eBook - ePub

Digital Online Culture, Identity, and Schooling in the Twenty-First Century

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Digital Online Culture, Identity, and Schooling in the Twenty-First Century

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Digital Online Culture, Identity and Schooling in the Twenty-First Century provides a cultural, ideological critique of identity construction in the context of virtualization. Kimberly Rosenfeld explores the growing number of people who no longer reside in one physical reality but live, work, and play in multiple realities. Rosenfeld's critique of neo-liberal practices in the digital environment brings to light the on-going hegemonic and counter-hegemonic battles over control of education in the digital age. Rosenfeld draws conclusions for empowering the population through schooling, and how it should understand, respond to, and help individuals live out the information revolution.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Digital Online Culture, Identity, and Schooling in the Twenty-First Century by K. Rosenfeld in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Media Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Virtualization and Digital Online Culture

Contemporary citizens live in complicated times where fundamental understandings of reality are being expanded and challenged. A growing number of people no longer reside in just one physical reality but live, play, and work in multiple realities: real life reality, simulated reality, augmented reality, virtual reality, and hyperreality. As each crosses over from specialized functions (i.e., military training and scientific research) into everyday use, it impacts modern ontological states. Multiple realities are so pervasive that we see them across different contexts, such as at our local mall in the form of advertisements, on our smartphones in the form of applications, and at home in our appliances.

This book maps some of the sociological and psychological changes to our lives as a result of computer technology. This work’s aim is to initiate a conversation about how schooling should understand, respond to, and help individuals live out the information revolution. To achieve these goals, I will deconstruct two distinctions fundamental to my writing during a time when each reality’s delineation is dwindling. The first distinction is between real life (RL) and virtual life (VL) and the second is between humans and machines.

Within the context of this book, computer technology includes artificial intelligence, human–machine hybrids, computer devices, and various stages of simulation. When I reference technology, I also mean the material and immaterial aspects of both virtualization and digital online culture that play an active role in constructing users’ identities. This includes the physical objects that serve as portals to virtualization such as smartphones, the software that runs them, and the software that runs on them in the form of applications and games. The immaterial refers to the social and culture practices around the use of these objects, including but not limited to changes to our social norms around language, disclosure, privacy, access to and use of information, social networking, and activism.

It is also important to keep in mind that technology is not all good or all bad, so as this topic is explored, I make an effort to consider the positive as well as the negative. Thus, along with the magical utopia of freedom, democracy, and unfettered learning the virtual represents, there is ideology and materiality to it that is not always so idealistic. There is physicality to the virtual that relies on the actual bandwidth, pipelines, wires, towers, servers, and the myriad sophisticated objects with their unique affordances. A human factor accompanies the physicality in the form of social class, race, gender, and hegemony that accompany the armada of service providers, designers, creators, and marketers who are tangible parts of this fantastic world and are often implicit actors in our virtual experiences. Both sides to this materiality are fueled by a neoliberal undercurrent that is implicated in many of the ideological battles playing out in both RL and VL.

I use neoliberalism here in reference to political and economic practices that uphold the doctrine that the best way to advance human well-being is to allow unfettered individual entrepreneurial freedom through competition in a self-regulated market (Harvey, 2007). As Ken Saltman notes, “In the view of neoliberalism, public control over public resources should be shifted out of the hands of the necessarily bureaucratic state and into the hands of the necessarily efficient private sector” (2010, p. 23). This is achieved largely through open markets, free trade, privatization, deregulation, and a state at the service of the private sector (Harvey, 2007; Lee & McBride, 2007; Torres, 2009). As Saltman continues to argue, “By reducing the politics of education to its economic roles, neoliberal educational reform has deeply authoritarian tendencies that are incompatible with democracy” (2010, p. 25). As I outline neoliberalism’s influences on education, I will demonstrate its destructive effects on the schooling process by critiquing the ethics of such practices as they pertain to upholding the ideals of social justice and the democratic state.

In order to be clear about the terminology used to describe these multiple realities and to outline my own conceptualizations, I begin this chapter by defining the terms I will use to broaden the discussion on the virtual, identity formation, identity change, and culture. This will be done through first historicizing the concept of the virtual then moving on to clarify virtual reality, augmented reality, simulation, virtual culture, and digital online culture. This is followed by a brief summary of some important voices on identity, virtualization, and culture. The chapter closes with my own perspective on virtualization and digital online culture as well as previews of subsequent chapters.

As I proceed, I would like to situate the historical, technological, and political perspectives from which I write. As a US educator who completed my graduate studies in Los Angeles, California, writing this in the second decade of the twenty-first century, I am critically aware that my experiences are grounded in the overdeveloped, high-tech Western world. I am also aware that I am from a generation at the cusp of the digital revolution. Although I did not grow up digital, I was introduced to cyberspace as a young adult through largely neoliberal education programs designed to position the United States as a global leader in the information age. I recognize this is not the same for everyone, yet whether readers are living in virtualized environments or not, all will be touched in some way by the realities I outline here.

I would also like to recognize that unlike many past inventions such as the automobile, computer technology is still changing shape. Although the automobile had different iterations, it settled into a rather predictable product early on whereas computer technology of the digital age is in constant flux. We have moved from personal computing to cloud based computing, employing tools that are also dramatically redefining the way we use the medium ranging from the mouse (i.e., drag, point, and click mechanisms) to complete gesture control. In light of this reality, I capture the essence of this phenomenon at a given moment in time. This is not to suggest that scholars should refrain from writing or theorizing about the subject but rather readers should understand that this book is a snapshot in time designed to aid in understanding the impact of this revolution. Therefore, the issues discussed in this document may be similar or very different in the near future.

Gibson’s Cyberspace

The first signs of a developing vocabulary to describe the “virtual” was born out of a term coined in science fiction and credited to William Gibson’s 1984 novel Neuromancer (Jones, 1997; Turkle, 1997) in which he defines cyberspace to be:

Cyberspace. A consensual hallucination experienced daily by billions of legitimate operators, in every nation, by children being taught mathematical concepts . . . A graphic representation of data abstracted from the banks of every computer in the human system. Unthinkable complexity . . . Cyberspace is infinite but starts with each person who chooses to step into it; and I speak now of he who in the first place dreamed it into life.

(Gibson, [1984]2004, p. 271)

Neuromancer was published at the start of the “information revolution”—a time when the computer was being ushered into the general public’s consciousness. During the same time, the Macintosh computer, dubbed the “people’s computer,” was introduced, just one year after the release of Microsoft’s Windows software. We also saw continuous improvement to the ARPANET (the precursor to the Internet), which was still limited to specialized communities within the United States, such as scientists, selected departments within universities, and the military. These technological gains were beginning to seep into the larger cultural landscape and Gibson was one of the first to articulate the next step.

Thirty years later, the concept of cyberspace no longer lives within the imagination of science fiction writers and readers nor is it limited to specialized communities, rather it is a fundamental part of our everyday lives. Every time users log on, open, or plug into Internet enabled devices they are entering cyberspace. Gibson’s most salient points are cyberspace’s “unthinkable complexity” and “infinite” dimension. Before exploring these terms, I want to mention an important element missing from Gibson’s definition.

There is a side to cyberspace that goes hand in hand with stepping into the “consensual hallucination.” This includes the equipment we use to login and navigate, the infrastructure that enables us to join, and the software, including the graphic user interface, that so often mediates the entire process. These tools are intentionally designed to be in sync with how we think, how we train our bodies to navigate them (e.g., the mouse, drop down menus), and how they ultimately influence our experiences (J.J. Gibson [1979] 1986; Norman, 1988). Working in conjunction with our visual and psychological cyberspace environments, they too impact who we are becoming. This is especially true of the next hardware iterations intended to help users function simultaneously and seamlessly in both the virtual and the real such as Google Glass and Oculus Rift, a virtual reality headset.

Gibson’s notion of complexity is evident in cyberspace’s exponential expansion. Take a moment to consider multiuser domains. In the 1980s, these were text based cyber environments (e.g., MOOS and MUDS, both refer to a form of multiuser domains) where participants interacted using avatars constructed via text. Now envision today’s multiuser domains such as Second Life and World of Warcraft, where interactions are visually complex, real time mash ups. This point is particularly interesting because today’s users are able to absorb these sophisticated systems without a steep learning curve. The expanding area of design tailored to user intuition discussed in chapter 3 provides further insight on this subject.

For Gibson, cyberspace is infinite in that its nature is analogous to space exploration where the canvas appears to be never ending. Users quickly learn that it is almost impossible to fully explore the depth and breadth of information and communities available. Especially noteworthy is that in a world defined and made predictable by boundaries, users seem to accept cyberspace as a new frontier: a modern day open prairie of the Wild West. In fact, some pour their hopes into this new environment the same way the pioneers were looking to the prairies as a representation of their hopes for a better life. Thus, cyberspace, also known as the Internet and the World Wide Web, is an environment defined by the nature of its essence, a pure communication world devoid of clear boundaries. It is also the vehicle by which we enter a state of psychological immersion. Psychological immersion happens when we are intellectually and emotionally transported to another environment that often exists in cyberspace but is not limited to it. A video game player can be fully immersed into an online multiplayer game or can be immersed in an offline game played against the computer. In both cases, the gamer is psychologically immersed while still being present in an RL environment. This reality of today is rapidly morphing into a different state of being where the two worlds cohabitate, a new high-tech existence where the early twenty-first-century concept of RL is disrupted.

The Abstraction of Realities

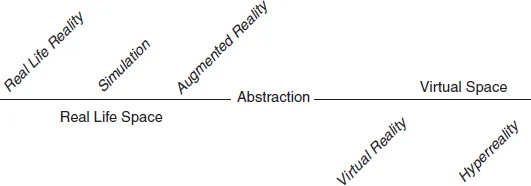

The notion of abstraction is at the heart of the distinction among terms. Gibson argues that cyberspace encompasses “a graphic representation of data abstracted.” Today, the differences among RL reality, simulation, augmented reality, virtual reality, virtualization, and hyperreality lies in levels of abstraction beginning with the real and extending to the hyperreal. The further we are detached from references to RL, the more undefined things become and the more we function in the psychological state of the virtual. This idea is illustrated in figure 1.1. The continuum represents a graduated state moving from least abstract (RL reality) to most abstract (hyperreality). Abstraction is used here to describe the non-physical qualities of technological immersion. Real life space refers to the physical world including the physicality of the Internet mentioned earlier, whereas virtual space refers to technology enabled psychological immersion such as cyberspace and offline gaming. To better illustrate the nuances, I will briefly explain each term.

Figure 1.1 Early twenty-first-century realities.

Real Life Reality

Real life reality is life experienced without computer representation, when users are not plugged into, logged on, or directly interfacing with technology. It may be influenced by technological immersion as in the case of changed perspectives or newly built relationships, but it refers to what is happening in the tangible world. It also refers to the powered off physical devices, hardware, and infrastructure that enable cyberspace entry and level of participation.

Simulation

Simulation is computer imagery that mirrors the real world, striving to directly copy the real. It often presents an idealized representation of the real or a simulacrum of it. This is seen in flight simulators, virtual tours, and computer games. Simulation can also be a combination of the real and its simulation such as in the case of many smartphone applications. The popular application called Waze, for instance, provides a simulated view of traffic patterns, while simultaneously incorporating real time data feeds from actual drivers, which appear as simulated vehicles. Users can then navigate their real world using a social, real time, virtual, simulated helper.

Augmented Reality

Augmented reality is a blending of physical reality with virtual reality: A presentation of RL augmented by virtual elements such as graphics, objects, or text. It includes aspects of simulation in that augmented things mimic the real. Although simulation and augmented reality utilize computer imagery, they still reside in RL space because they directly reference and rely upon the real.

Augmented reality is cyberspace enabled and can be controlled by gestures; “it sometimes uses facial recognition; and is often in three dimensions” (Britten, 2011). Retailers are now using augmented reality to allow customers to virtually try on clothes, and fashion shows are being augmented with a mix of RL models and augmented reality models who share the catwalk (Britten, 2011). Additionally, smartphone and tablet computer applications allow users to overlay what they see in real time with digital photos, video or text. Augmented reality is also revolutionizing tourism in the form of hardware and smartphone applications that allow museum visitors to make otherwise static content come to life leading to an interactive, dynamic and interesting adventure. Augmented reality browsers allow travelers to identify a city’s most important and interesting points of interest and learn more about their general surroundings. Furthermore, they can reconstruct historical sites by pointing their smartphone toward the original location. This is currently the case with the former Berlin Wall where augmented reality users are able to see its virtual representation as a realistic 3D model by simply pointing their smartphone at its former location (Augmented Reality in Tourism, 2014).

Virtual Reality

Virtual reality represents a shift away from referencing RL. It is a state that begins to function independent from the real, where abstraction is the norm. This is a space where users enter and build, or join, new environments, often from scratch with their own rules. Although there continues to be allusions to RL, these can be more implicit such as the way we communicate and interact within this created world. It occurs within cyberspace resulting in an environment defined by the user so that the physical rules of the “real” do not apply. For example, a player of the video game series Elder Scrolls can create a nonhuman avatar and accrue special powers not possible in the real world. Thus, virtual reality more easily crosses over into what postmodern theorists like Baudrillard have dubbed hyperreality (1994).

As Howard Rheingold describes, “Virtual Reality (VR) is also a simulator, but instead of looking at a flat, two-dimensional screen and operating a joystick, the person who experiences VR is surrounded by a three dimensional computer-generated representation, and is able to move around in the virtual world and see it from different angels, to reach into it, grab it, and reshape it” (Virtual reality, 1991, p. 17). For Rob Shields, “The virtual tricks the mind and body into feeling transported elsewhere . . . virtual worlds make present what is both absent and imaginary” (The virtual, 2003, p. 11). The film Disclosure (Crichton & Levinson, 1994) provides a window into how, at the time, technologists were projecting the evolution of cyberspace to include virtual reality through physical body attachments that enable one to project the self into a cyberworld. Today, such attachments still exist and are used in career-technical education, the military, and video gaming (VanHampton, 2012; Wingfield, 2013). Oculus Rift provides a glimpse into the next generation of virtual reality technology, a world where users are seamlessly and effortlessly immersed into virtual reality through what will soon become inconspicuous and wearable or even embedded electronics. As described by Wired Magazine, “by combining stereoscopic 3-D, 360-degree visuals, and a wide field of view . . . it [Oculus] hacks your visual cortex. As far as your brain is concerned, there’s no difference between experiencing something on the Rift and experiencing it in the real world” (Rubin, 2014). However, the term “virtual” is more commonly used to describe half-immersive experiences where there is an amount of interactivity such as with a mouse or game controller combined with a visual experience that includes user navigated three-dimensional spaces such as in video games and Google earth.

The term “virtual” has also been used in computer jargon to refer to situations that were substitutes for something else. Mark Poster, the University of California Irvine professor of Media Studies and History used the following example to illustrate this point, “virtual memory means the use of a section of a hard disk to act as something else, in this case, random access memory” (2006, p. 538). For Poster, virtual reality “is a more dangerous concept because it suggests that reality may be multiple or take many forms” (p. 538). In other words Poster notes, “modifying the word ‘reality’ to introduce another type...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 Virtualization and Digital Online Culture

- 2 A Case Study: Sherry Turkle and the Psychological Role of Computers

- 3 Down the Rabbit Hole: Identity and Societal Mutation

- 4 Manufactured Consciousness and Social Domination

- 5 Virtualization and Neoliberal Restructuring of Education

- 6 Toward a Critical Theory of Technology for Schooling

- Notes

- References

- Index