This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Exploring the way in which criminal punishment is interpreted and narrated by offenders, this book examines the meaning offenders ascribe to their sentence and the consequences of this for future desistance.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Being Imprisoned by M. Schinkel in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Criminology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

Introduction

Criminal punishment represents the state’s most serious intrusion upon the human rights of its citizens. However, beyond (ex-)offender autobiographies, there is remarkably little in-depth empirical evidence about how those who are punished interpret their sentence. This book starts to address this gap in our knowledge – based on narrative interviews with 27 (ex-)prisoners in Scotland, it explores how these men saw their sentence, its impact and their future.

There is an increasing criminological literature on the criminal careers of offenders, including how they come to desist from crime (Giordano, Cernkovich and Rudolph, 2002; Maruna, 2001; Sampson and Laub, 2003) and a well-developed body of work on the lived experience of the conditions of imprisonment (Carrabine, 2004; Crewe, 2009; Liebling, 2004; Sparks, Bottoms and Hay, 1996; Sykes, 1958). Some of this work has touched on the ways in which punishment is given meaning. For example, Crewe (2009) found that only a limited number of prisoners opposed their sentence and both Sampson and Laub (2003) and Giordano et al. (2002) noted that some people saw their prison sentence as a turning point in their lives. However, so far the question of how criminal punishment is interpreted has received little detailed attention (Rex, 2005). Moreover, criminological research has provided limited knowledge of which aspects of imprisonment (if any) help people to deal with problems both before and after release. Yet, long-term imprisonment is the most serious sentence available in most Western jurisdictions, and a very costly one at that, with the annual average cost per prisoner in Scotland being £32,146 (Scottish Prison Service, 2012). If the process by which imprisonment is given meaning and is evaluated in terms of fairness has the power to contribute in any way to desistance and reintegration (positively or negatively), then it is imperative that we know more about this process and the factors that influence it.

This book examines the narratives of long-term prisoners, with a special focus on the meaning they ascribe to their sentence, and the consequences of this for their future offending. As the title suggests, it is about how prisoners make sense of ‘being imprisoned’, and the personal and practical consequences of this process of meaning-making for their present and future lives. The book thereby aims to bring together strands of literature that have so far remained mostly separate: the literature on prison life and the moral performance of prisons; the literature on desistance; and the more theoretical literature on the purposes and legitimacy of criminal punishment.

With this in mind, the purpose of this book is two-fold. First of all, it aims to give a fine-grained account of the way in which long-term prisoners give meaning to their sentence. This is intended to start addressing the gap in the literature about how sentences are experienced as a sanction by those who undergo them. As noted above, there is a well-developed literature on the experience of imprisonment, but this tends to focus on matters internal to the prison, thereby failing to connect this experience to issues of justice and the lives within which prisoners give their sentence meaning. By providing a more contextual account it becomes possible to connect in-prison experiences with pre- and (projected) post-prison biographies, leading to a deeper understanding of the impact of sentences and the way in which their meaning is dependent on what has come before and follows after.

Furthermore, a more in-depth and contextual account of the experience of imprisonment allows for an exploration of how it connects (or fails to do so) with processes of desistance. So far, most studies of desistance have focused on studying desistance per se, examining the processes that help people to desist (for example Maruna, 2001). In doing so, some studies have found that criminal punishment, and especially imprisonment, can be experienced as helpful in moving away from crime (for example Aresti, 2010; Giordano et al., 2002). On the other hand, the criminogenic effects of imprisonment have been well documented (Liebling and Maruna, 2005). With increasing pressure (and with the aspiration in many jurisdictions) to make sentences effective, and with imprisonment as the punishment of choice for the most serious and troublesome offenders, an examination of how imprisonment and desistance interact is essential. The extent to which a sentence facilitates desistance will depend on how it is perceived and given meaning. At the most basic level, if the punishment is experienced as unjust, this is more likely to lead to a negative view of the authorities, reduced motivation to abide by the rules (Franke, Bierie and Mackenzie, 2010; Robinson and McNeill, 2008) and ultimately, to future offending (Sherman, 1993), rather than to desistance. More specifically, Maruna (2001) has pointed out that the pressure to take responsibility for the crime committed that is exerted in most sentences may be counterproductive for the subjective meaning-making processes that support desistance, including seeing oneself as essentially good. How a sentence fits in with one’s wider life is likely to have an impact on desistance: how much one loses through imprisonment (in terms of housing, jobs, relationships, but also self-respect), and what resources are still in place to counteract these deprivations, will influence whether desistance is more or less likely after imprisonment.

The second purpose of the book is to provide an empirical examination of the most commonly used justifications of punishment. Because criminal punishment in general, and (long-term) imprisonment in particular (Carrabine, 2004; Mathiesen, 1965; Sparks et al., 1996; Sykes, 1958) is a serious intrusion by the state into private lives, it is important to examine whether it achieves its stated aims. Only by examining lived experience is it possible to see whether the justifications given for punishment fit the ways it plays out in the lives and minds of the punished. Usually states, their institutions and employees use a mix of rationales when justifying punishment. On the one hand, they tend to justify punishment through its positive effect of reducing crime (and in current idiom thereby ‘protecting the public’). Deterrence, rehabilitation, reform and incapacitation are all often cited as the aims (and justifications) of punishment. On the other hand, they also justify criminal justice practice in more retributive terms, relying on the idea that there is an intrinsic link between crime and punishment, and that the sentence is the offender’s ‘just deserts’. For example, the most recent Scottish specification of the purpose of sentences was given in the Criminal Justice and Licensing (Scotland) Bill of 2010. It stated that sentences should aim to achieve:

the punishment of offenders, the reduction of crime (including its reduction by deterrence), the reform and rehabilitation of offenders, the protection of the public, and the making of reparation by offenders to persons affected by their offences. (Section 1.1)

As is common in many jurisdictions, the Bill expresses mixed purposes for sentencing related to crime reduction (deterrence, reform and rehabilitation) and retributive punishment.

Few of these purposes of sentencing can be seen as achieved if they are not reflected in the experiences of the punished. Deterrence depends on people being aware of the threat of punishments, finding these punishments sufficiently aversive and thinking they are likely enough to get caught to refrain from offending (in the future). Reform and rehabilitation require that people think, or at least act, differently than before in relation to offending. The retributive insistency on ‘just deserts’ makes the experiences of the punished relevant to punitive purposes as well. Because offences have to be punished proportionally (the more serious crimes should be punished more severely) it is necessary to know how much suffering each punishment imposes. In reality, the assumption is made that the ‘same’ punishment, say four years in prison, affects everyone in the same way, but some have argued that an effort should be made to anticipate the actual experience of suffering for each individual (Curran, MacQueen and Whyte, 2007; Kolber, 2009). Their reliance on suffering also means that retributive justifications depend on the adverse experience of punishment in a more fundamental way: if offenders actually experience their sentence as preferable to their usual life, then it does not fulfil its punitive function. Among the most commonly used justifications of punishment, only incapacitation could be said to work independently of people’s internal worlds, because it controls their external one, although research by Wood et al. (2010) suggests that even this is only partially true.

With justifications of punishment generally focusing on the sentence itself, it is also important to examine whether the borders of the punishment lie where intended. Many believe that the only punishing aspect of imprisonment should be that it takes away prisoners’ liberty (see for example Liebling, 2004, p. 305). However, it is well known that imprisonment has additional adverse consequences for many prisoners, in their personal and working lives, and long after they have been released. The stigma of imprisonment makes it more difficult to find employment (Pager, 2003; Schneider and McKim, 2003; Social Exclusion Unit, 2002). Imprisonment can have long-term negative health consequences (Massoglia, 2008; Schnittker and John, 2007) and released prisoners are at much higher risk of dying during their first two weeks of freedom, notably because the risk of a drug overdose is high (Binswanger et al., 2007; Bird and Hutchinson, 2003). Being imprisoned makes divorce more likely (Apel, Blokland, Nieuwbeerta and van Schellen, 2010) and has further negative consequences for the partners and children of prisoners, such as stigma, mental health problems, financial strain, (future) unemployment and an increased likelihood of drug use or involvement in criminal activity (Murray and Farrington, 2008; Murray, 2005, 2007). All in all, imprisonment places a burden on the prisoner (and his or her family) that extends far beyond (the period of) loss of liberty (Ewald and Uggen, 2012; Liebling and Maruna, 2005; Petersilia, 2000). This book therefore also examines what exactly long-term imprisonment encompasses in the eyes of those who experience it, and how this affects the sentence’s legitimacy in their eyes.

Studying the meaning of imprisonment

The research that forms the basis for this book focused on the experiences of long-term prisoners, not explicitly excluding or including those given a life sentence. This population was chosen as being of special interest, because long-term prison sentences are the most intrusive sentence in their impact, taking away freedom and normality for a significant portion of a person’s life. Long-term prisoners were also anticipated to be more likely than short-term prisoners to have reflected on their sentence and to have experience of a wider variety of aspects of sentencing. For example, whereas short-term imprisonment has relatively recently been described as mere warehousing (Scottish Prisons Commission, 2008), long-term prisoners in many jurisdictions usually have the opportunity to engage in work, education and programmes related to their offending. They also often receive some form of statutory post-release supervision and support once released on licence, which means that they will meet regularly with a probation or parole officer or (in Scotland) a criminal justice social worker in the community. Men and women were anticipated to make sense of their sentences in different ways, considering that among female prisoners substance abuse and mental health issues are even more prevalent than among male prisoners, and that they are more likely to be the main caregiver for their children (Commission on Women Offenders, 2012; HM Inspectorate of Prisons, 2010). With adult male offenders the most numerous and with obtaining access to multiple prisons problematic, it was decided to focus on this group. To explore the issues outlined in the rationale above, the following research questions were formulated:

•What meanings do prisoners give to their sentences? Do any of these meanings align with normative theories? How are these meanings ascribed?

•Do prisoners’ accounts indicate that any of the stated aims of punishment are achieved?

•What unintended meanings and consequences do long-term prison sentences have?

•Do prisoners see their sentences as justified? Why (not)? What are the implications of this?

•Does the way prisoners see their sentence change as they progress through their sentence?

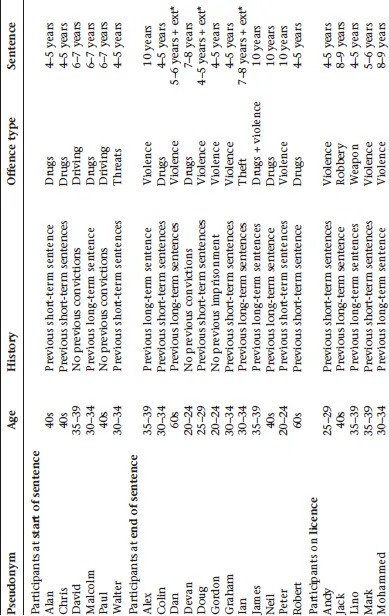

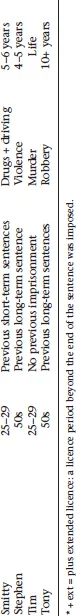

These questions were explored in twenty-seven interviews with three groups of long-term adult male prisoners: men at the start of their sentence, men at the end of their sentence and men on licence. This cross-sectional design was chosen to answer the question of how meanings change over time. A longitudinal design would have been ideal, with the same prisoners interviewed repeatedly, but given the time limits on the duration of the study and the length of the sentences imposed, this was impossible. Table 1.1 gives some basic information about each of the men, along with the pseudonyms they chose, which will be used in the remainder of this book. More in-depth information about their circumstances is contained in Appendix I, where the narratives that this book draws on most heavily are summarised.

The interviews were conducted in 2009 and 2010 in two prisons and two criminal justice social work offices in Scotland. Most interviews lasted between one and one and a half hours, with the shortest interview 39 minutes and the longest two hours and 20 minutes. Because the meanings of sentences ascribed by the punished have been studied so little, there was a strong possibility that the research questions would not capture all that was relevant. For this reason, and to answer the question of how meanings are ascribed in the context of people’s lives, a narrative methodology was decided upon (see Appendix II for more details). As Polkinghorne writes:

The storied descriptions people give about the meaning they attribute to life events is ... the best evidence available to researchers about the realm of people’s experience. (2007, p. 479)

While the interviews were mainly narrative, and explored the way the men interpreted their sentence and incorporated it in their wider life story, if they did not touch on questions of legitimacy and purpose spontaneously they were asked semi-structured questions about these issues at the end of the interview.

Table 1.1 Participants’ characteristics

In transcribing the interviews, the following notation, adapted from Banister et al. (1994) was used:

| (.) | pause | |

| (xxxx) | unintelligible speech | |

| (judge) | doubtful transcription (best guess) | |

| [laughs] | non-verbal utterances | |

| [town] | substituting generic labels for specific names, to safeguard anonymity | |

| / | overlapping speech or aborted statements | |

| UPPER CASE | emphasis in speech |

In addition, in the quotes in this book, occasionally ... is used to indicate where some speech or text has been omitted.

In this book, the accounts of the men at the end of their sentence and on licence are discussed in most depth, and are explicitly compared in Chapter 4 and 5. The men at the start of their sentence are not considered as a separate group. Chris, Malcol...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Meanings and Experiences of Punishment

- 3 Purposes Perceived in the Sentence

- 4 Legitimacy and the Impact of the Prison Environment

- 5 Narrative Demands and Desistance

- 6 Conclusion

- Appendix I: Narrative Vignettes

- Appendix II: Narrative Methods

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index