eBook - ePub

Maritime Piracy and Its Control: An Economic Analysis

An Economic Analysis

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Maritime Piracy and its Control develops an economic approach to the problem of modern-day maritime piracy with the goal of assessing the effectiveness of remedies aimed at reducing the incidence of piracy.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Maritime Piracy and Its Control: An Economic Analysis by C. Hallwood,T. Miceli in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Economic Policy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Scope of the Problem: History, Trends, and Current Facts

Abstract: Chapter 1 reviews the nature of modern-day maritime piracy by offering data on the incidence and type of attacks in recent years. It also offers estimates of the cost of piracy, which ranges between $1 billion and $16 billion per year. Finally, the chapter previews the content of the remaining chapters in the book.

Hallwood, C. Paul, and Thomas J. Miceli. Maritime Piracy and Its Control: An Economic Analysis. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015. DOI: 10.1057/9781137461506.0006.

The goal of this monograph is to develop an economic perspective on the interaction of maritime pirates and international enforcement agencies for the purpose of assessing the effectiveness of international law and of examining potential revisions of the law, with the aim of reducing the incidence of piracy. Specifically, we examine the question of why international cooperation has proven to be largely ineffectual. For example, Kontorovich and Art (2009) found that over the period 1998–2009 less than 2% of acts of maritime piracy were prosecuted, while Shortland and Vothknecht (2011) found that naval patrolling in the Gulf of Aden (beginning in 2008) might only have stabilized the level of piracy at a high level and may also have caused it to shift to more lightly patrolled areas. Although more recently there has been a drop in the incidence of piracy, we think that is at least partly due to the increasing use of onboard armed guards by merchant vessels.

Various arguments have been put forward to explain the general failure of enforcement by government agents. The UN Secretary General has pointed to gaps in domestic laws and the reluctance of countries to bear the expense of imprisoning pirates (UN, 2010, p. 10). Mo (2002) argues that it is due to a lack of cooperation among naval powers, while Campanelli (2012) attributes it to a lack of a global enforcement authority, implicitly acknowledging failure in international cooperation that such an authority might promote. In contrast, Bulkeley (2003) and Farley and Gortzak (2009) point to some success in multilateral cooperation in Southeast Asian waters, with the latter highlighting the important role of US leadership there.

On the question of international law governing maritime piracy, Andersen, Brockman-Hawe, and Goff (2010) and Ivanovich (2011) emphasize the absence of an effective governing legal framework. Indeed, the lack of such a framework bedevils international public law as a whole, not just in the area of policing and enforcement against maritime piracy. As Goldsmith and Posner (1999) and Brunnee and Troope (2011) argue, whether a country agrees to abide by international treaty law is voluntary in the sense that no country is obligated to sign a treaty, and clauses can always be written in such a way that they allow countries to sign the treaty while leaving them with minimal or undefined obligations. For example, under the Law of the Sea (LOS), signatories agree to ‘cooperate,’ but as the term is not defined, there are no sanctions for failing to cooperate.1 In Chapter 9 we will delve more deeply into this ‘mystery of international public law.’

Previous theoretical literature on piracy has taken one of two routes. One strand focuses on the organization and governance of pirates in a modern context (Bahadur, 2011), as well as in a historical context (Leeson, 2007a). The other examines the economic gains from piracy. For example, Anderson and Marcouiller (2005) analyze piracy in a two-country Ricardian model of trade, while Guha and Guha (2011) examine self-insurance by merchants and third-party enforcement as complementary approaches to the control of piracy. They show that increased enforcement does not necessarily involve moral hazard in the sense that it may not cause merchants to decrease the amount of self-insurance that they invest in.

Our investigation is based on a standard Becker-type model of law enforcement (Becker, 1968; Polinsky and Shavell, 2000), which we extend to consider the effort level of pirates to locate and attack target vessels and of shippers to invest in precautions to avoid contact. We then use the model to evaluate the feasibility of the resulting optimal enforcement policy within the context of international law and conclude by proposing some changes that might improve matters. We set the stage for the analysis by briefly reviewing the state of modern-day piracy.

1.1Overview of piracy in recent times

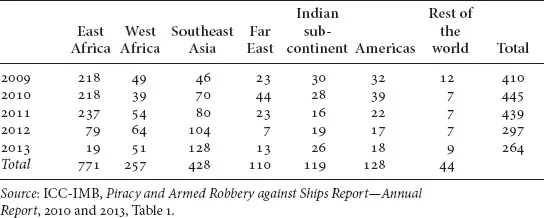

The International Maritime Bureau (IMB) records details of pirate and armed robbery attacks on shipping around the world. Table 1.1 shows the number and location of ships attacked during the period 2009–2013. East Africa, especially off Somalia in the Indian Ocean and in the Gulf of Aden, suffered the most attacks. Southeast Asia also had many incidents, with several other areas being affected as well. The number of attacks in this period peaked in 2010, then fell by 40% by 2013, and the decline has continued through 2014.

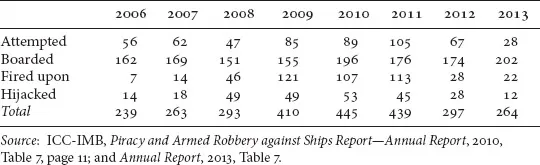

Table 1.2 shows the type of attack. Boardings led to hijacking or robberies, though in some instances pirates left empty handed. Table 1.3 records the type and number of personal violations suffered by crews of boarded ships. Notable is the initially rising trend, from 317 violations of the person in 2006 to a peak of 1,270 in 2010, but a decline thereafter to 373 in 2013. The largest component of violations is hostage taking, with the Gulf of Aden and the Western Indian Ocean accounting for the bulk of incidents in the peak year of 2010 (998 of the 1,181).

TABLE 1.1 Total incidents of piracy and armed robbery by region

TABLE 1.2 Types of piracy and armed robbery attacks and violence, 2006–2013

TABLE 1.3 Types of violence against seafarers

1.2Piracy versus armed robbery

The data in Tables 1.1–1.3 do not distinguish between incidents of piracy and of armed robbery. Armed robbery occurs within a state’s territorial waters where international piracy law, as expressed in Articles 100–107 of the LOS, technically does not apply. International piracy law applies only outside the territorial waters—on the high seas and in the Exclusive Economic Zones. A better idea of the incidence of piracy (as opposed to armed robbery) is gained by subtracting out attacks, actual and attempted, on ships either anchored or berthed, as these are most likely to be within a state’s territorial waters.

Measured this way, in 2013 there were 197 attacks on ships in territorial waters. Given that the total number of attacks (including attempted) that year was 264, there was a total of 67 attacks where the jurisdiction of the LOS applies, or 25% of the total. By area, this breaks down to 29 off West Africa, 15 off East Africa, 14 off Southeast Asia, 5 off the Far East, 3 off the Americas, and 1 off the Indian sub-continent. Given that the total number of attacks (successful and attempted) came to about 2,650 over the eight-year period of 2006–2013, and applying the 25% figure, this means that there were about 660 incidents that came under LOS jurisdiction.

Examination of IMB narrations of piracy attacks indicates that Somali piracy is aimed at taking ships and their crew hostage, primarily for ransom. For example, in February 2011, 31 vessels and 700 people were held hostage as part of a ‘capture-to-ransom’ business model. Although modern-day Somali pirates have claimed that they are not motivated by private gain, but are instead acting in the interests of Somalia, our investigation of this claim in Chapter 3 suggests that such a claim is unlikely. The motive of private gain predominates. Moreover, as far as we know, it has never been challenged that in other parts of the world pirates are motivated by self-interest, primarily through robbery.

1.3The cost of piracy

The annual cost of piracy off Somalia to the maritime industry is estimated to lie between $1 billion and $16 billion. These costs are attributable to the addition of 20 days per trip for ships re-routing via the Cape of Good Hope; increased insurance costs of as much as $20,000 per trip, owing to the designation by insurance agents at Lloyd’s of London of the Gulf of Aden as a ‘war risk zone’; increased charter rates, as longer time at sea reduces the availability of tankers; and greater inventory financing costs for cargoes staying longer at sea (Madsen et al., 2014; Bowden, 2010; O’Connell and Descovich, 2010; Wright, 2008). Moreover, the owners of ships taken hostage usually pay ransoms of between $500,000 and $5.5 million, sometimes more. Another cost of maritime piracy is its adverse effect on the volume of international trade. According to Bensassi and Martínez-Zarzoso (2012), an additional 10 hijackings are associated with an 11% decrease in exports between Asia and Europe, at an estimated cost of $28 billion.

As to anti-piracy efforts, Anderson (1995) recognizes economies of scale in this activity. When trade on a given shipping route is sparse, individual merchant ships have to arm themselves, thereby duplicating investment. With greater amounts of trade, however, several shipping companies may reduce costs by hiring armed ships for their protection as they sail in convoy. And with still greater shipping traffic, the least cost protection method has turned out to be patrolling of large areas of ocean space by warships.

The international community has engaged in some cooperation to combat piracy, with several naval task forces operating off the Horn of Africa. The European Union has Operation Atalanta with about 20 warships and 1,800 personnel—in 2012 this operation was extended for another two years. Combined Task Force 151 in the Horn of Africa area is led by a US admiral, but its naval forces are drawn from 30 volunteer countries on a rotating basis, and no country has to participate in activities it does not want to.2 NATO has Operation Ocean Shield (replacing the earlier Operation Allied Protector) to escort humanitarian relief supplies to the Somali coast. Several individual countries also have warships in the area, including China, India, Saudi Arabia, and South Korea. The EU also operates a voluntary information exchange, whereby merchant and other ships transiting the area can coordinate with EU naval forces. The International Maritime Organization also collects and broadcasts information on piracy incidents. The annual cost of these navies is estimated by Bellish (2013) to be about $1.15 billion.

However, as Liss (2007) observes, even with naval patrolling, merchant shipping can still find it advantageous to employ private military companies, or to otherwise arm themselves, something that they have increasingly done in the past few years. This ‘self-protection‘ strategy is often the best means of deterrence in the light of the failures of general enforcement by national governments.

1.4Organization of the book

The book proceeds in the following way. In Chapter 2, we examine pirate organization with reference to what it was like in the age of sail and what it is like today. Apart from the intrinsic interest, our main aim here is to relate pirate efficiency to its impact on merchant shipping. The more efficient is the machinery of piracy, the greater will be its adverse impact on shipping, and consequently, the greater must be countering expenditures on naval patrols and onboard armed security guards.

As the motivations of Somali pirates have been questioned, Chapter 3 uses an economic model to try to uncover what the real motivation is. The choice is between ‘protecting the interests of Somalia,’ as some pirates and academics have claimed and ‘for private gain’—which is the basic assumption used in the law and economics literature on crime, as exemplified by Becker (1968). We use a technique developed by Hallwood (2013) to investigate this question, and, based on some simple calculations, we argue that the ‘for private gain’ motive most likely predominates.

In the two chapters that follow after that we present our economic model of ‘the piracy problem.’ In Chapter 4 we model both pirates and shippers as rational maximizers and uncover the resulting complex interactions. Using this approach, we come to understand why shippers may choose to change shipping routes, to increase speeds, or to employ armed onboard guards—in short, to self-protect. A curious finding is that the frequency of pirate attacks may increase even as naval patrolling increases. This could occur if, feeling safer, more shippers were induced to use a given shipping route, thereby increasing the opportunities for attack. ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 The Scope of the Problem: History, Trends, and Current Facts

- 2 Pirate Organization: Yesterday and Today

- 3 Somali Piracy: For the Money or for the Honor?

- 4 An Economic Model of Maritime Piracy: Part 1, Pirates and Shippers

- 5 An Economic Model of Maritime Piracy: Part 2, Optimal Enforcement of Anti-piracy Laws

- 6 Reform Proposals: Part 1, Apply the SUA Convention to Piracy

- 7 Reform Proposals: Part 2, Apply Civil Aviation Laws to Piracy and Use the International Criminal Court to Try Pirates

- 8 Piracy in the Golden Age, 1690–1730: Lessons for Today

- 9 Conclusion: The Mystery of International Legal Obligation

- References

- Index