigeria reached a historic agreement with the Paris Club members of creditors that saw its gross debt as a percentage of GDP plummet from 68.78 percent in 2002 to 18.39 percent in 2012 (IMF World Economic Outlook Database). Other macroeconomic indicators have also improved, including inflation rate, which declined from 31.5 percent in 2002 to 2.4 percent in 2012, and budget deficits, which fell from 5.1 percent of GDP in 2002 to 2.4 percent in 2012.7

Resource scarcity is not a binding constraint on economic growth: While resource endowment can help shift a country’s production-possibilities frontier, enabling it to expand its consumption set, lack of natural resources is not intrinsically inimical to economic growth. Resource-poor countries such as Japan, South Korea, Singapore, Hong Kong (China), and Switzerland offer historical examples of how countries could grow with a paucity of natural resources. The impressive performance of resource-poor African countries such as Ethiopia, Mozambique,8 Rwanda, and Tanzania suggests that resource-endowment, while helpful, is not a precondition for growth. Some resource-rich countries (Botswana, Cameroon, South Africa, Namibia) are among the relatively slow-growing African countries during the past decade. Resource-poor African countries can promote economic growth through good governance, development of human capital, attraction of foreign investment, manufacturing, agricultural development, and tourism. Ethiopia’s agro-business sector, especially leather processing, has been instrumental in the country’s economic growth.

Table 1.4 GDP growth rates of “miracle countries”

To be landlocked is not necessarily a curse: Of the 54 countries in Africa, 16 are landlocked. Over half of the landlocked countries are resource-poor, a double whammy that would seem to be an insurmountable obstacle to sustained growth. Indeed, some analysts attribute the slow economic growth experienced by some African countries to their being landlocked (see, for instance, Collier and O’Connell, 2008). Landlocked countries face the following disadvantages: high transportation costs, risks associated with reliance on coastal countries for imports/exports, low trade volume, and fewer tourists. However, the case of some of the miracle countries (e.g., Ethiopia and Rwanda) suggests that being landlocked is not necessarily detrimental to growth. Uganda, another landlocked country, has posted impressive growth rates during the past decade. Landlocked countries may have advantages (such as good policies and governance, political stability, well-developed infrastructures, tourist attractions, etc.) that outweigh their lack of coastal access. Most of the landlocked countries in Africa (especially Botswana, Malawi, Namibia, Rwanda, and Zambia) have democratic or hybrid forms of government.

Growth does have spillover effects: The porosity of African borders, while posing risks to security along with many other challenges, can also generate positive externalities for neighboring countries.9 Porous borders have enabled poor residents in Benin Republic and Niger to cross over to Nigeria in search of better economic conditions. These migrants often end up as house helps, service-sector employees, street hawkers, and beggars. Nigerians have also migrated to Ghana in search of opportunities in the informal sector. Border crossings and movement of goods have had positive impacts on growth in countries that are proximate to fast-growing countries. Most of the countries bordering the miracle countries have had growth rates that exceed their expected thresholds, considering their size, resource endowments, and previous growth paths. Benin Republic and Togo, two countries located between Ghana and Nigeria, have benefited from the latter countries’ growth. Growth in Rwanda has also spilled over into Uganda. When two contiguous countries like Rwanda and Uganda grow fast, their proximity becomes synergistic, generating even higher growth rates than would normally be the case.

Though Niger’s growth is partly attributable to the recent discovery of oil in that country, it has benefited from growth in Chad, Libya, and Nigeria. Conversely, slow economic growth, war, and violence in one country could negatively impact neighboring countries as well. Concerned about the negative effects from the violence and instability in neighboring Central African Republic (CAR), the Republic of Chad closed its borders with that country on May 12, 2014, vowing to reopen them only when normalcy returns.

Table 1.5 Worker remittances in selected Southern African countries (US$ millions)

The recent slowdown in the growth of the South African economy appears to have spilled into neighboring countries like Namibia, Lesotho, Swaziland, and Botswana. There are two main transmission mechanisms that make growth in South Africa contagious for neighboring countries. First, manufacturers and exporters in these countries rely heavily on the South African market. There is a very strong trade relationship between South Africa and its neighbors. In 2012, exports to South Africa constituted approximately 13 percent of Botswana’s total exports, while imports from South Africa made up 62.8 percent of Botswana’s total imports. For Namibia, exports to South Africa accounted for 17.4 percent of Namibia’s total exports and imports from South Africa made up 69.7 percent of total imports.10 The second mechanism is through worker remittances from South Africa, which accounted for about 12 percent of Lesotho’s GDP in 2013. In the 1990s–2000s, the South African economy provided succor to thousands of Zimbabweans fleeing economic difficulties back home. Partly due to slow growth in South Africa, remittances to neighboring countries like Namibia, Botswana, Swaziland, and Lesotho have been declining since 2010 (see table 1.5).

Explaining Africa’s Growth Performance

Every analyst has his or her favorite factor or factors that are driving growth in Africa. However, explaining economic growth in Africa can be a daunting task. Given the interplay of various factors in the region’s growth, monocausal explanations are unhelpful in understanding the current growth spurts in Africa. While economists agree there are some basic factors (such as investment in physical and human capital, discovery of new resources, tra...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Chapter 1 How New Is the “New Africa”?

- Chapter 2 Renaissance or Mirage: Can Growth in Africa Be Sustained?

- Chapter 3 Growth, Employment, and Poverty

- Chapter 4 Industrial Performance and Prospects of Structural Transformation

- Chapter 5 Regionalism and Industrial Development

- Chapter 6 Innovation, Technology, and Structural Transformation

- Chapter 7 Information and Communication Technologies

- Chapter 8 Aid, Debt, and Foreign Direct Investment

- Chapter 9 Gender, Youths, and Sustainable Development

- Chapter 10 Closing the Development Gap in Africa

- Notes

- References

- Index